│By Clem Delany, Associate Acquisitions Editor, Gale Primary Sources│

The twentieth century was an era of global conflict and careful diplomacy, of the rise and fall of political extremes, of great strides in technology and vast change in the everyday lives of people around the world. Britain began the century with an empire that straddled the globe, and ended it with just a handful of small overseas territories. Warfare moved from trenches and bayonets, to weapons of mass destruction and long-distance drones. The global population skyrocketed. The internet came to be.

The scope and geographical spread of the interests of the British government over this century was vast. It reached beyond the UK and the mandates, protectorates and colonies of the British Empire, to the affairs of the self-governing Dominions and the later Commonwealth, as well as those of allies and enemies. British interests and British intelligence reached every corner of the globe from Aden to Zanzibar.

Declassified Documents Online: Twentieth-Century British Intelligence, An Intelligence Empire makes available online over half a million pages of British government papers relating to security and intelligence work in the twentieth century. It brings together files from the Security Service (MI5), the wartime Special Operations Executive (SOE) and Ministry of Economic Warfare, the Intelligence and Security Departments of the Colonial Office in the twilight of Empire, communications and intelligence records of the Ministry of Defence, and material from the Cabinet Office, including Joint Intelligence Committee reports, documents from the Special Secret Information Centre of WWII, and papers of the Cabinet Secretary relating to intelligence and espionage matters.

