│By Dr Lucy Dow, Gale Content Researcher│

The recently published State Papers Online Colonial: Asia, Part I: Far East, Hong Kong, and Wei-Hai-Wei spans over four hundred years of British Colonial Office files, from the 1550s to 1970s. Britain’s colonial rule in Asia took various forms through the period and within different territories, with varying degrees of control, from local autonomy apart from defence and foreign relations, to full British administration. While some local people benefited from their involvement with the British, many colonised peoples suffered and resented colonial rule. This resentment led to resistance to British colonial authority, in various ways and to differing extents from territory to territory.

In the twentieth century, and particularly following the complete failure of the British to protect the local communities from Japanese invasion during the Second World War, the cumulative effect of this resistance, combined with other geopolitical factors, led to the rapid reduction in the size of British Empire, as former colonies secured their independence in what is now referred to as the period of decolonisation. The primary sources in this online archive document this change in the political landscape of Asia and Britain, as explored in the examples below.

The British Empire in a Changing Geopolitical Landscape: The Malayan Emergency, 1948-1960

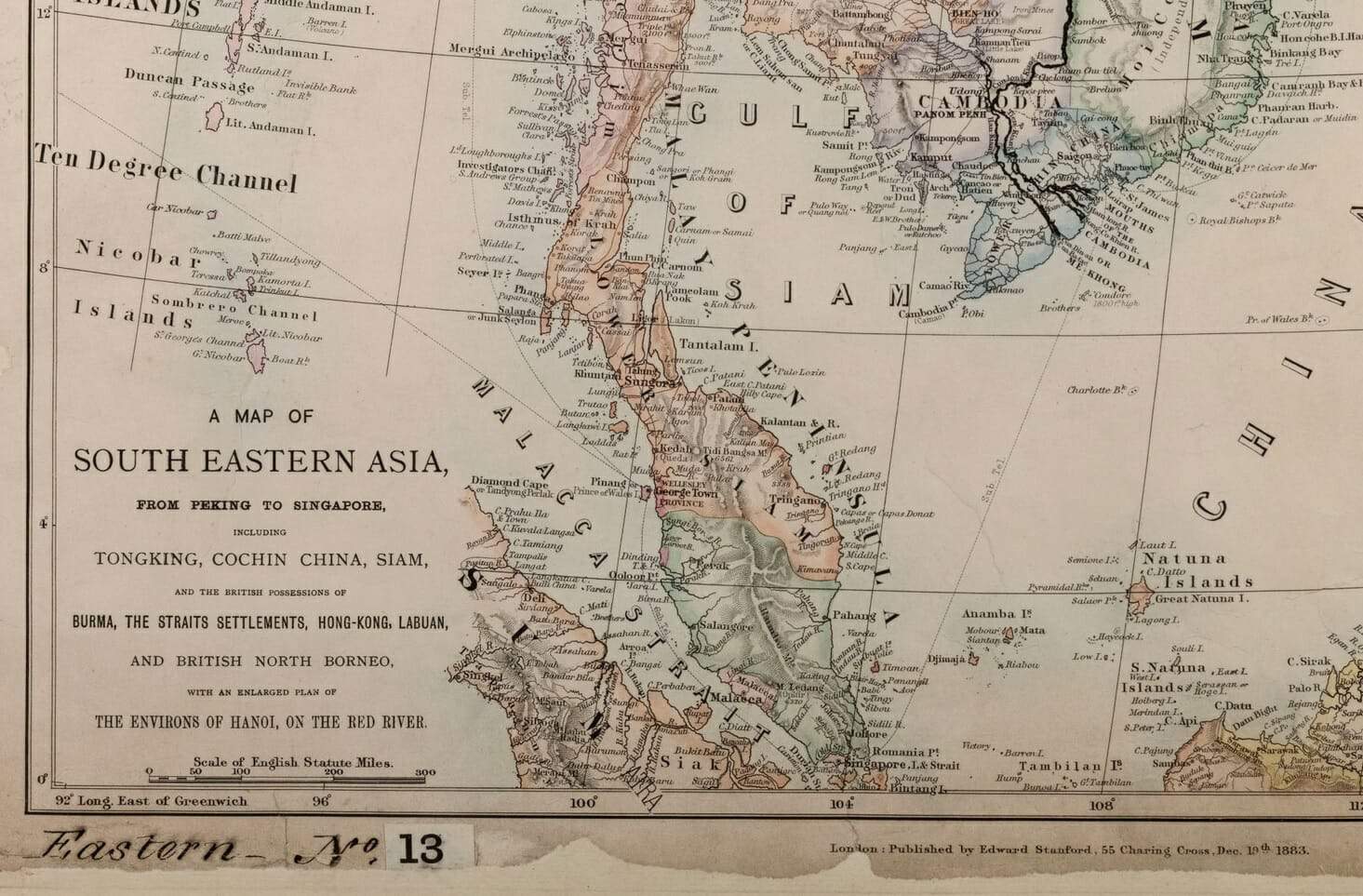

An instructive example of how we can use State Papers Online Colonial: Asia, Part I to explore decolonisation in Asia is by looking at documents related to The Malayan Emergency, 1948-1960. The Malayan Emergency refers to a period of emergency rule instigated by the British colonial authorities in what is now Malaysia from 1948-1960. There had been a British colonial presence in this part of Asia since the late eighteenth century. This ended with the Japanese invasion and occupation of Malaya and surrounding areas during the Second World War.

The Japanese occupation was resisted by a range of local communist guerrillas, and gave further impetus to the Malay, and other, nationalist movements. Following the defeat of the Empire of Japan by Allied forces, the British colonial administration set up the Malaya Union in 1946, combining the Federated Malay States, Unfederated Malay States and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca under one administration, after obtaining the agreement of the Malay State rulers. However, for several reasons, this was resisted by the ethnic Malay population leading to the dissolution of the Malayan Union, and its replacement by the Federation of Malaya in 1948.

