│By Holly Kybett Smith, Gale Ambassador at the University of Portsmouth│

The late eighteenth century was a turbulent time for those in power. Across Europe, monarchies were clinging to their authority by threads: the American Revolution saw British imperial rule challenged, and in France, Louis XVI was unseated from his throne, putting an end to the Ancien Régime. Simultaneously, as the French people rebelled against their absolute monarch at home, the Haitian Revolution saw self-liberated slaves free themselves from French colonial rule. Everything, everywhere, was in flux. With all of this in mind, it’s no surprise that the spirit of the era formed the crucible for the birth of the Gothic literary genre.

When discussing the Gothic in academic circles, we tend to ascribe the origins of the genre to one particular work: The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole, published in 1764. This is because Walpole himself described his tale as “Gothic” – the first noted use of this term to describe a piece of literature, as opposed to an architectural style. But one novel does not make a genre, and as the eighteenth century marched into the nineteenth, Gothic literature grew to encompass new components, stretching itself into the shape we recognise today. For more information on the Gothic as it evolved into contemporary horror, take a look at this blog post by my fellow Gale Ambassador, India Marriott.

In this blog post, meanwhile, I’m going to examine the emergence of early Gothic literature as it began to appear at the start of the nineteenth century – and explore how we can study this using Gale Primary Sources.

The Spectre of Robespierre

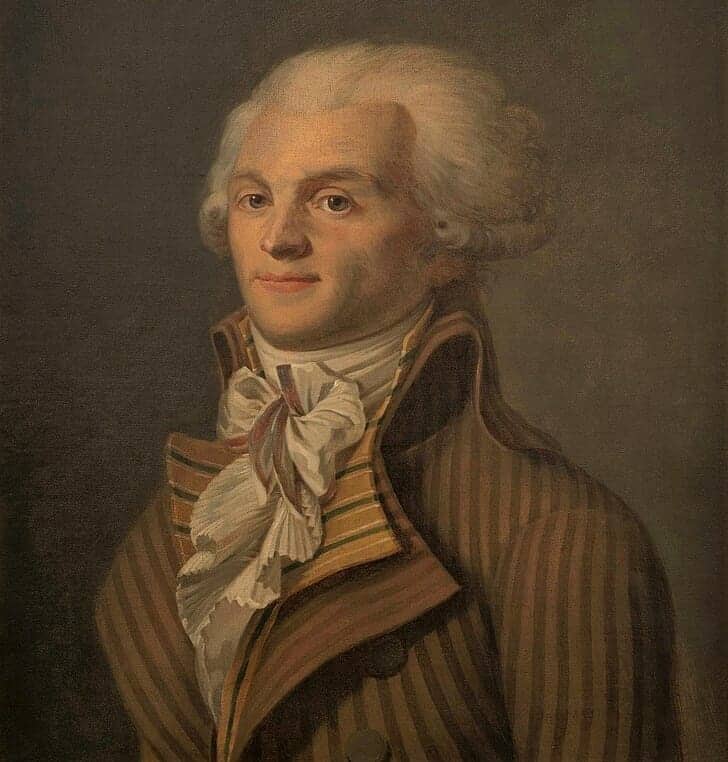

The most well-known of the revolutionaries, Maximilien Robespierre’s name – to this day – calls to mind gruesome beheadings and bloodshed. While recent scholarship, by writers such as Ruth Scurr and Peter McPhee, has sought to re-introduce nuance into conversations about this controversial figure, there remains an undeniable dark stain over his name: a stain spread and cemented by early nineteenth-century propagandists seeking to quell future attempts at revolution in Europe.