A Sprawling Network of Intelligence

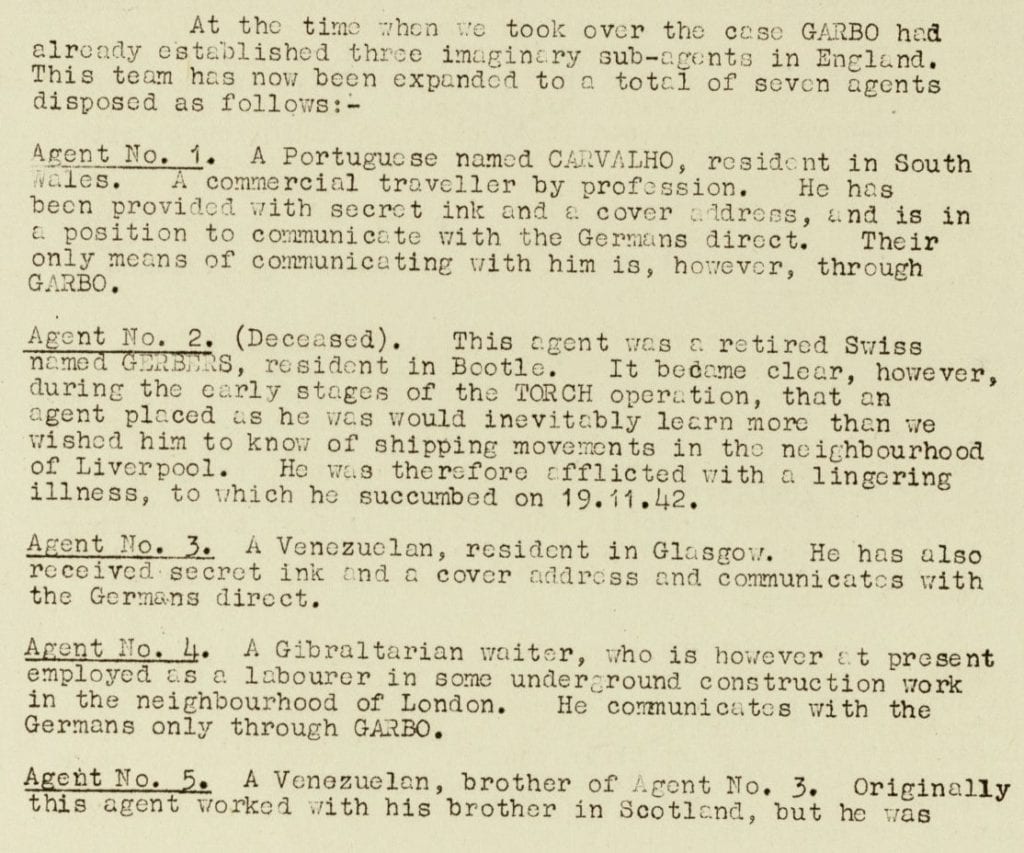

British Intelligence in the twentieth century was a sprawling network of HUMINT, SIGINT, COMINT, ELINT, TECHINT and more – a sea of acronyms pouring out of discrete offices in London and flooding across the world. Much has been written of the work of such agents as Zigzag and Garbo, of Operations like Mincemeat and Overlord, of the breaking of Enigma in a hut in Buckinghamshire, of the Cambridge Five and of men disappearing behind the Iron Curtain. But behind these headliner stories lay hundreds of people gathering, interpreting, decrypting, translating, analysing, transmitting and processing information over every facet of policy, strategy and diplomacy in Britain and the British Empire.

B1A case summaries prepared for the Twenty (XX) Committee (1941). (30 October 1941). KV 4/92. The National Archives (Kew). http://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BETEZN691905030/TCBI?u=omni&sid=TCBI&xid=f3becc7d&pg=31

War and “Peace”

British intelligence grew into the behemoth it became in part because of the two world wars, the practical need for secrecy and subterfuge in warfare, and the need to monitor events across the large territory of the British Empire. The Second World War in particular is well represented in these papers, as the historical significance of the material was recognised early on, and efforts were made to archive and preserve. The huge amounts of documents generated between 1939 and 1945 also illustrate the hunger for information at all levels; Winston Churchill was a passionate supporter of intelligence work and played a key role in its expansion under his ministry, in particular in the formation of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), to whom he gave the memorable order to “set Europe ablaze!”