In the document below, part of a selection of documents supplied by the British government as part of their attempt to gain funding for the Federation of Malaya from the USA in 1950, the author (a British colonial official) outlines their understanding of the reasons for the uprising. A key factor, in the author’s estimation, is the influence of a wider communist groups in Asia, specifically India and China:

The relationship between anti-imperialist movements and the wider communist movement highlights the extent to which anti-colonial resistance within the British Empire was often inextricably linked to the Cold War. British colonial officials had to react to this changing geopolitical landscape, as the reference to ‘Korea and Indo-China’ in the above extract demonstrates.

Part of the British colonial response to the communist-led insurgency in this period was to implement The Briggs Plan, a forced resettlement plan in which rural workers, mainly of Chinese descent, were made to live in “new villages” with the aim of separating communist guerrillas from the local working population. The report above explains that the rural workers ‘concentration in resettlement areas enables them to be given protection against intimidation by the [communist] bandits which is impossible so long as they are scattered all over the countryside’.

In order to provide this “protection” the report explains that new roads, police stations and police posts are required. The author argues that, ‘Unless these measures are taken and the new settlement of villages are protected by the construction of a strong barbed wire fence, with an adequate police guard, there can be no hope of preventing contact between these categories of the population and the bandits, and the giving of aid both in the form of food, money and information by the former to the latter’. Thus, whilst The Briggs Plan is initially presented as designed to protect the rural population, from this explanation it is clear that what were effectively being created were concentration camps aimed at undermining the support these rural populations provided to communist, anti-imperialist guerrillas.