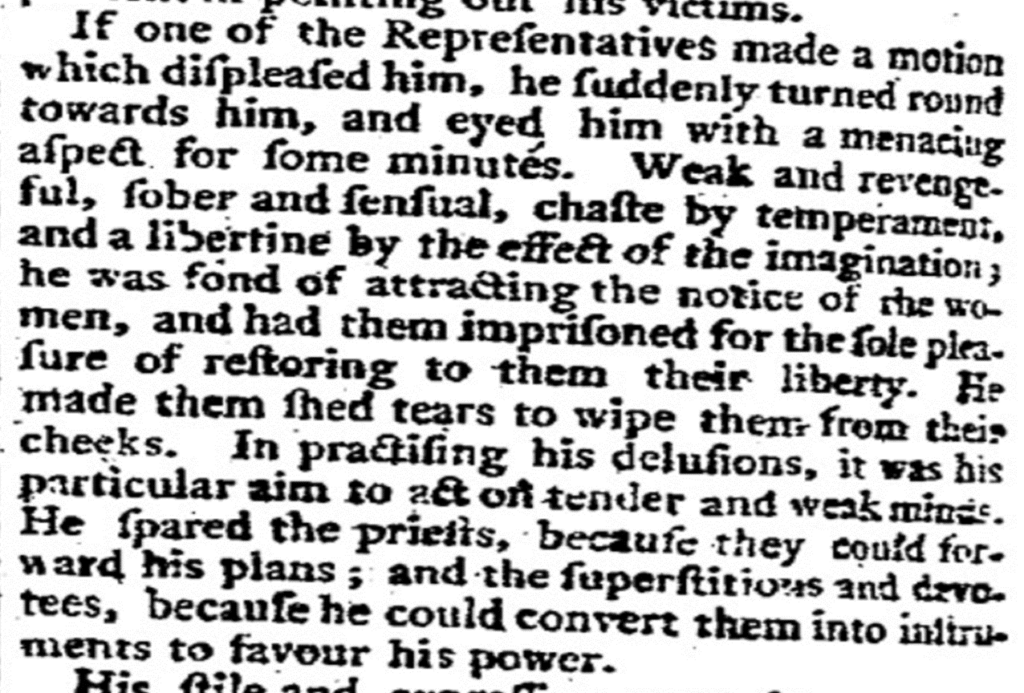

We can find an example of this in the article below, published in The Times in August 1794 – a month after Robespierre’s death – which I accessed via The Times Digital Archive. Its description paints Robespierre as a calculated manipulator, who “made [women] shed tears to wipe them from their cheeks.”

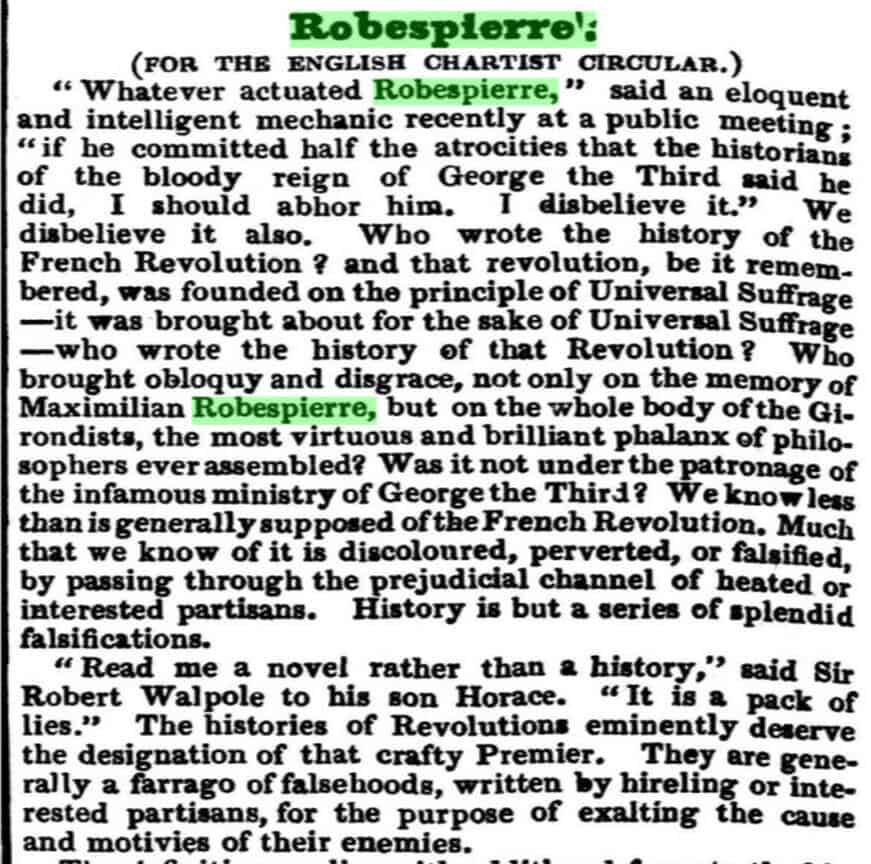

Many primary sources, and early secondary sources, on the Revolution and its international impact can be found using Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online – though you may need to translate some of it from French. These early sources can be incredibly hard to track down elsewhere, making ECCO an invaluable resource. You can also find a large number of documents discussing Robespierre into the nineteenth century in Gale’s Nineteenth Century Collections Online. For example, this periodical piece decrying the waves of propaganda that rose up in the wake of the Revolution:

But what – you may ask – does Robespierre have to do with the Gothic?