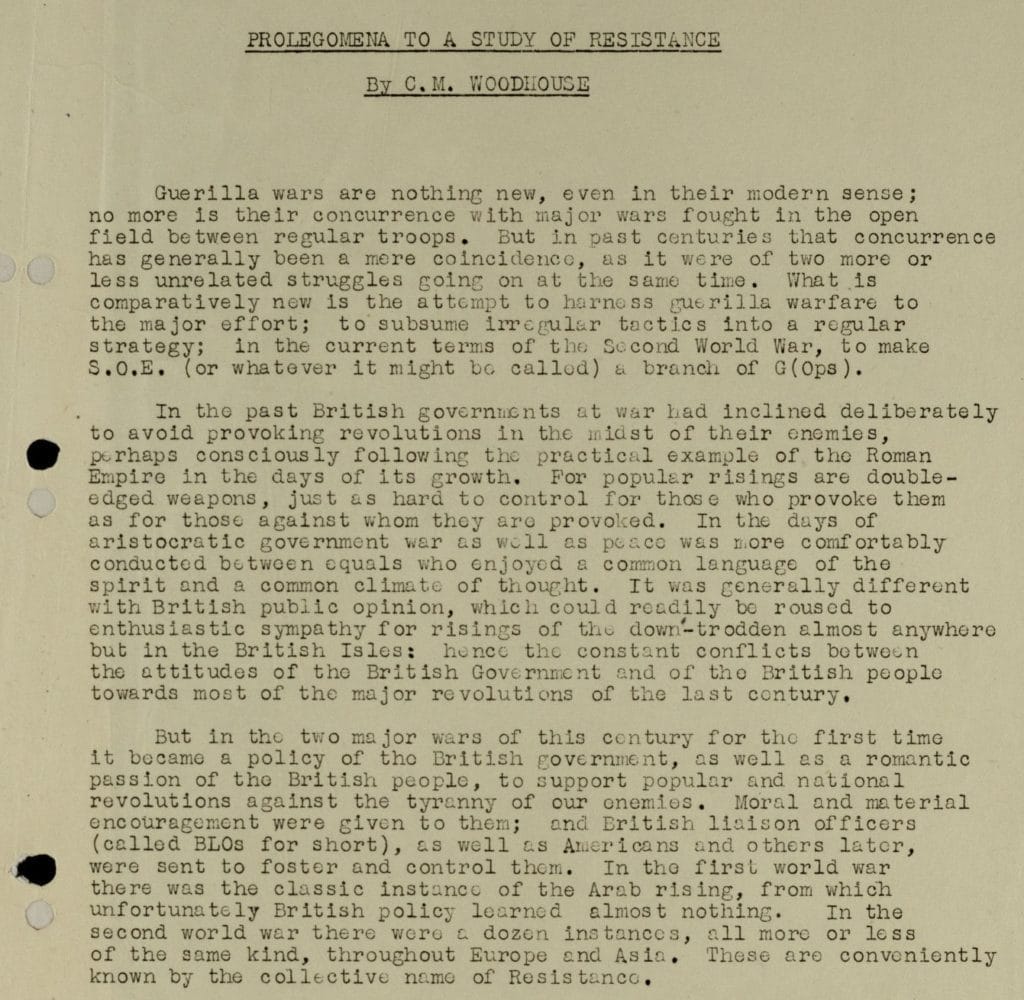

The extent to which the SOE achieved this can be judged in files from the HS 7 and HS 8 series at the UK National Archives, which cover: the work of Operation Jedburgh parachute teams, SOE training in the UK, working with “Chetniks” in what was then Yugoslavia, and the work of Force 136 in the Far East against Japanese occupation. The nature of the work of these SOE units meant they collaborated with local resistance and guerrilla groups, and closely monitored the local and national political situation in the territories where they were active.

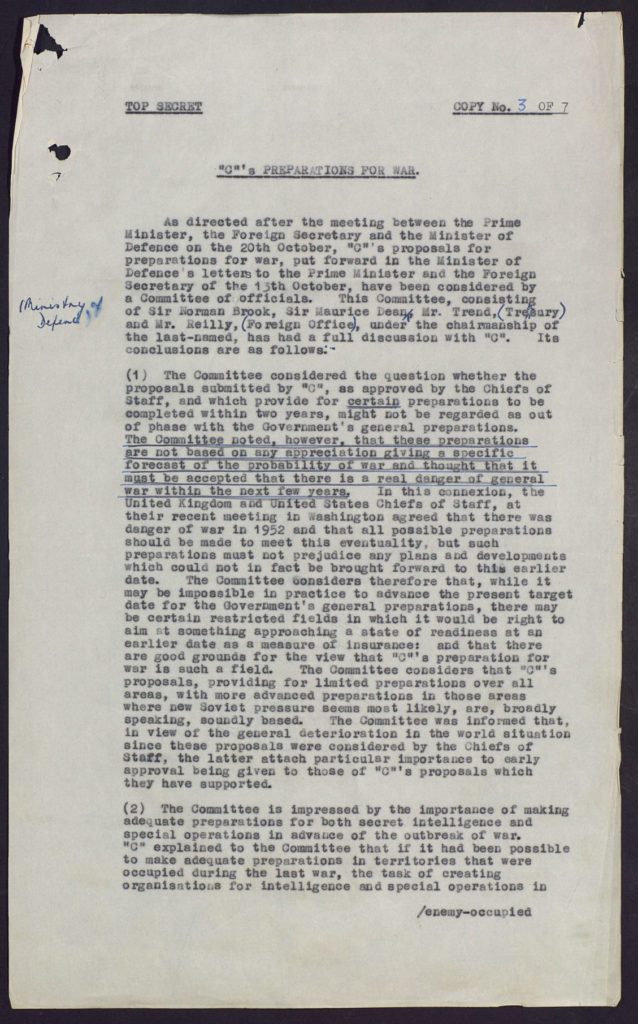

While the SOE did not survive long after the end of WWII (it was dissolved in January 1946), the end of direct conflict did not mean the end of espionage work. British fears of the rise of Communism predated the war against a Fascist regime, and the cautious alliance between Russia and the UK and US during WWII was an uneasy one. The Cold War leant heavily on intelligence work, and documents such as the one below, from the Cabinet Secretary’s Miscellaneous Papers, illustrate how seriously the threat of the Cold War turning hot was taken, and the role intelligence was expected to play in any such event:

Resistance and Independence

From the resistance work against German Occupation during the Second World War, to independence movements in British colonies later in the century, many opposition groups and organisations were closely watched by the British government. Files relating to the Free French, the German Rote Kapelle (Red Orchestra), and other national resistance groups across Europe, show the activities of these organisations, the support given them by the British government and the SOE, the nature of their work, their successes and failures, and the larger strategies into which these resistance movements played.

