|By Tetsuhiko Mizoguchi, Senior Marketing Executive, Gale Japan|

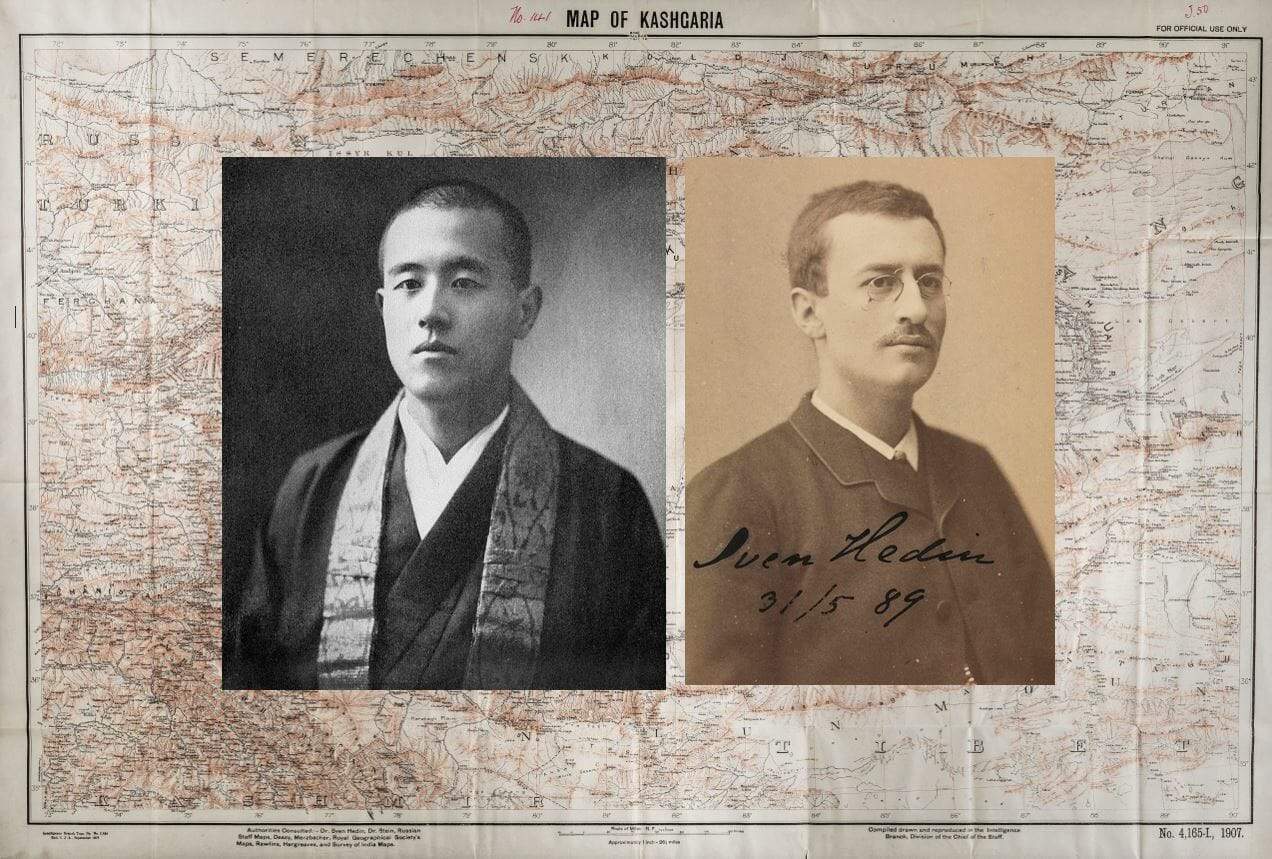

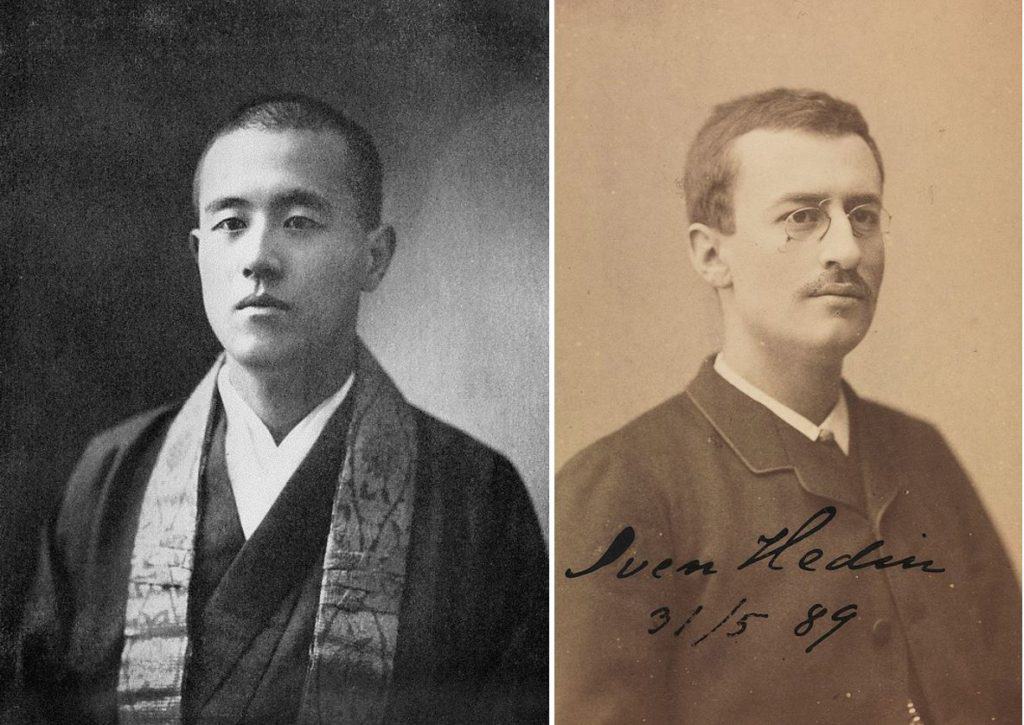

If you have been to Kyoto in Japan, you might have dropped in at the temple of Nishi Honganji. As the head temple of the Jodo Shinshu Buddhist sect, it attracts many tourists and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1994. Even if you stopped by at the temple, however, you might not know that it plays a fascinating part in the history of archaeological expeditions of Central Asia. Kozui Otani was the twenty-second abbot of Nishi Honganji temple. He also led exploratory expeditions, and came to exchange letters with Sven Hedin, a famous Swedish explorer, who even visited the Nishi Honganji temple during his trip to Japan.

Digging through Gale’s digital archive China and the Modern World: Diplomacy and Political Secrets, I found that the India Office Records covered not only diplomats and soldiers, but also explorers like Otani, Hedin and many others. Why? Central Asia, where these explorers were operating, was also the stage on which Western countries played an intelligence war called the “Great Game”. This blog post attempts to shed light on the involvement – or entanglement – of explorers in the Great Game, through the example of Otani and Hedin.

Kozui Otani and the Royal Geographical Society

