|By Liping Yang, Publishing Manager, Digital Archive and eReference, Gale Asia|

Gale has recently released China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part II, 1865–1905. Consisting of volumes 873–1768 in the highly acclaimed FO 17 series of British foreign office files plus seven volumes of Law Officers’ reports relating to China from FO 83, Part II covers the latter half of the nineteenth century (see my first blog post about this module – Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century for the main topics covered in Part I). The complete Imperial China and the West provides a vast and significant primary source archive for researching every aspect of Chinese-Western relations from 1815 to 1905.

Here, with the help of Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR) technology, researchers will be able to conduct full-text searches across more than one million pages of manuscripts relating to the internal politics of China and Britain, their relationship, and the relationships among Britain and other Western powers—keen to benefit from the growing trading ports of the Far East—and China’s neighbours in East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Imperial China covers a wide range of topics including diplomacy and war, trade, piracy, riots and rebellions, treaty ports, Chinese emigration, and railway building. In this blog post I’ll walk you through some of the fascinating topics and themes covered in the approximately 600,000 pages of manuscripts included in Part II.

The First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895)

This war was triggered by the competition between the two East Asian empires for the control of Korea. It started in the Korea Peninsular and then spread to northern and eastern China, resulting in the defeat of the Chinese Qing Dynasty. Despatches from the British legation in Peking and consulates based in other areas affected by the war provide a good coverage of the event in terms of the evolving situation on the battleground as well as the Western powers’ responses.

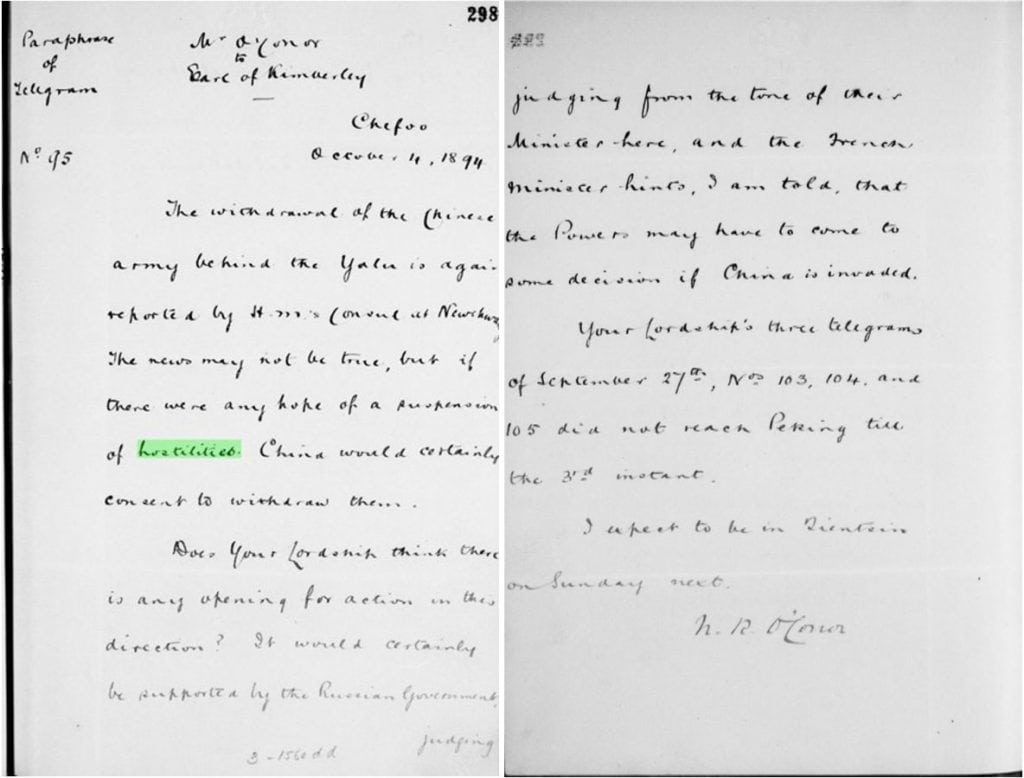

In a despatch of October 4, 1894 (paraphrase of telegram), British Minister to China Sir Nicholas Roderick O’Conor reported that the Chinese army had withdrawn behind the Yalu River – which separates China and Korea – in the hope of suspending the hostilities with Japan. The despatch also touched on the planning of the powers (especially Russia and France) to intervene if Japan would invade China.

