│By Phoebe Sleeman, Gale Ambassador at Durham University│

Photographs are something we all now regularly take for granted. I have already taken a multitude of pictures today – some carefully crafted, others on the spur of the moment. What does this seemingly mundane and ordinary act of photographing bring to a study of history, and why should photographs be included within archives?

Photographs are not normative written sources which leads some to be sceptical of their historical value. Others assert that photographs contain less historical bias as they show the reality of what occurred in the past. Neither of these attitudes are helpful. Instead, using Gale’s Picture Post Historical Archive, an example of the intersection of photography, writing and the beginning of photojournalism, I will dissect the value of ‘Photographic Histories’ as an area of study and assess the usefulness of such an archive.

A University Module on Photographic Histories

Last year I took a module at Durham University on Photographic Histories, and I was persuaded that photography and history cannot be separated. Firstly, photography allows for the circulation of history; the reproducibility and physicality of photographs acts as a tool for creating social networks. This is evident in the Picture Post where, in the first edition on October 1, 1938, the publication encouraged their readers to start saving their copies of the magazine for posterity describing how ‘At the end of twelve months you will have a complete record of the year’s events – a slice of history in vivid intelligible, entertaining form.’

Performance Within Photography

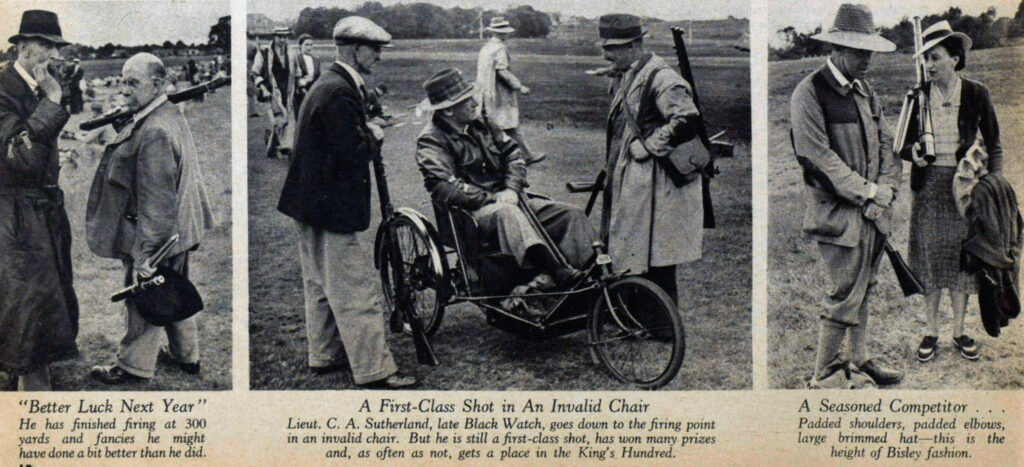

However, photography doesn’t just circulate history, it also creates history. This is what struck me the most when I was studying this module. I knew photography had a history, something which we would also study within this module, but I had never considered that photography was also a historical actor. This can be seen in the series of photographs below of the Bisley shooting competition, from July 29, 1939, also from the Picture Post Historical Archive. Despite seemingly not engaging with the camera, there is a performative element to these photographs. The composition of each suggests an awareness of the presence of a camera and a self-presentation towards the camera.

Indeed, in his article ‘Photography, history, (dis)belief’ in the journal Visual Resources, Ulrich Keller highlights how just the presence of a camera, for example within congress, turns it into a performed event.1 Photographs are often used in history school textbooks as neutral images with the idea that the camera just happened to be there, but in reality photography creates narratives that become history.