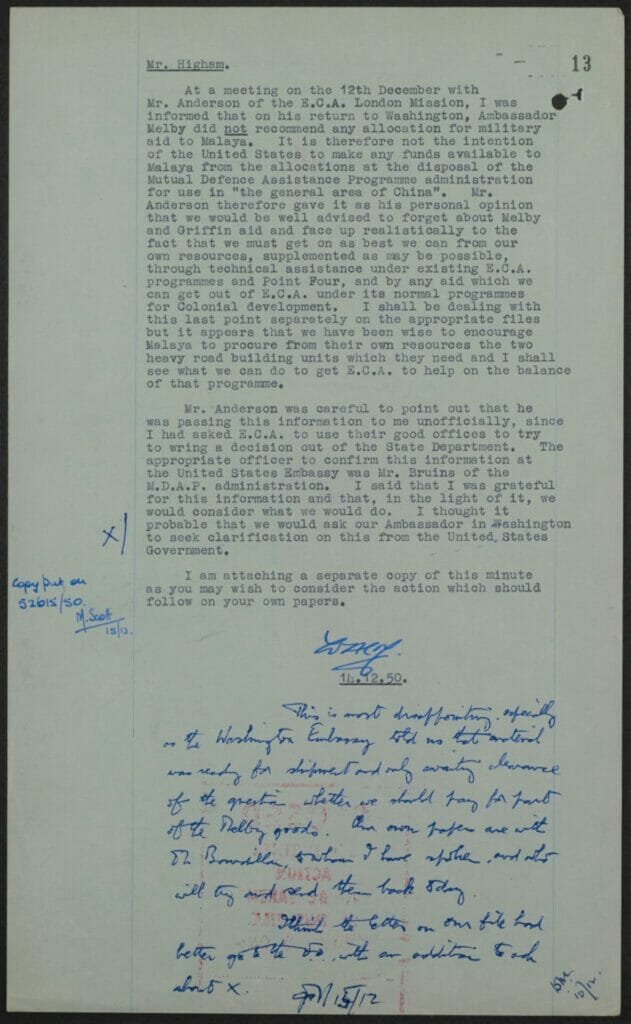

We can see then, in this one report, how the combination of a changing broader geopolitical landscape and growing local resistance in the British Empire put pressure on colonial resources. The wider set of documents which this report is part of highlights how the British government, in the wake of the Second World War, was not able to meet these pressures and provide the required resources. As this letter below, dated December 7, 1950 from the Colonial Office, reveals, the Federation of Malaysia was keen to access funds from the USA to help build roads as part of their anti-communist, counter-insurgency efforts.

![The Griffin Mission' (1950) [manuscript] Records of the British Colonial Office CO 537/6617](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/SPOCF0001-C00005-M0000729-00190-840x1024.jpg)

However, the US government was not sufficiently concerned with the situation in Malaya, compared to other parts of Asia, to provide the British government with assistance, as this document from December 14, 1950 reveals:

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/TEYTLK414336979/SPOC?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-SPOC&xid=009536c7 (image 15)

That the British government had to appeal to the USA for funds highlights the extent to which Britain, having been financially depleted by the Second World War, was unable to fund colonial defence by this period. Popular, anti-imperialist insurgencies pushed the British Empire to breaking point. The US, now the more dominant global economic and military power and already financially supporting the UK and Western Europe through the Marshall Plan, chose to focus on different Cold War priorities (specifically Korea and Vietnam). It was this combination of factors, documented in this folder of primary source materials in State Papers Online Colonial: Asia, Part I, which paved the way for the decolonisation of Malaya.

The British Empire in All but Name: The Mid-Twentieth Century Commonwealth, Singapore and Global Decolonisation