Available on Wikimedia.

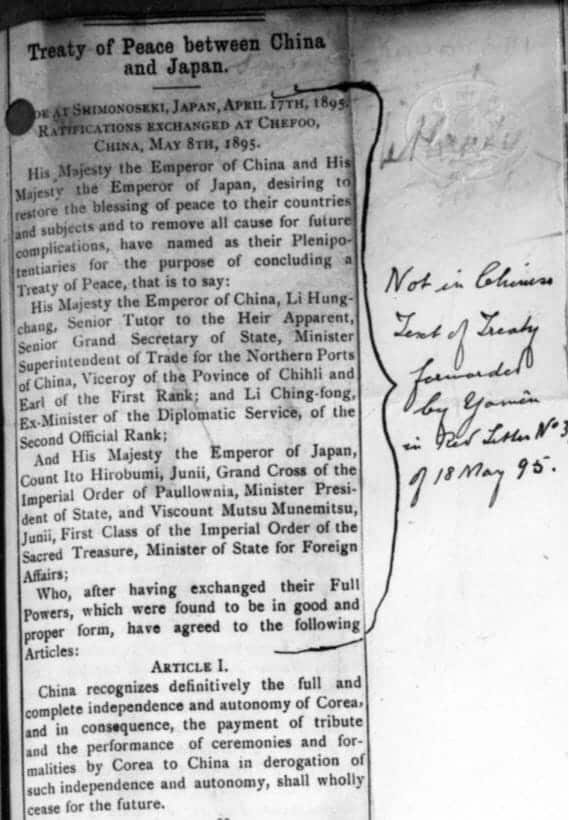

The war culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Shimonoseki (馬關條約) on April 17, 1895. In a despatch of May 20, 1895, to the foreign secretary, O’Conor enclosed the full text of the treaty in English published in the Peking and Tientsin Times, and commented that, to his disappointment, Japan had secured commercial advantages which the British had wanted but failed to obtain from China in 1869.

The Boxer Rebellion

Anti-foreign riots in China reached a peak in 1900 with the outbreak of the Boxer Rebellion that swept across many parts of northern China, including Shandong, Hebei, Tianjin, and Beijing. The movement led to the siege of the international legations in Peking, the Boxer War launched by an alliance of eight powers to relieve the siege and suppress the rebellion, and the signing of the Protocol of Peking.