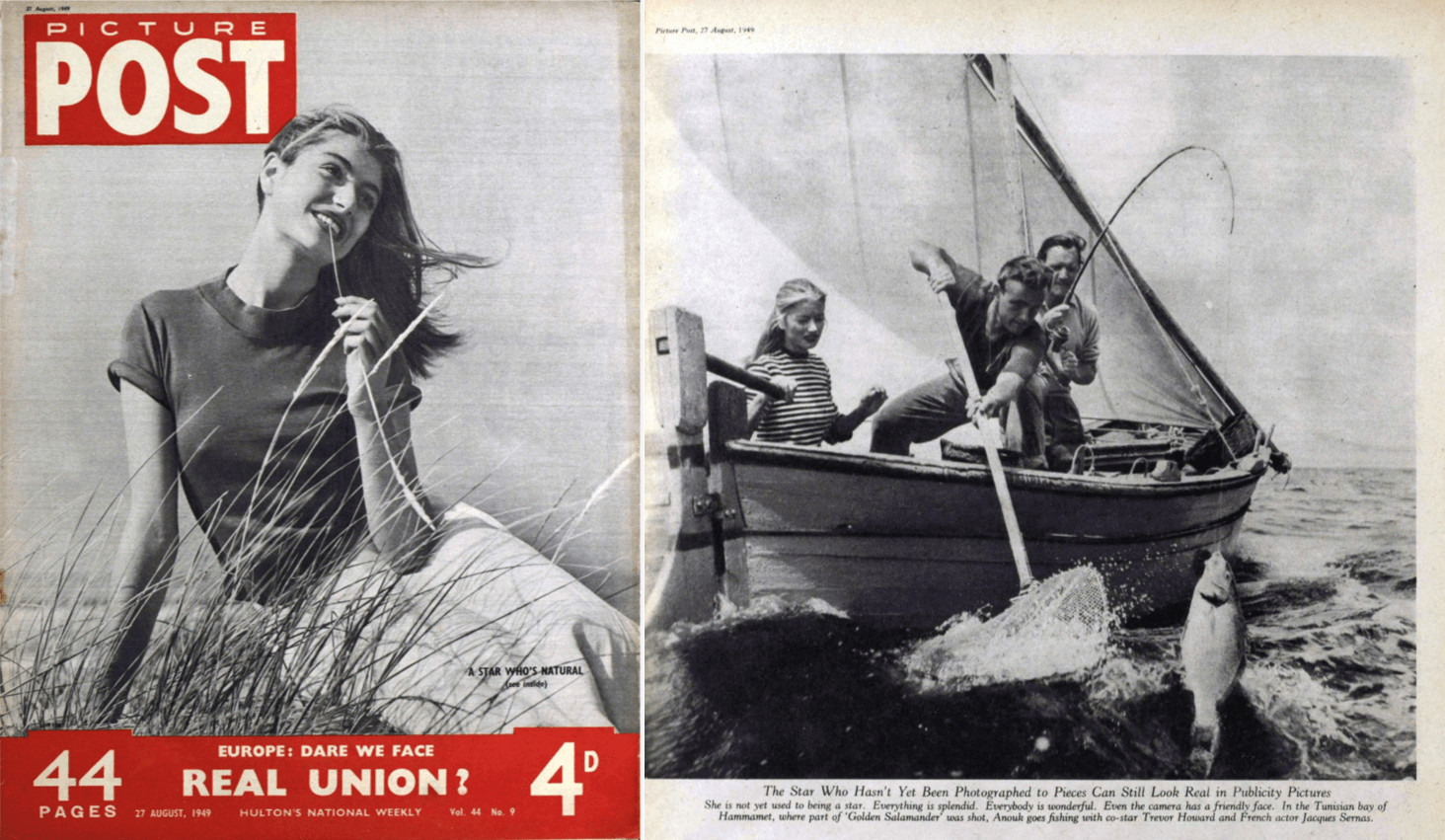

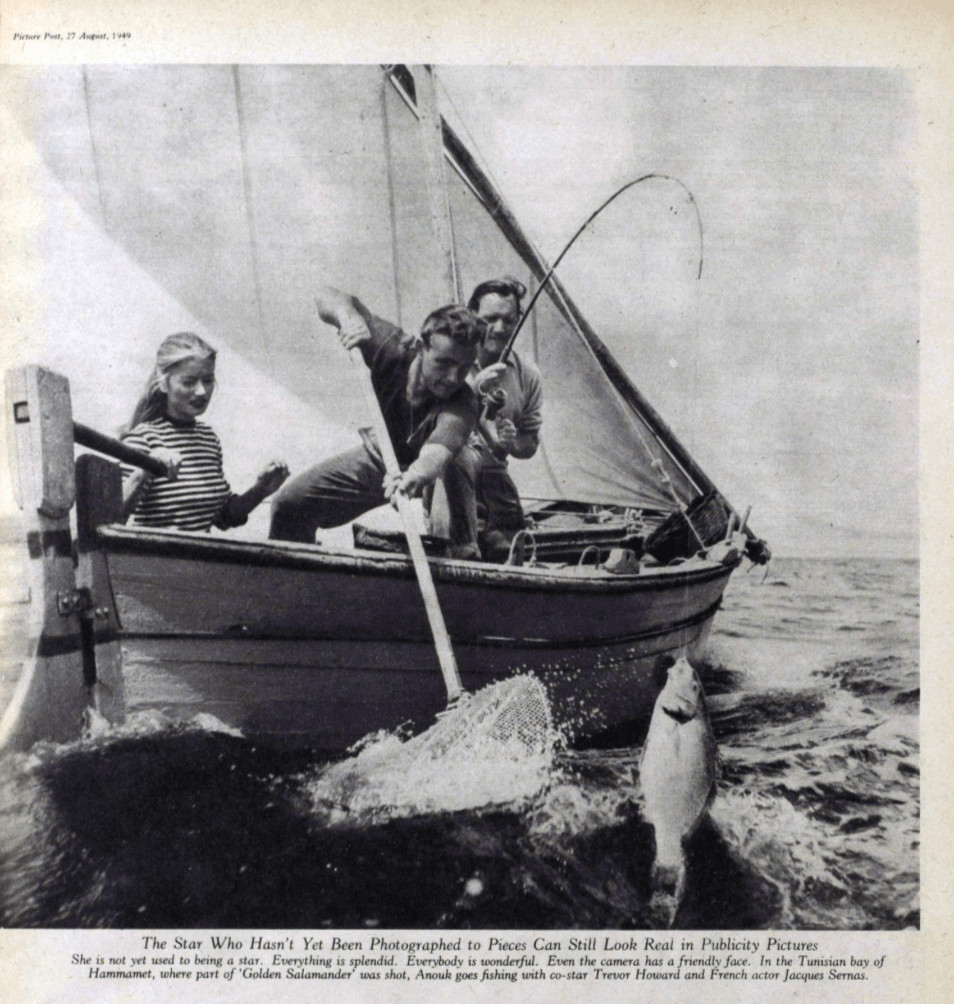

‘The Star Who Is Natural’

The August 1949 edition of the Picture Post offers an interesting take on this. This edition contains an article on ‘The Star Who is Natural.’ Having not ‘yet been photographed to pieces’, she can allegedly ‘still look real in publicity photographs.’ The Picture Post clearly sees that there is a performative element to photography and seeks to distance this actress from that performance by taking unposed pictures. The article contains a number of photographs of her: in a donkey race, falling off a donkey and going fishing. However, the very presence of a camera leads to a sense of performance, and we should look, as historians, beyond the seeming lack of performance to see the inevitable positioning within the photographs.

As this university module taught me, the emergence of photojournalism and specialised press photographers was part of a bigger cultural shift in how people place themselves in relation to the world around them. These photographs of the ‘unposed’ actress invite us to become a spectator, to imagine we are there and create a new level of consumption. The logic flows that we see it and so we experience it and so we know it. We’re supposed to forget that they are just photographs, and leave unquestioned where they came from or how they are being presented to us.

