|By Winnie Fok, Assistant Editor, Gale Asia|

In February 2019, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government proposed a bill regarding extradition, to establish a mechanism for the transfer of fugitives to Mainland China, Taiwan, and Macau, which are currently excluded in the existing laws. The bill sparked fears over a potential loss of freedom and deterioration of the business climate in Hong Kong. As a result, protests erupted over the next few months, and lasted till early 2020. Extradition has a long and complex history in Hong Kong, owing in no small part to its colonial background. China and the Modern World: Hong Kong, Britain and China 1841–1951, a collection of rare historical materials from the British Colonial Office records, sheds light on this fascinating subject.

The Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1889

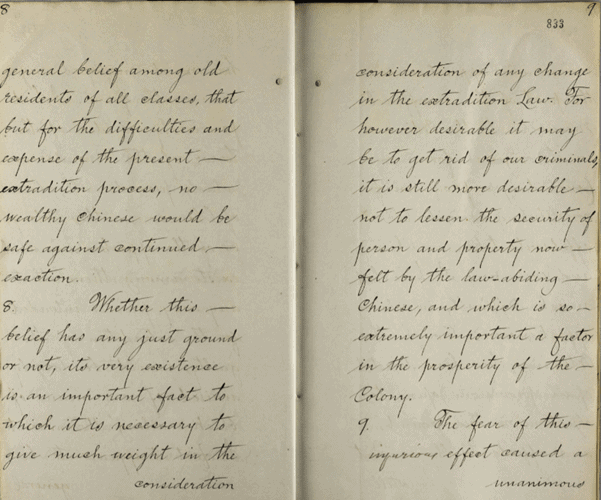

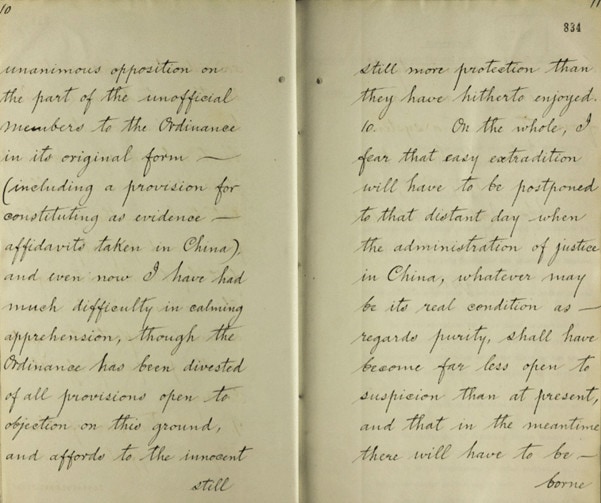

The concerns expressed today are not new—in fact, they were factored into the early formulation of Hong Kong’s extradition arrangements leading up to the Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1889. The matter provoked widespread apprehension among the Chinese in Hong Kong, who believed that “any easy process intended for the extradition of the guilty, would be largely availed of as a means of ‘blackmailing’ the innocent.” British correspondences at that time reflect the colonial government’s struggle to soothe the general insecurity of the residents.

The colonial government’s primary concern was to safeguard the perceived security of those in the colony, an aspect deemed essential to the continued prosperity of the colony. Hence, with regard to such strong sentiments of anxiety, the British did not intend for maximum ease of extradition in their design of the Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1889.

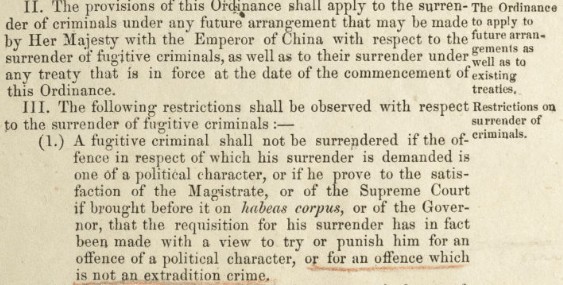

Restrictions within the Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1889

A key aspect of the ordinance was the restrictions it applied to the type of criminals that could be extradited to China. In alignment with British principles, the ordinance did not permit the extradition of individuals accused of criminality of a political nature. This restriction protected Chinese radicals such as Kang Youwei and Dr. Sun Yat-sen who fled to the colony after the abortion of the short-lived constitutional reform of 1898 and revolutionary uprisings. However, this would prove to be a sticking point decades later.

The Flaws of the Extradition Law, Exposed by China’s Changing Political Landscape

China’s political landscape experienced tremendous earthquakes in the decades following the passing of the Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1889. Through the Revolution of 1911, the Qing Dynasty gave way to the Republic of China. The country was ruled by the Beiyang Government based in Peking, which was challenged in 1917 and later overthrown between 1926 and 1928 by the National Government based in Kwong Tung (often spelt as “Canton” and now “Guangdong”).