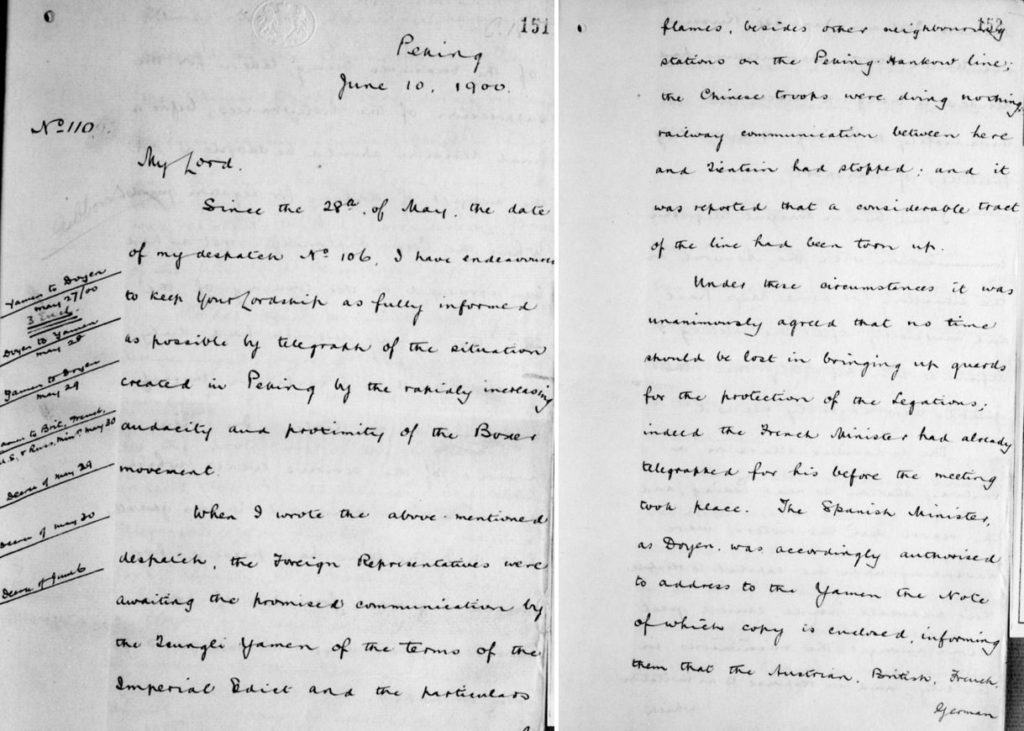

In a despatch of June 10, 1900 to Foreign Secretary Lord Salisbury, British Minister to China, Sir C. MacDonald described the deteriorating situation in Peking and surrounding areas created by the approaching Boxer movement, and the importance of bringing legation guards to protect the legation quarter in Peking. Soon afterward, the siege of the international legations started.

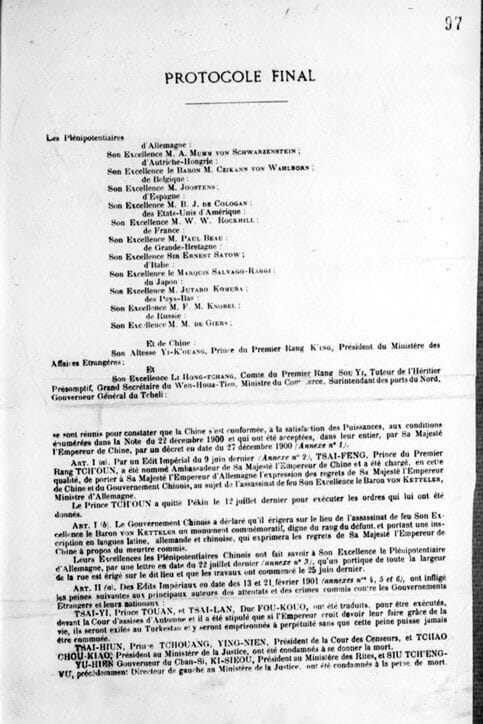

After the siege was relieved in August, the allies continued their suppression campaigns to areas surrounding Peking. At the same time, peace negotiations started with the Chinese imperial government, and these lasted till the signing of the Protocol of Peking and annexes on September 7, 1901. Below is a page extract from the full text of the Protocol as part of the enclosure to a despatch of September 12, 1901, from Sir Ernest Satow who replaced Sir C. MacDonald in October 1900 as the British Minister to China.

Relations with China’s Southern and Western Neighbours

China’s southern and western neighbours include Southeast Asian countries such as French Indochina (Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos), Siam (Thailand), and Burma, as well as India. Some of these (e.g., Thailand and Vietnam) had been China’s tributary nations for centuries before the arrival of Western powers. China’s relations with these neighbours as well as theirs with the West are covered in both parts 1 and 2 of Imperial China. Regarding Southeast Asia alone, there are about 50 volumes of files dedicated to the affairs of Burma and Siam (Vol. 1059–1065, 1094–1095, 1150–1153, 1175–1188, 1219–1226, 1265–1272, 1293–1296, and 1742–1743).