In the post-war period, independence movements pushing for the end of the British Empire were also closely monitored. The processes and conferences surrounding decolonisation can be traced within these files, with MI5 surveillance of such key players as Hastings Banda, Julius Nyerere and Oginga Odinga as well as coverage of conferences and constitutional developments from Singapore to Jamaica.

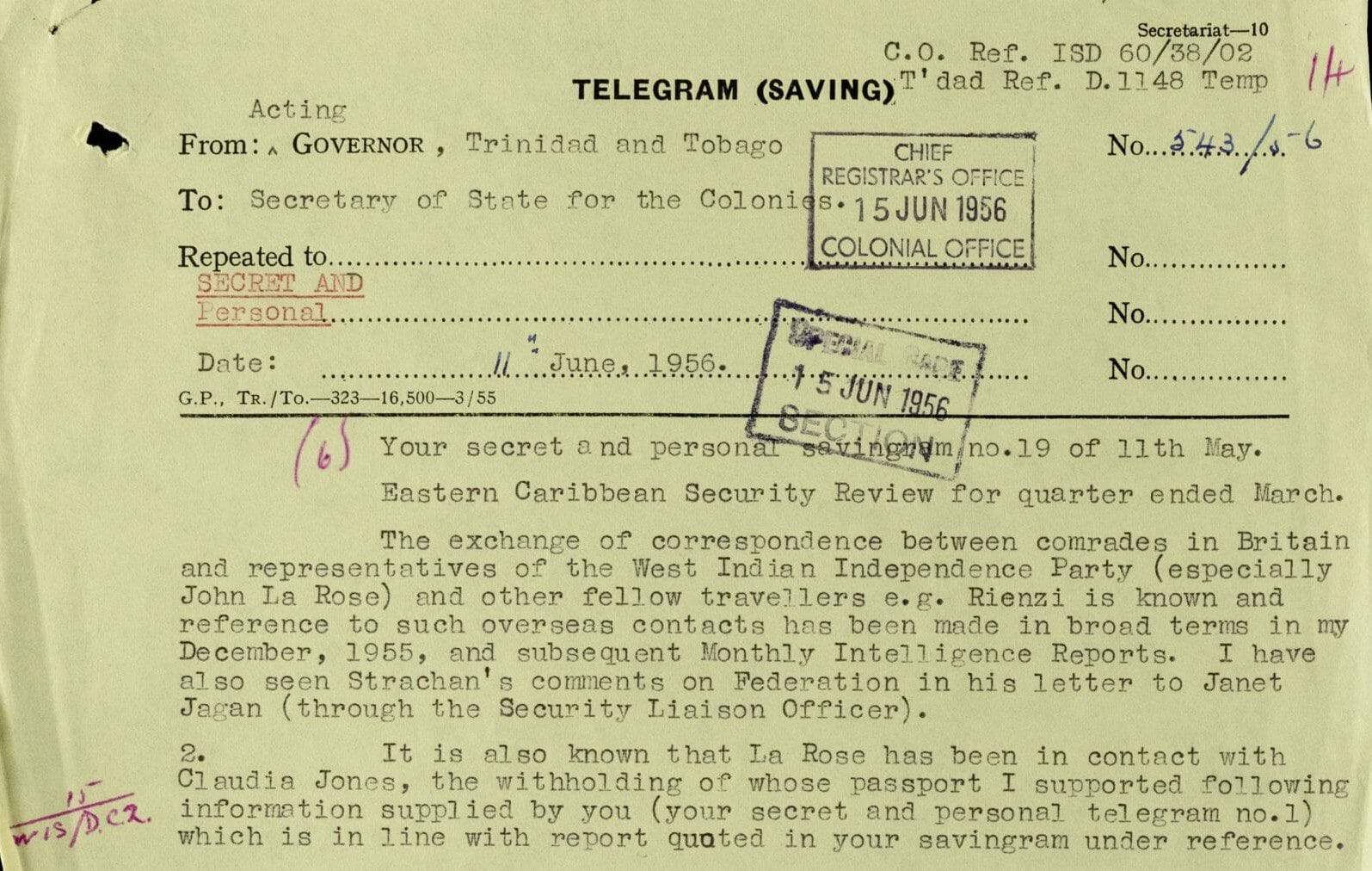

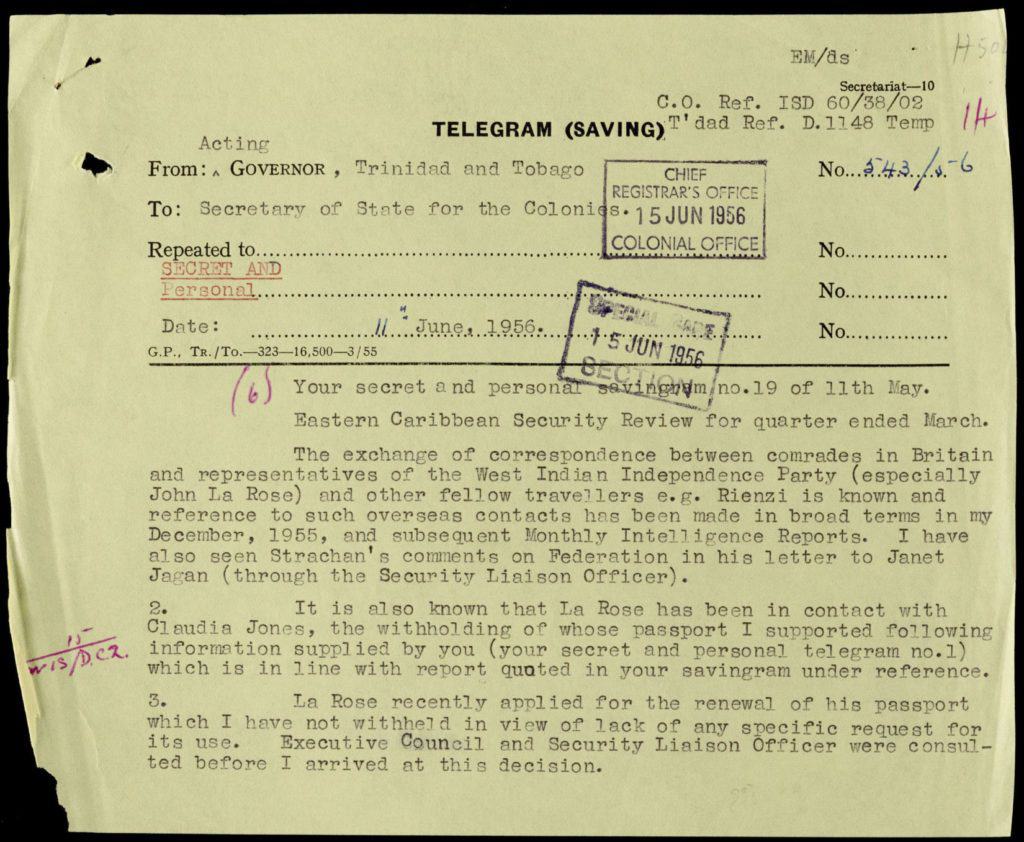

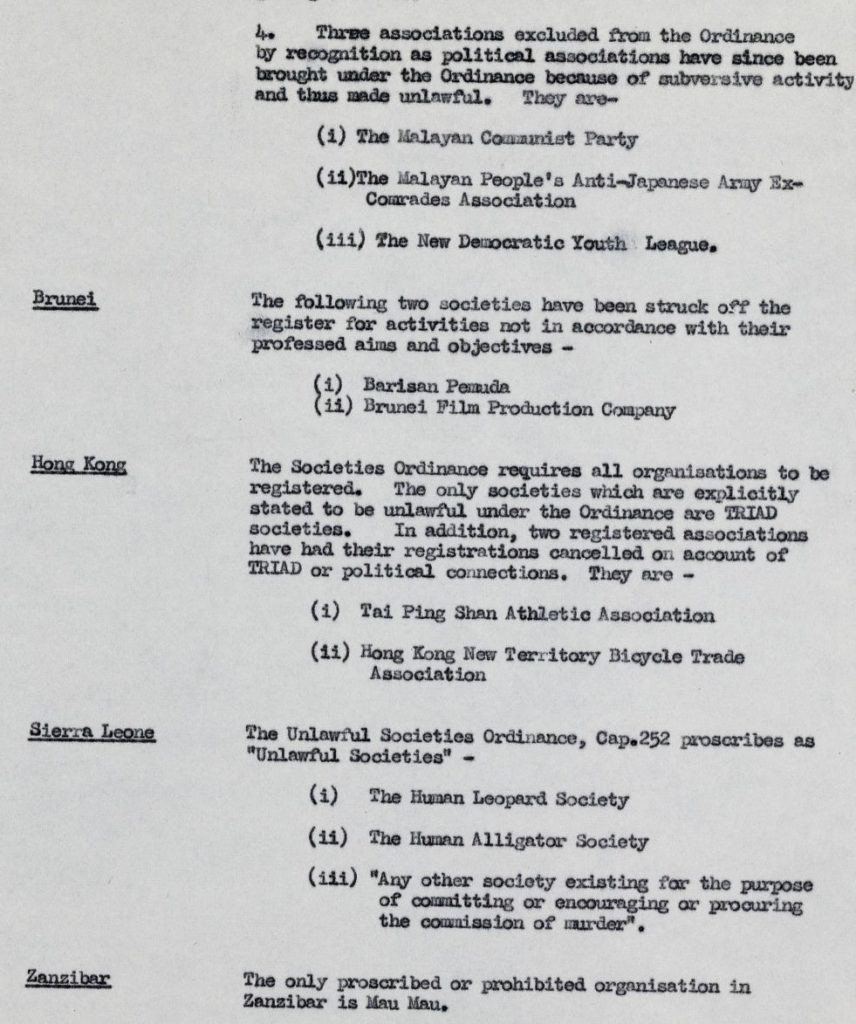

The telegram above from 1956 shows the close watch kept on the activities of West Indian activists, including Claudia Jones, an important figure in the British African-Caribbean community and the founder of what would become the Notting Hill Carnival. Below, a list of proscribed and prohibited organisations in British colonies produced by the Colonial Office illustrates the perception of internal threats to British control, and methods of maintaining this.

Centralised Intelligence

With such wide-ranging interests, bringing together relevant information for analysis and disseminating information to interested parties was its own challenge. In 1936, the Inter-Service Intelligence Committee was established under the Committee of Imperial Defence. This inter-service committee became, later that year, the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee (JIC), composed of the deputy directors of intelligence of the three services and relevant representatives from other departments such as the Foreign Office. While the Committee of Imperial Defence was dissolved in 1939, the JIC continues in this interagency role to this day, bringing together the intelligence gathered by different branches and synthesising it into reports and recommendations for the top levels of government.

The CAB 121 series also exemplifies the need felt by the British government to bring together intelligence material in a useful and usable way. The series consists of files held at the Special Secret Information Centre, which was established in 1941 with the intention of limiting the circulation of secret documents by maintaining a central collection for interested parties in London. Topics covered by these files include post-war plans for Europe and the world, displaced persons, chemical warfare, policy in the Far East and Middle East, and the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel, among much else.