Kozui Otani was born in 1876 as the eldest son of the twenty-first abbot of Nishi Honganji temple. In 1899 at the age of 22 he left Japan for Britain, wanting to experience a Western country and broaden his knowledge. In London he attended institutions such as the British Library and found himself enthralled by the Royal Geographical Society. The Royal Geographical Society was founded as a learned society in the early nineteenth century, but it was also linked to colonial expansion in Asia and Africa. At the turn of the century, stories of great archaeological discoveries made in Central Asia were reported back to the Society. As a result, Otani, who often attended the Society meetings and had become a regular member, was kept informed of progresses made in Central Asia, and was soon captivated by an ambition to become an explorer himself!

A Letter from Sven Hedin, Legendary Explorer

In 1902, Otani and his fellow explorers left London for Central Asia. But Otani had to quit in the middle of the expedition and return to Japan in 1903 when he received news that his father died. He was planning a second expedition to Central Asia when he received a letter from Sven Hedin, asking Otani for help in his plans to explore Tibet. Hedin was already a legendary explorer having explored the mystery of the wandering lake of Lop Nor and discovered the ruins of the ancient city Loulan. In contrast Otani was still little known as an explorer. So why did Hedin ask Otani for help? To understand, we need to take a look at contemporary international politics around Tibet.

Right: Sven Hedin, 31 May 1889 Available on Wikimedia.