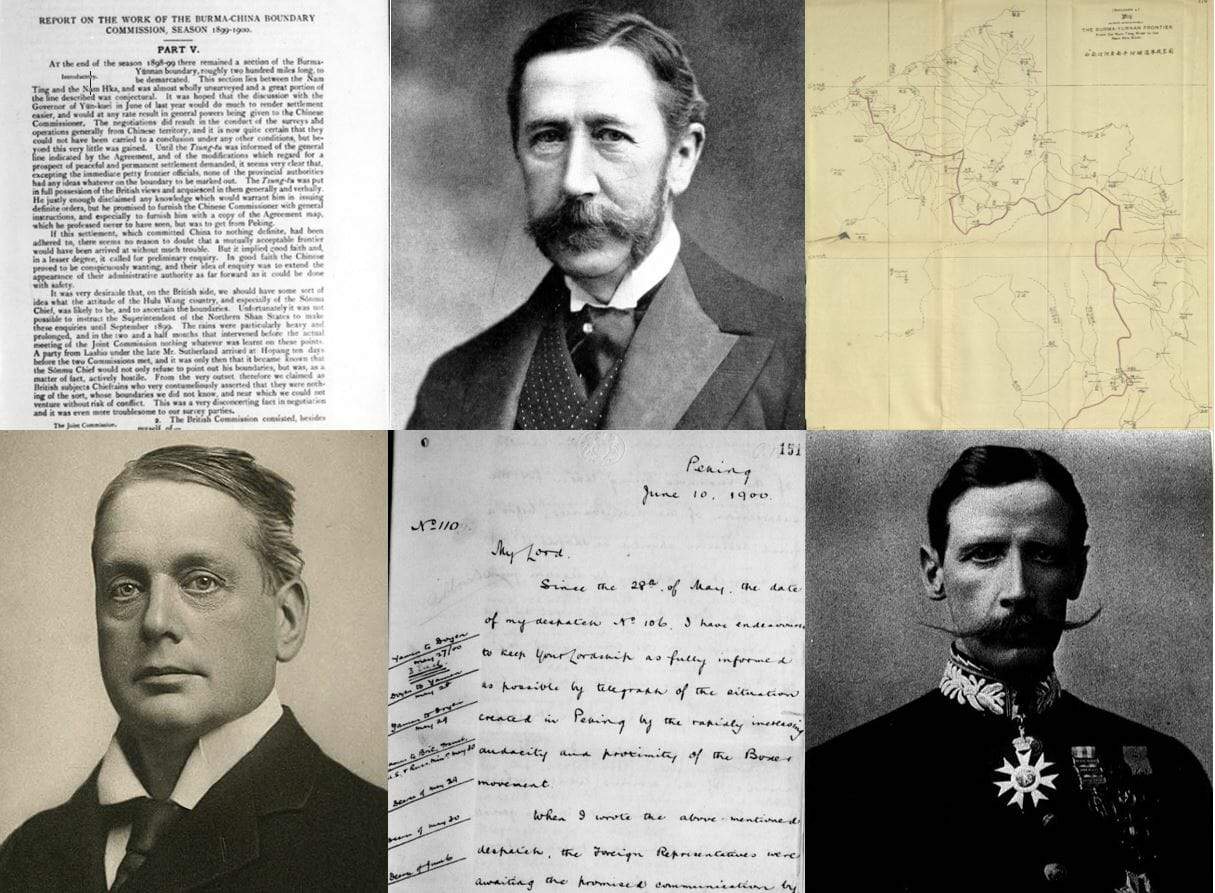

Negotiating the boundary between Burma and China

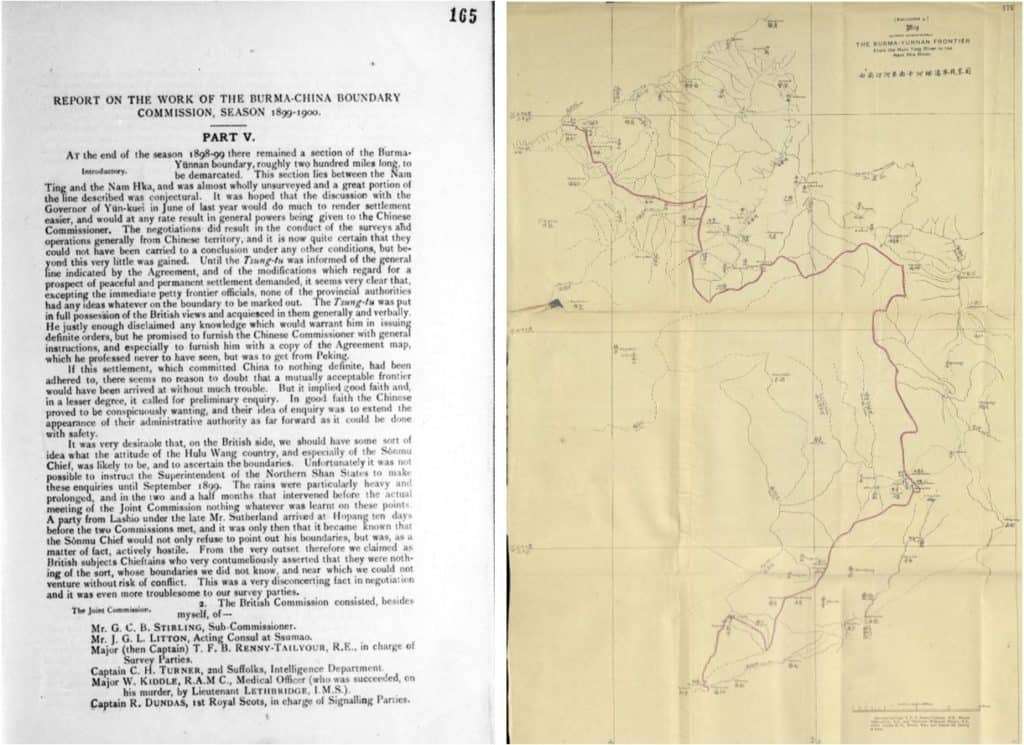

Following the British conquest of the whole territory of Burma and its incorporation into British India as a province in 1886, defining the boundary with China became an important subject in their bilateral relations. The two sides established a Burma-China Boundary Commission to investigate and negotiate their boundary. Below is a page from the commission’s report for its work during 1899–1900 and an enclosed map indicating the frontier between Burma and China’s Yunnan Province with English and Chinese captions.

Left: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IEPBAL641146192/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=f4866821&pg=204,

Right: https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IEPBAL641146192/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=f4866821&pg=216