Absences Within Photography

For a historian, or indeed an anthropologist or anyone else who is seeking to understand photographs as mediated snapshots of singular points in time and space, rather than ultimate reality, the most illuminating part can be the absences within photographs. Often these absences are difficult to see and can be multi-layered. There are simplistic absences – what is going on outside the frame captured by the lens, but also more subtle absences.

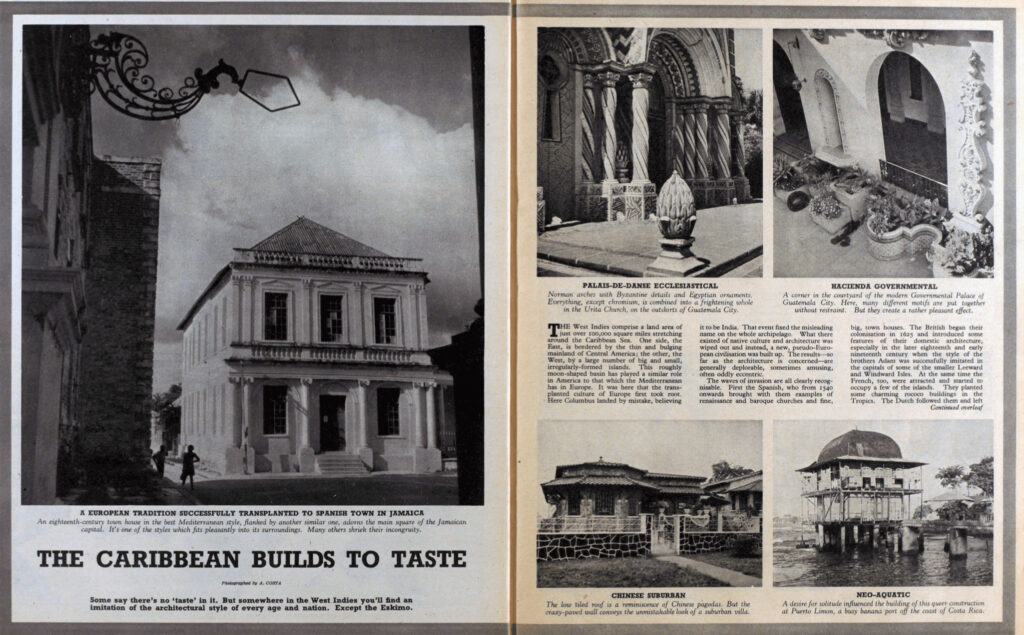

This is evident in the photographs below from the Picture Post in December 1949, of European houses built in Jamaica entitled ‘The Caribbean builds to taste.’ Except for the silhouettes of two small boys, there is an absence of people. Simply being in the Picture Post shows a European’s mediation of these images, and the absence of people, local or otherwise, further foregrounds the Eurocentrism of these photos. This absence is creating a historical narrative of Western superiority, extending into architecture, a view also conveyed by the language used in this article.