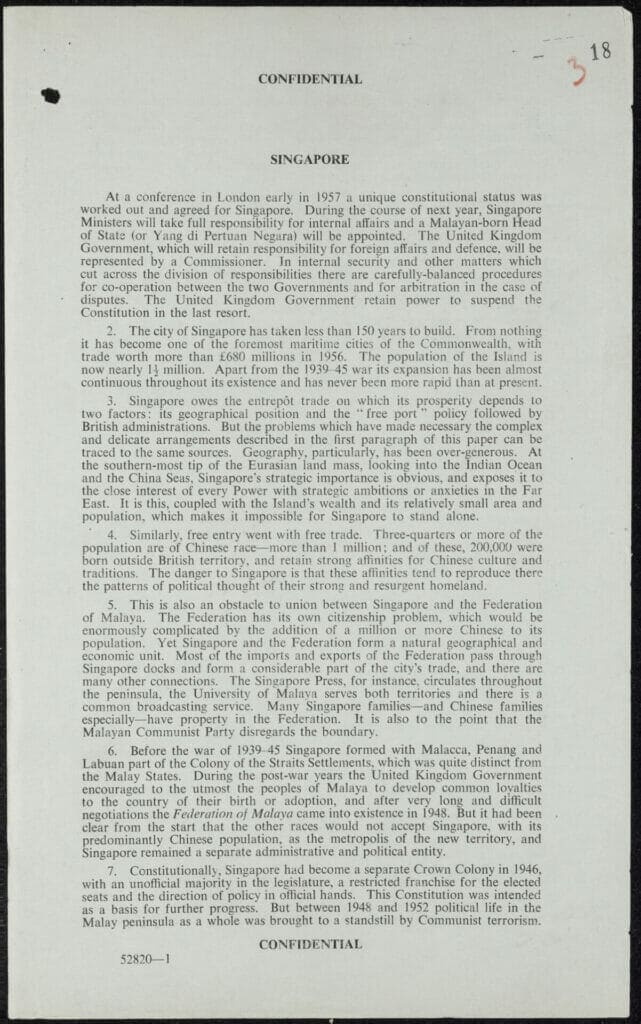

Parts of what would become Malaya were part of a region of Asia referred to by the British as the Straits Settlement. Central to the Straits Settlement was the island that would come to be known as Singapore. In 1946, Singapore became a Crown Colony, a form of self-governing colony. Political unrest in Singapore in the 1950s, in part related to the Malayan Emergency, led to ‘a unique constitutional status’ being created for Singapore in 1957. The seemingly successful negotiation of Singapore’s place within the Commonwealth led the Commonwealth Relations Office to ask the Far Eastern Department of the Colonial Office to compose this ‘Colonial Appreciation’ document which outlined the recent history of Singapore and its new constitutional status:

As this document outlines, this new constitutional status involved some internal affairs being dealt with by Singaporean ministers, but external affairs remaining the responsibility of the United Kingdom, and the United Kingdom government retaining the ability to suspend the Constitution. The relationship between Singapore and the United Kingdom this new constitutional status created reveals much about the partial and piecemeal nature of decolonisation in the British Empire. It also highlights the ways in which the British government sought to use the Commonwealth as a way of maintaining a version of imperial power.

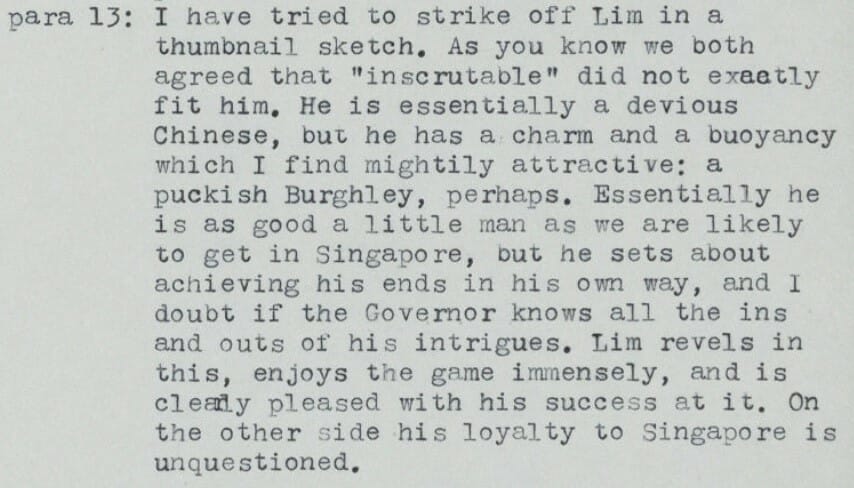

The highly racialised basis for British ideas about the nature and function of the Commonwealth in the mid-twentieth century is revealed in the accompanying correspondence between British government ministers, colonial administrators and civil servants in this file. In a set of comments on a draft of the “Appreciation” written by the British official John Hennings and dated October 22, 1957, Hennings describes Lim Yew Hock (a key figure in Singaporean politics at this time) as “essentially a devious Chinese” but “as good a little man as we are likely to get in Singapore”.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/FBXJFZ119059619/SPOC?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-SPOC&xid=e39e0a40 (image 5)