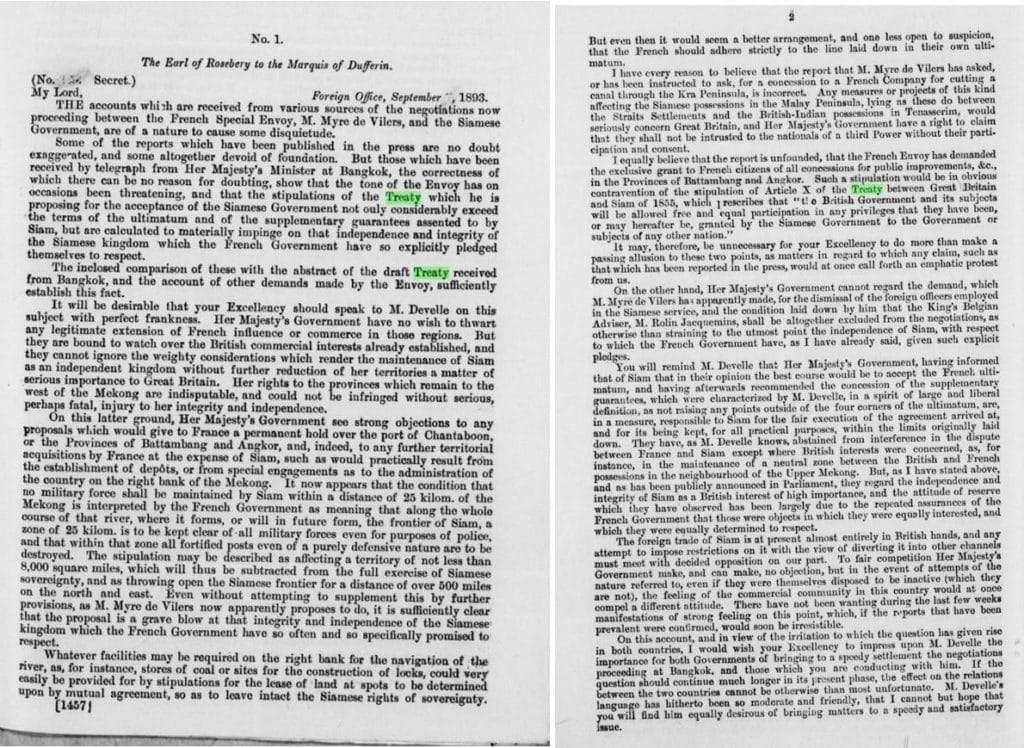

Competition for control of Siam

Thailand or Siam was sandwiched between French Indochina to the east and British Burma and Malaya to the West. Both Britain and France wanted to bring Siam under their own control, leading to a rivalry between the two European powers. The following despatch from the British Foreign Secretary, the Earl of Rosebery, to the British Ambassador to France, the Marquis of Dufferin, describes British reactions to – and worries about – the French ultimatum given to the Siamese government, requesting the latter to withdraw their troops from Laos, and the terms of a treaty France proposed for signing with Siam. The British did not want to see their rights in Thailand infringed on and would have “strong objections to any proposals which would give to France a permanent hold over” ports and provinces of Thailand.

Railway Development

Railway building was one of the concessions Western powers had secured from the Qing Dynasty through various treaties and conventions from the 1890s onward. The benefits of promoting trade and commerce aside, railway construction itself was a very lucrative