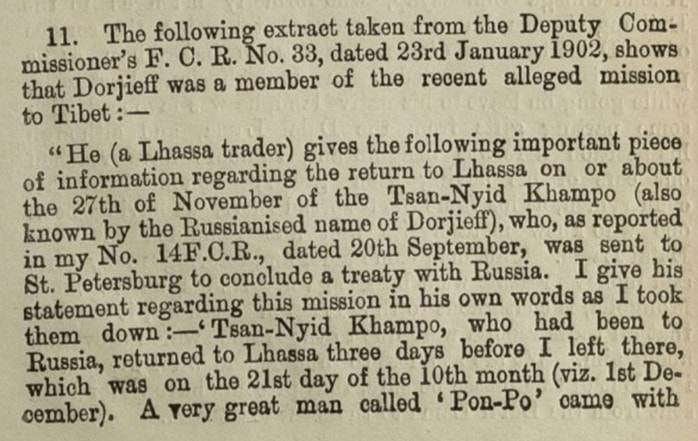

Tibet as a Frontier of Intelligence Wars

Tibet had been a closed country under the suzerainty (partial control) of China. No foreigners were allowed in. Tibet, however, lay in a location of strategic importance for the great powers. Britain sought to defend India, the “crown jewel” of its empire, whereas Russia was expanding its sphere of influence southwards. Britain made several attempts to make Tibet a buffer zone, which you can read about in this blog post about the origins of Sino-Indian border disputes. In the early twentieth century, several sources brought secret information to British India that Tibet was leaning towards Russia. The following file from the India Office Records shows that a Mongolian-Russian named “Dorjieff” was leading missions between Russia and Tibet.

Anxious to exclude Russia’s influence from Tibet, Britain began negotiations with Tibet but soon reached a deadlock. In 1904, British India invaded Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet, and concluded a treaty with Tibet. Tibet was thus about to become an open country when the fall of the Conservative government in Britain in December 1905 caused Lord Curzon, then Viceroy of India, to step down. John Morley, the new Secretary of State for India, brought Tibet back to a closed country again. This decision came as a surprise to many, but Swedish explorer Hedin was particularly upset by the news!

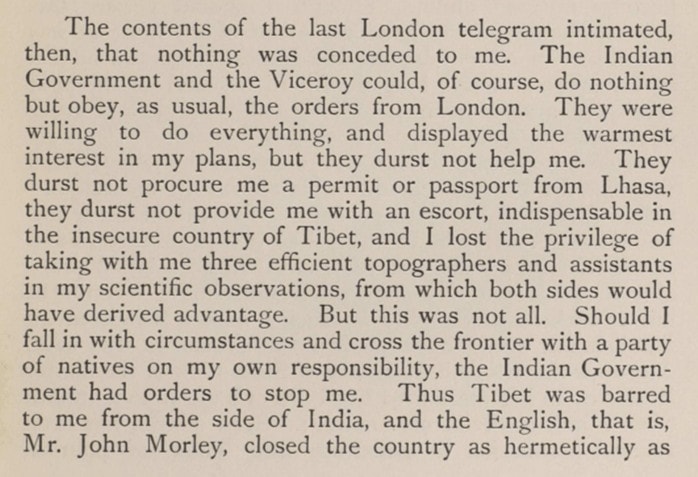

Hedin Attempts to Enter Tibet

Hedin had been planning an expedition to Tibet endorsed by Lord Curzon. Hedin arrived at Simla in India in June 1906, when the British policy towards Tibet was reversed, and was rejected entry by British India. Later he described his frustration in his book as follows:

Thus Tibet was barred to me from the side of India, and the English, that is, Mr. John Morley, closed the country as hermetically as ever the Tibetans had done.