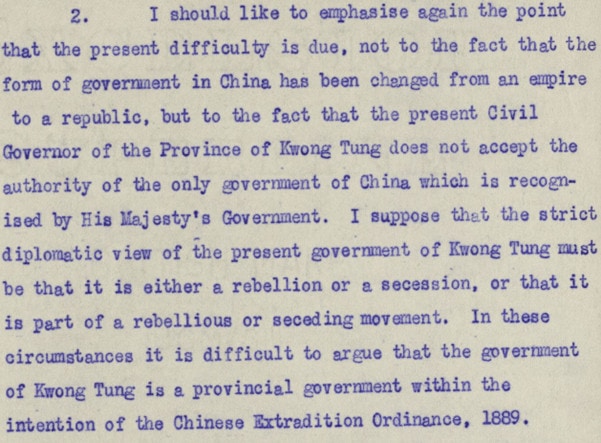

For a considerable period of time the British maintained ambivalence in its official view of this new, separate government in Canton, refraining from expressing any definitive recognition of it amidst a still uncertain political climate in China. This ambivalence hindered its official dealings with the Chinese authorities, particularly in relation to the neighbouring Canton Government, which did not fit the definition of “a provincial government within the intention of the Chinese Extradition Ordinance,” as its Civil Governor did not “accept the authority of the only government of China which [was] recognised by His Majesty’s Government” (that is, the Beiyang Government).

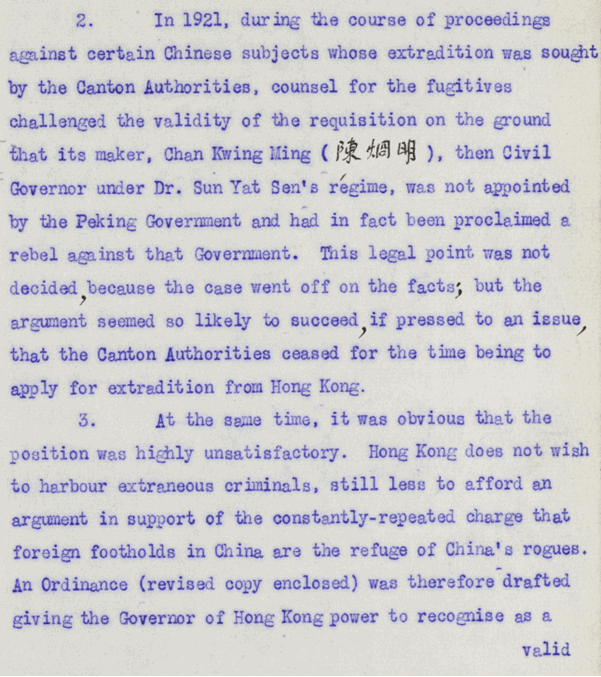

As a result, the arrest and extradition of Chinese criminals who escaped to Hong Kong after committing crimes in China was impeded, gradually unearthing the shortcomings of the Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1889. The British colonial government hence found itself at an impasse, caught between seeking to “satisfy the Ordinance while avoiding any undesirable recognition of the Kwong Tung Government.” This significant conundrum led to the indefinite suspension of extradition between the two governments.

The Case of Lau Lun

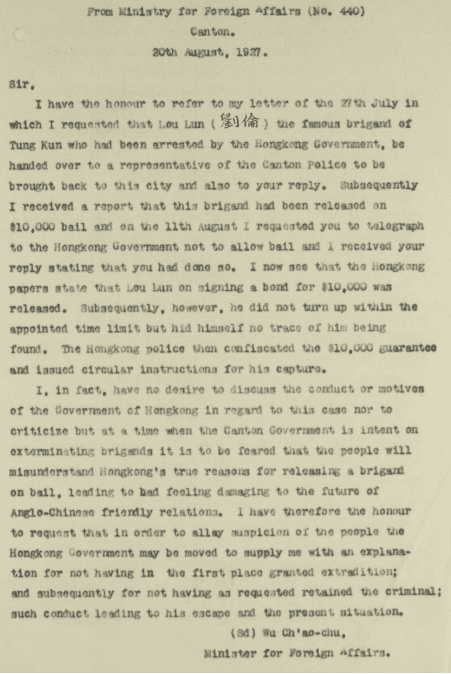

The matter came to a climax in the 1927 case of Lau Lun (劉倫), a notorious robber chief whom the Canton Government had requested be extradited to them. With the extradition proceedings unable to circumvent this legal loophole, the British colonial government instead released Lau Lun on bail, on the bewilderingly naïve condition that he obediently report to the Police Headquarters every other day pending his trial and execution. The result was that Lau Lun, unsurprisingly, vanished, and the British colonial government found itself having to sheepishly inform the Canton Government that their wanted criminal had “in all probability left the Colony.”