venture as it would require huge investments in the form of bank loans. Therefore, it was no surprise that from the 1890s to 1905, nearly all railways in China were planned, financed, built, and operated by foreign powers including Britain, France, Russia, Japan, and Germany.

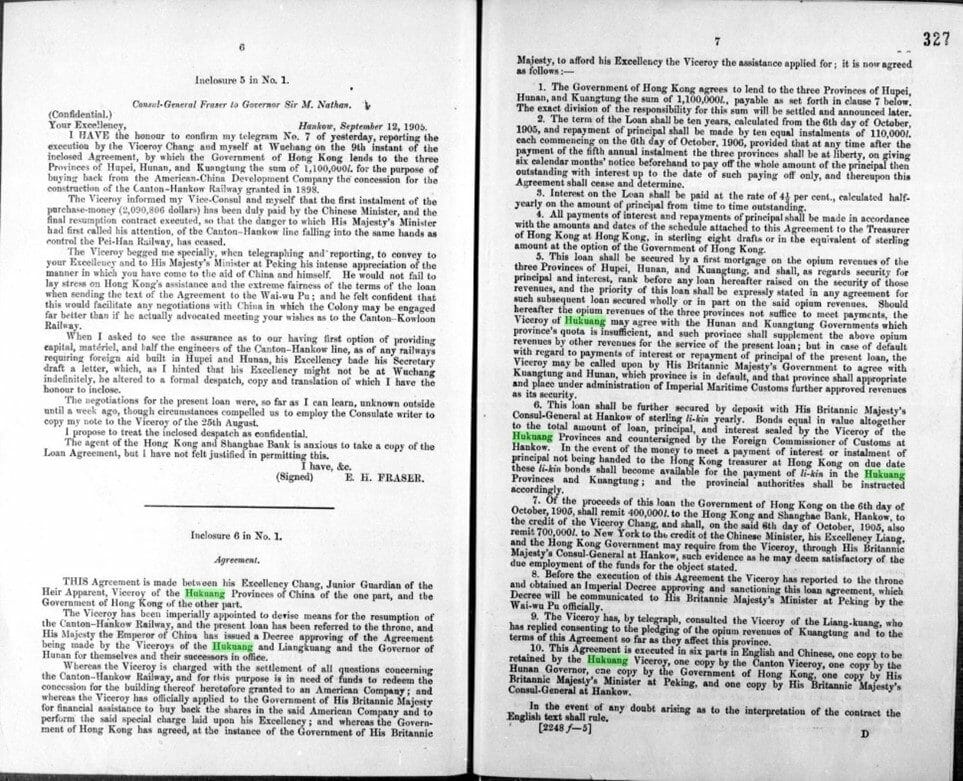

The rights to build railways were sometimes very contentious as both Chinese and foreign companies wanted to have a stake. The concession for building the Canton-Hankow Railway was first granted to the United States but was recovered in 1904 due to a diplomatic crisis involving Belgium and the heavy pressure from Chinese merchants in the provinces of Hubei, Hunan, and Guangdong. To redeem the concession, the Chinese government needed foreign loans. After rounds of negotiations, China and Britain reached an agreement for the British Hong Kong government to lend £1.1 million to the three provinces through the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank. Below are two pages of the loan agreement signed by the Viceroy of Hukuang Chang Chi-tung (張之洞) and the British consul-general at Hankow E. H. Frazer on September 5, 1905.