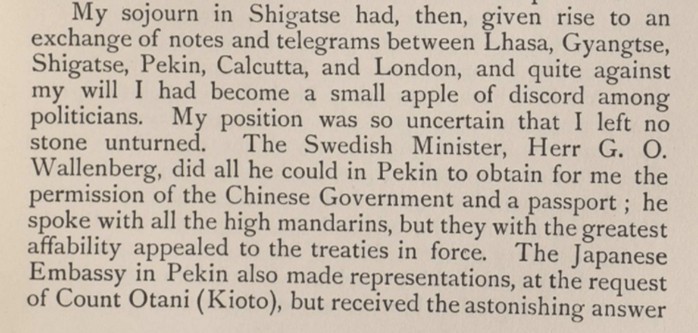

Rejected by British India, Hedin tried to enter Tibet from Xinjiang, China, and asked the Swedish Minister in Peking for help to obtain a passport. It was in this context that he wrote to Otani. When Otani received Hedin’s letter, he was leaving Japan for China to carry out a Buddhist mission. To help Hedin enter Tibet, Otani attempted a negotiation with the Chinese government – but failed. Hedin describes their efforts as follows:

The Swedish Minister, Herr G. O. Wallenberg, did all he could in Pekin to obtain for me the permission of Chinese Government and a passport; he spoke with all the high mandarins, but they with the greatest affability appealed to the treaties in force. The Japanese Embassy in Pekin also made representations, at the request of Count Otani (Kioto), but received the astonishing answer that, if I were Tibet at all, which was very doubtful, I must be at once expelled from the country. So I met with refusals on all sides.

Hedin Spends Two Years in Tibet (1906-1908)

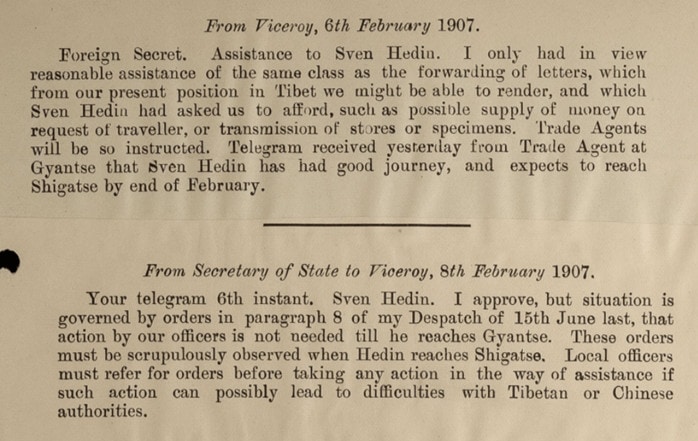

However, even in the face of refusals from all sides, Hedin did not abandon his plan. He boldly forced himself into Tibet and stayed there for two years. A 108-page file from the India Office Records titled “Part 3 Tibet: Travellers; Dr Sven Hedin (1906-1908)” is dedicated to Hedin’s Tibet visit.

Hedin’s Visit to Japan

When Hedin was in Simla, returning from Tibet, he received a letter from Otani inviting him to Japan. Hedin accepted, and arrived in Japan in November 1908. During the stay, he attended many receptions and banquets hosted by politicians and the academic community. As a matter of course, he visited Nishi Honganji temple and met Otani in person for the first time. It was a golden opportunity for Otani.