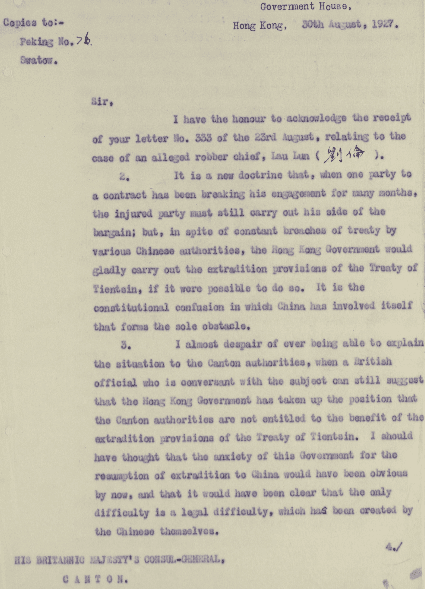

As one might expect, Canton came back with a withering response, dripping with disdain at how the colony had somehow opened the door wide for the fugitive to leave. What followed was a string of correspondences between the two governments, laced with bickering, finger-pointing, and veiled jabs. The remarkably sarcastic and frankly entertaining letters expose the strained relations between them, owing to reasons beyond the isolated case of Lau Lun. Each found the other remiss in upholding the terms of the treaty between them. One particular sore spot was the larger issue of piracy, of which Lau Lun was one example—the British colonial government blamed the Canton Government for its paltry handling of piracy, whilst the latter blamed the former for making Hong Kong such good refuge for rogues.

Diplomatic and Reputational Risks Create Pressure to Amend Extradition Law

The situation presented several predicaments to the British colonial government. The first concerned the health of its relations with the Canton Government, which it had otherwise construed to be friendly. This matter however endangered not only the air of friendliness between them but also the strength with which the colonial government could demand treaty observance from the Canton Government, given its own inability to deliver on its own obligations.

The second was the threatened reputation of Hong Kong (which was already often regarded as a hideout for rogues), and of the British colonial government, (which was at risk of being perceived and condemned as obstructing the course of justice).

The Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1927

The fallout of the Lau Lun saga ramped up pressure on the British colonial government to amend the extradition laws. Hence they undertook to formulate amendments. A significant difficulty in the process was the colonial government’s continued tiptoeing around the degree and definitiveness of recognition they would afford to the Chinese authorities.

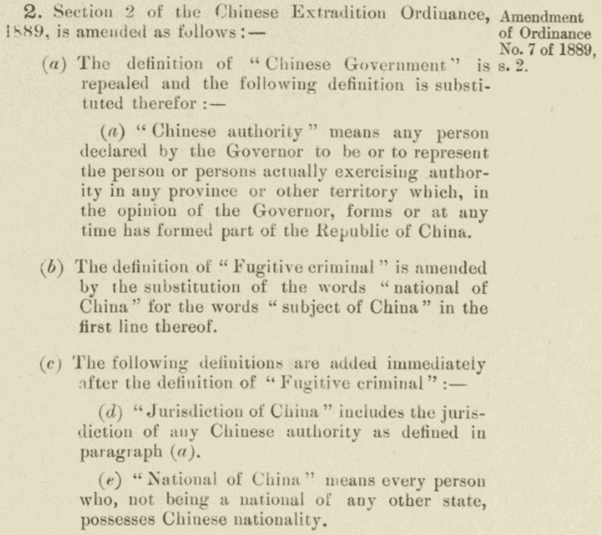

The suggestion was made several times to limit the recognition of the Canton Government to the purposes of extradition, or even to a singular ‘test case’ of extradition. Ultimately, however, this was deemed unfeasible, and the final Chinese Extradition Ordinance of 1927 reprised the original term “Chinese Government” to the broader term “Chinese authority,” which would suffice to permit dealings with China’s then still fluid governing bodies.

Extradition resumes

Quickly following its amendment, the new ordinance saw immediate use. Extradition proceedings resumed in multiple cases thereafter, but the still-remaining restriction against extraditing those accused of crimes of a political nature continued to be a thorn in Canton’s side and in its relations with the British colonial government.

One of the first instances of this occurred barely two months later, following the outbreak of the Canton Uprising in December 1927. The incident saw an exodus of political refugees from Canton, wherein 246 Chinese nationals entered and were detained in Hong Kong. Owing to the fact that the ordinance did not allow Canton’s demand for their extradition, they were instead deported from the colony.

This is undoubtedly a fascinating period of history, with significant and long-term impacts. A great deal of historical background and context can be found, and analysis undertaken, within the rich research resource of the British Colonial Office Files from the UK National Archives, now included in Gale’s China and the Modern World: Hong Kong, Britain and China 1841–1951.

If you enjoyed reading about the history of extradition in Hong Kong, you may enjoy:

- Discover the History of British Hong Kong Through Handwritten Documents – Now Available in “Easy Mode”!

- Tears, Cheers, The Archers, and Soy Sauce: The Hong Kong Handover of 1997

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- George Macartney, Kashgar and the Great Game

- One Treaty, a Diplomat, and Three Countries

Blog post cover image citation: Victoria City, Hong Kong, circa 1920. Available on Wikimedia.