Whether you believe the anti-Robespierrist propaganda to contain a grain of truth, or – like the author of the above article – to be “a farrago of falsehoods”, there is no denying that Robespierre’s depictions in this propaganda are ghoulish; that he is presented as something sinister and less-than-human. One could consider these hit-pieces an early exercise in horror writing. Given that this was the period when the Gothic genre was finding its legs, it may be possible to draw connections between the two – to find traces of Robespierre’s exaggerated ghost in the turn-of-the-century Gothic imagination.

The Modern Prometheus and Beyond

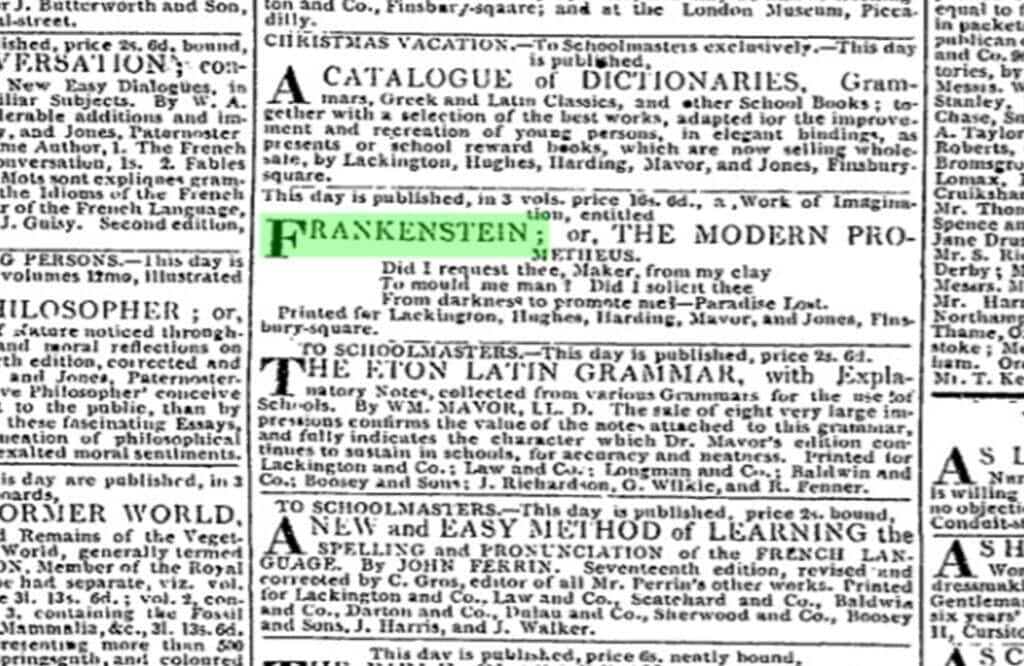

In 1816, Mary Shelley sat down in the Villa Diodati to pen Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus. Two years later, its publication was announced in the Times, as can be seen in the source below.This debut novel would become one of the most famous staples of nineteenth-century Gothic literature, influencing many Gothic writers and scholars to come. Its influence prevails to this day.

Gale’s Nineteenth Century Collections Online and British Library Newspapers archive host a number of book reviews, both of Frankenstein and other Gothic texts which may have taken inspiration from Shelley, and these are a fascinating insight into the reception of the novel in its time. They are easy to search for using ‘Frankenstein’ as a keyword, and can be filtered by date of publication in order to focus in on particular decades.

By the Victorian era, Gothic literature and its conventions were well-established in the British literary canon, and had strayed across the globe to find relevance in America, too. We see this in the works of authors like Nathaniel Hawthorne and Edgar Allan Poe. Gale also hosts an archive of Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, which might be a useful resource to use if you’d like to see how the Gothic genre developed on other continents.

It’s also well worth checking out Gale Literature for literary criticism and biographical resources, if your library has access to this database. Type the names of the database into in your library catalogue to check!

If you enjoyed reading about the Gothic genre in the early nineteenth century, and you’re interested in learning more about the Gothic genre or nineteenth-century history, check out:

- From Grimm to Gothic: The Evolution of the Horror Genre

- The Evolution of Monstrosity from the Nineteenth Century to the Present Day

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- How Ancient Egypt was Presented in Nineteenth Century Newspapers

- Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld – A Great Arctic Explorer of the Nineteenth Century

Blog post cover image citation: Eltz Castle, Wierschem, Germany during sunrise. Image by Cederic Vandenberghe on Unsplash.com.