The Great Discovery of the Otani Expedition

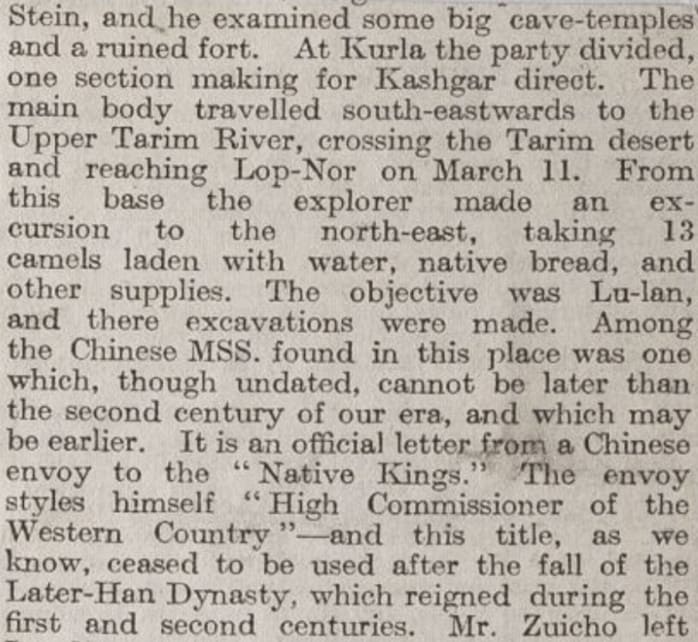

About six months earlier, Otani had been remotely involved in an expedition, led by Zuicho Tachibana and Eizaburo Nomura, to excavate the ruins of Loulan (the ancient city first discovered by Hedin). But Loulan was very difficult to locate. When Otani met Hedin, perhaps Otani lamented this difficulty, hoping Hedin would provide the location. It seems Hedin obliged! He provided the exact location of Loulan. This information was sent to Tachibana in an encrypted telegram, and led Tachibana to Loulan and thus to a great discovery: Li-bai-wen-shu (李柏文書), an ancient Chinese manuscript which dates back to the fourth century. One file from the India Office Records contains a clipping from the Times of London. The article titled “Exploration in Chinese Turkestan” describes Tachibana’s discovery at Lulan (Loulan).

Perceived Within the Context of the “Great Game”

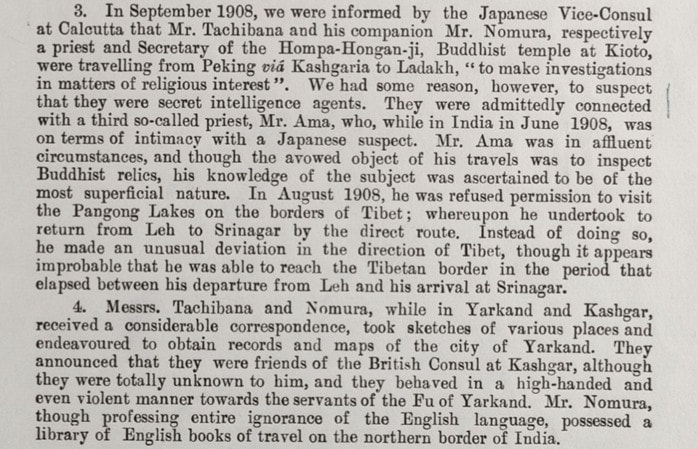

Before Tachibana made his discoveries at Loulan, however, British civil officers had sent a secret report on the Japanese explorers to the Secretary of State for India.

In September 1908, we were informed by the Japanese Vice-Consul at Calcutta that Mr. Tachibana and his companion Mr. Nomura, respectively a priest and Secretary of the Hompa-Hongan-Ji, Buddhist temple at Kioto, were travelling from Peking viá Kashgaria to Ladakh, “to make investigations in matters of religious interest”. We had some reason, however, to suspect that they were secret intelligence agents.

As this report shows, Tachibana and Nomura were suspected to be Japanese secret intelligent agents! This is not surprising as, whilst they were explorers, in the “Great Game of Central Asia” it was not only diplomats and soldiers that acted politically – explorers often acted as spies under cover of archaeological expeditions. As a result, anyone who moved around the region was treated with suspicion; no one knew who was a secret agent and who was not, which is why the British India Office kept a close watch on their activities. China and the Modern World: Diplomacy and Political Secrets illuminates the fascinating stories of those involved – or entangled within – the “Great Game”.

If you enjoyed reading about the expeditions of explorers Otani, Hedin and how they fitted within the “Great Game” you may enjoy:

- George Macartney, Kashgar and the Great Game

- Simla, McMahon, and the Origins of Sino-Indian Border Disputes

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- Indentured Indian Workers and Anti-Colonial Resistance in the British Empire

- Sun Yat-sen and the Kwangtung–Kwangsi Conflicts in the 1920s

- Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the man who led China from Empire to Republic

- Researching Infectious Diseases in Colonial India

Bibliography

Hopkirk, Peter, Trespassers on the Roof of the World. London: John Murray. 1982

Kaneko, Tamio, Seiiki Tanken no Seiki. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten. 2002.

Shirasu, Joshin (ed.), Otani Kozui to Sven Hedin. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan, 2014.

Blog post cover image citation: Military Report on Kashgaria Simla: Intelligence Branch, Division of Chief of Staff, 1907. 1907. TS Political and Secret Department Records: Series 20: Political and Secret Department Library (1757-1952): ‘A’ Books (1834-1929) IOR/L/PS/20/A108. British Library. China and the Modern World. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AYGNIV229304038/CFER?u=asiademo&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=22ff85bb&pg=4, combined with photos of the explorers featured in this blog post.