The Chinese campaigns to recover the railway building rights started in Sichuan Province in 1905 and escalated into the Railway Protection Movement in 1911. Triggered by popular discontent with the Qing regime, the movement galvanized anti-Qing groups and contributed to the outbreak of the Xinhai Revolution inspired by Dr Sun Yat-sen. The Revolution overthrew China’s last imperial dynasty and ushered in a new chapter in the history of modern China.

Hear from the experts!

To learn more about the value of Imperial China and the West for research and teaching, you’re welcome to join a Gale webinar taking place at 10am GMT on November 5, 2021. Registrants will also receive a recording of the webinar, should you be interested but unable to attend the session live.

Webinar Agenda

- Introduction and Welcome – Liping Yang, Publishing Manager, Gale

- Research and Teaching on China’s treaty ports with the FO 17 Collection – Dr Isabella Jackson, Trinity College Dublin

- Using FO 17: A Case Study of Hu Xueyan and China’s First Foreign Loans – Zhiqing Hu, PhD candidate, Birkbeck, University of London

Webinar Speakers

If you enjoyed reading about the second module in Gale’s Imperial China and the West archive, you may like to read Liping’s blog post about the first module:

You may also like:

- An American Missionary with Two Motherlands: Joseph Beech and West China Union University

- The George Macartney Mission to China, 1792–1794

- Who is the Founder of Modern Singapore?

To read more about the fascinating material included in this archive, check out these Content Highlights in the Archives Explored hub of the Gale website, which cover:

- Lord Amherst’s Mission and Revisionist Scholarship

- Western Chinese-language experts: Karl Gutzlaff and Thomas Wade as Translators

- The anti-Christian Tientsin Massacre in the Press

- Guo Songtao and Zeng Jize Defending Chinese Interests

- Historical Maps of China

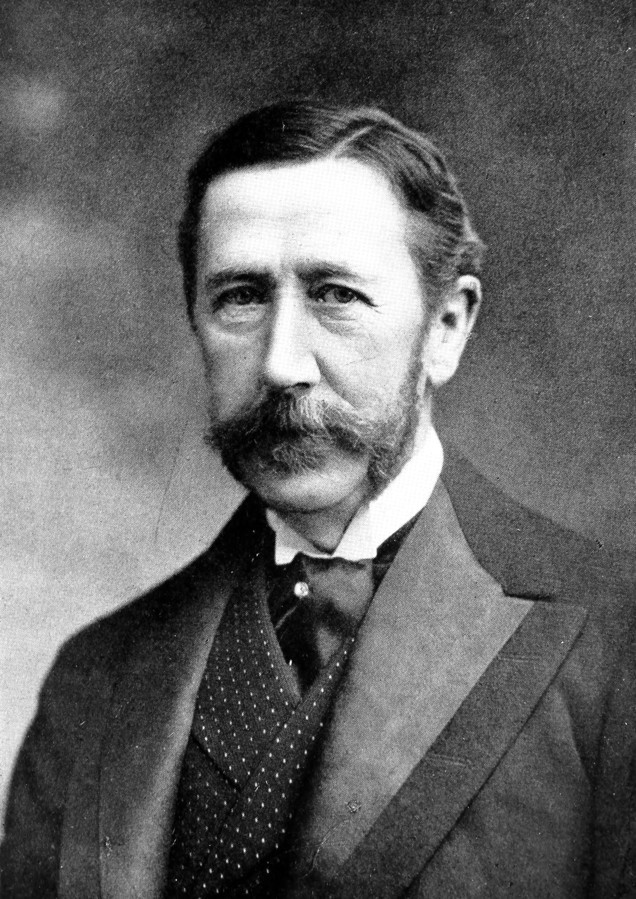

Blog post cover image citation: montage of images from the blog post, combined with photos of individuals featured in this blog post – Sir Nicholas Roderick O’Conor, British Minister to China (available on Wikimedia), Sir Claude MacDonald, British Minister (available on Wikimedia) and Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery – 1890s (available on Wikimedia).