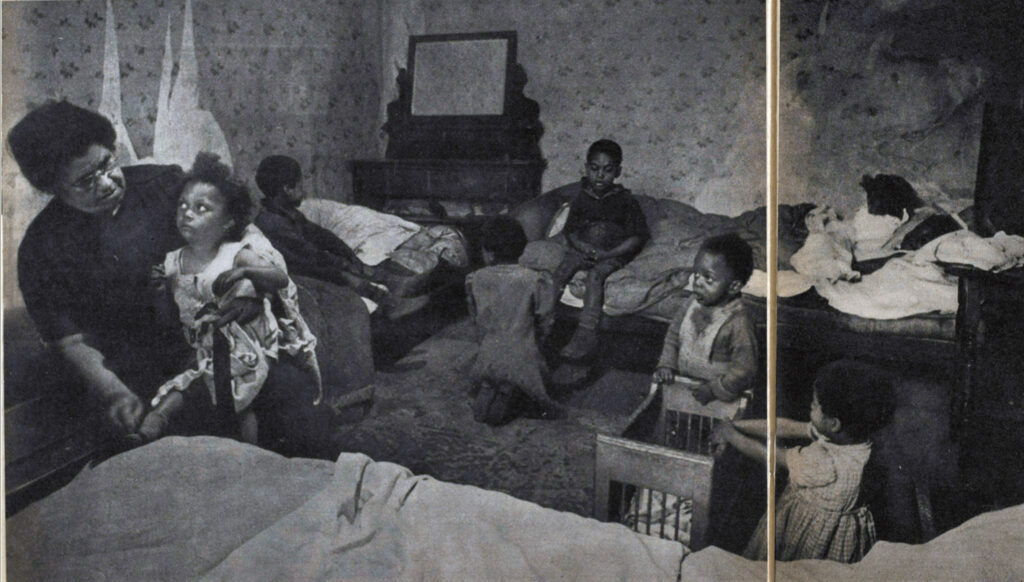

Absences can be subtler still, as seen in the photograph below from the Picture Post published in the same year as the architectural photos above. This photo is part of an article about a survey the Picture Post conducted into the work, living conditions, hopes and grievances of the ‘Colonial people who live among us’. The image is captioned ‘The overcrowding that is typical of conditions in the coloured quarters of some British towns’. The absence here is found in the lack of direct eye contact with the camera. One can hypothesise that perhaps this shows an absence of consent or a lack of desire to be photographed. Even the children are looking at the older woman, or with their backs turned. The camera is trying to force people to perform a role and the only agency they have is to turn away. It is therefore important to dwell on people’s posture towards or away from the camera, and how the presence of a camera creates a performance. This is especially true in photojournalism where the very aim of photography is to tell a narrative.

Photographs Must be Critically Analysed

Dwelling on these absences and performances doesn’t, however, take away from the value of photographs as a historical source. Photographic history is built around a critical analysis of photographs; by dissecting the elements within, one is able to learn more about the society and culture in which the photograph was created than one could from simply accepting it a historical reality.

I hope this blog has given you food for thought. Why not check out more photos yourself in Gale’s Picture Post Historical Archive? It is fascinating to dissect what historical narratives the photos are telling. Start with seeing what conclusions you can draw from the absences and performances of those pictured in ‘The World Looks at No. 10’ in the first issue of Picture Post below.

!["Picture Post." Picture Post, vol. 1, no. 1, 1 Oct. 1938, p. [1]. Picture Post Historical Archive,](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/image-5-1024x685.jpg)

If you enjoyed reading about the Picture Post Historical Archive, and the power and use of photos in newspapers try:

- From Coupons To Cocktail Dresses: Tracking Changes to Women’s Wartime Fashion Using the Picture Post

- A Reflection on the Reign of Queen Elizabeth II: The Modernisation of the Monarchy

- British Royal Babies Through the Ages

Blog post cover image citation: Design combining the following sources –

“Picture Post.” Picture Post, vol. 44, no. 9, 27 Aug. 1949, p. [1]. Picture Post Historical Archive, 1938-1957, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EL1800047798/PIPO?u=duruni&sid=bookmark-PIPO&xid=f4525233 and

“A Star who is Natural.” Picture Post, vol. 44, no. 9, 27 Aug. 1949, pp. 25+. Picture Post Historical Archive, 1938-1957, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EL1800047846/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=332cf8ff