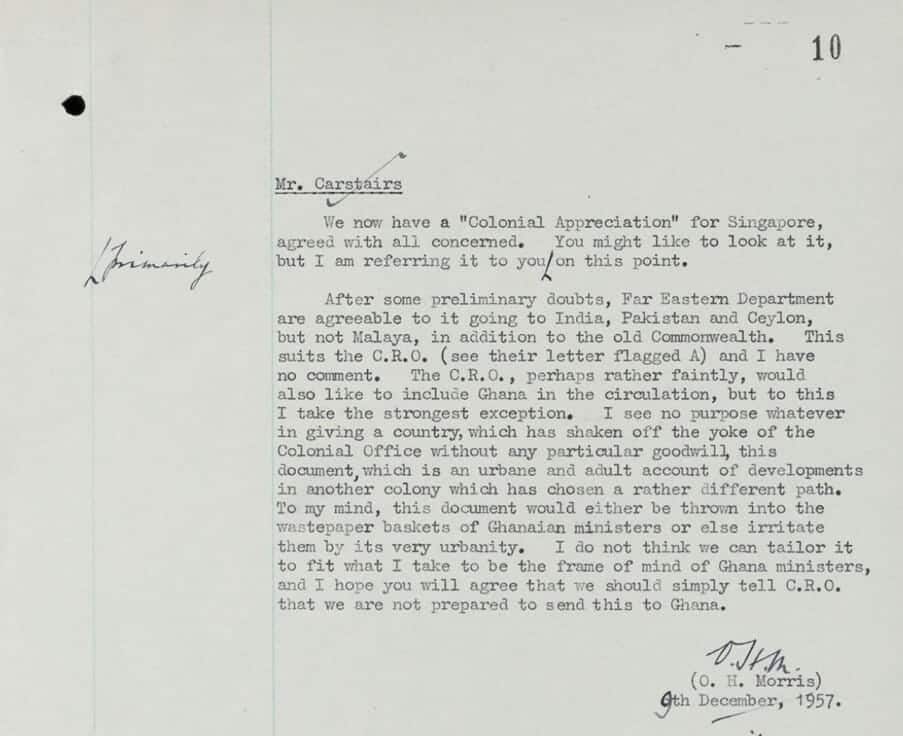

The British government’s intentions for the Commonwealth, and attitudes towards decolonisation, did not go unnoticed by newly independent states. In the discussion of the circulation of this document, another British official, O.H. Morris, in somewhat terse and patronising terms, opposes the document being sent to the Ghanian government.

Ghana had gained independence from Britain in March 1957, led by the anti-colonial thinker and activist Kwame Nkrumah. Nkrumah (and by extension Ghana’s) role in this period as an advocate for African and Asian liberation more generally made him highly critical of all the European imperial powers and particularly the British. British government officials were well aware of this situation. In this note from November 1, 1957 the then head of the Far East Department, Walter Ian James Wallace, recommends the production of two copies of the Singapore “Colonial Appreciation” – one for ministers in the UK and ‘”old” Commonwealth countries” and one ‘”angled” specifically for “anti-colonials”’ in the ‘new Commonwealth’.

!['Political Situation in Territories of Colonies on Gaining Independence' (1957) [manuscript]](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Picture3.jpg)

The Singapore ‘Colonial Appreciation’ document and the wider folder of correspondence that accompanies it in State Papers Online Colonial: Asia, Part I highlights how this archive allows for the investigation not only of specific regional decolonisation histories in Asia, but also the wider geopolitical impact of the process of decolonisation. As these documents illuminate, the changing nature of the Commonwealth in the post-Second World War era, with the ascension of newly independent African and Asian states, gave it a different function for the British government. The primary source materials in State Papers Online Colonial: Asia, Part I reveal the continuities between the British Empire and the Commonwealth, as well as the resistance to this new form of imperial power amongst anti-colonial leaders.

If you enjoyed reading about some of the fascinating documents researchers can find in State Papers Online Colonial, you may like:

- Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories

- The Rise and Fall of Chinese Indentured Labour

- Asia, as Recorded in British Colonial Office Files

- The History of Extradition in Hong Kong

- Who is the Founder of Modern Singapore?

- Dr Wu Lien Teh as a Travelogue Writer

- Tears, Cheers, The Archers, and Soy Sauce: The Hong Kong Handover of 1997

- Early Twentieth-Century Explorers in Inland Asia

- Ngiam Tong-Fatt’s Essays Provide Great Insight into Mid-Twentieth Century Southeast Asia

- Uncovering the History of Twentieth-Century Hong Kong, China, and the World

Blog post cover image citation: Map of South-Eastern Asia from Peking to Singapore …. 1883. MS Records of the British Colonial Office CO 700/EASTERN 13. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). State Papers Online Colonial, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/RVSSYX488061435/SPOC?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-SPOC&xid=ff36f9cf&pg=2