From Invisible Ink to Cellular Telephones

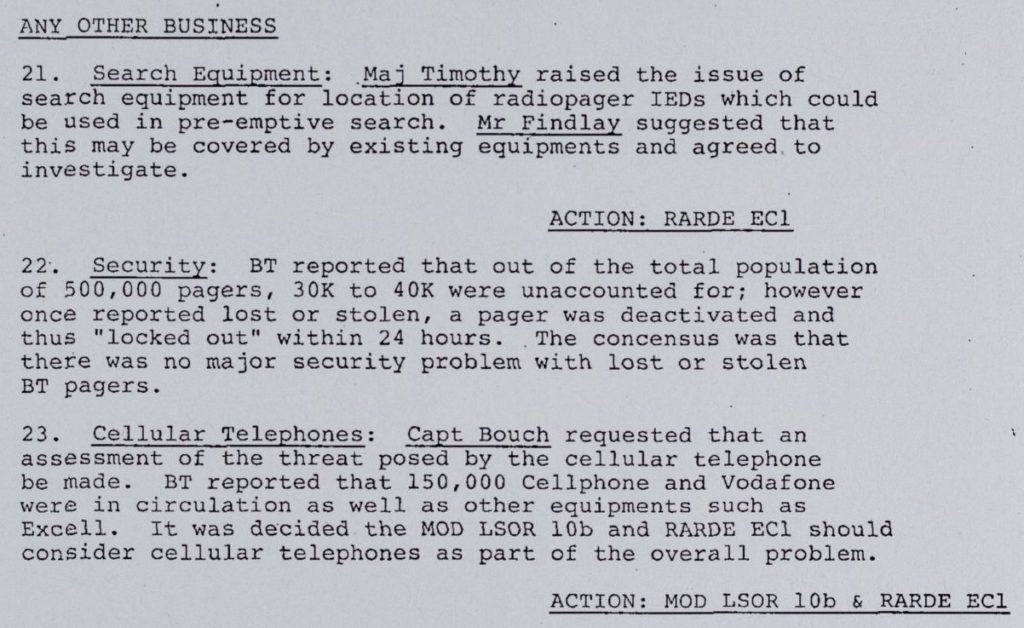

The hardware of spycraft and the technological and scientific interests of the British are also present in this archive, in particular in Ministry of Defence documents from the Directorate of Scientific Intelligence. Concerns over Sino-Soviet technological advances during the Cold War meant a close watch was kept on institutes and academics in Russia, while the assessment of internal threats from new types of technology, including pagers and cellular telephones, also came within the purview of the MoD.

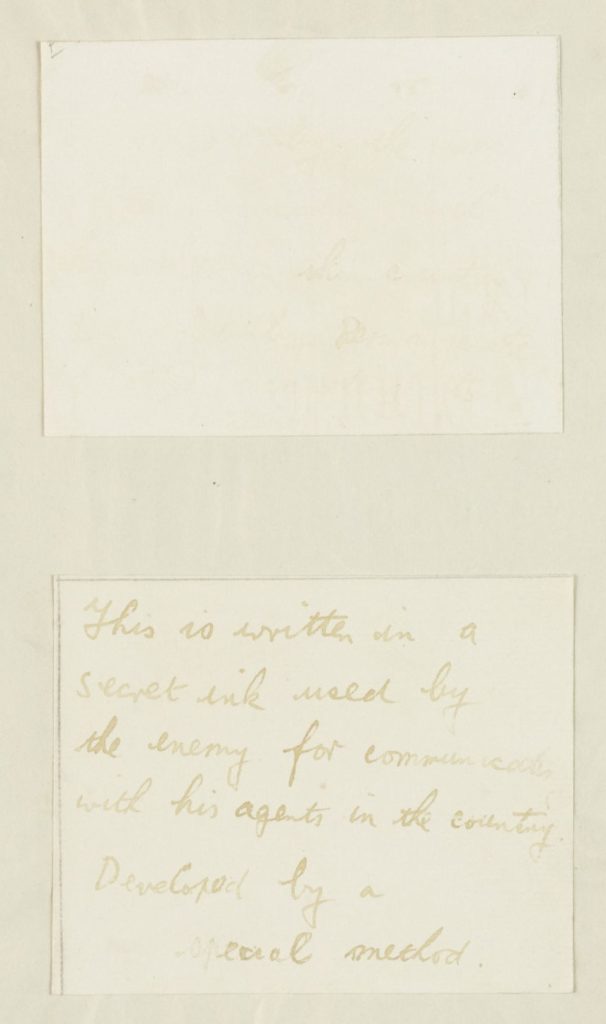

Earlier examples of the tools of espionage include invisible ink, one-man Welman submarines, and micro-photography.

Legacies of the Twentieth Century

Today, an increasingly globalised world confronts threats from extremist terrorism both foreign and domestic, cybersecurity issues and political and social division. Looking back on the twentieth century from an intelligence perspective can help us understand how the geopolitics of the twenty-first century developed, and how the world as we know it came to be. By bringing together material from across security and intelligence branches, Declassified Documents Online: Twentieth-Century British Intelligence, An Intelligence Empire will help scholars and researchers delve into the role of intelligence in theory and in practice, while newly declassified pieces offer possibilities of new research and new readings of historical events from WWI to the Cold War and beyond.

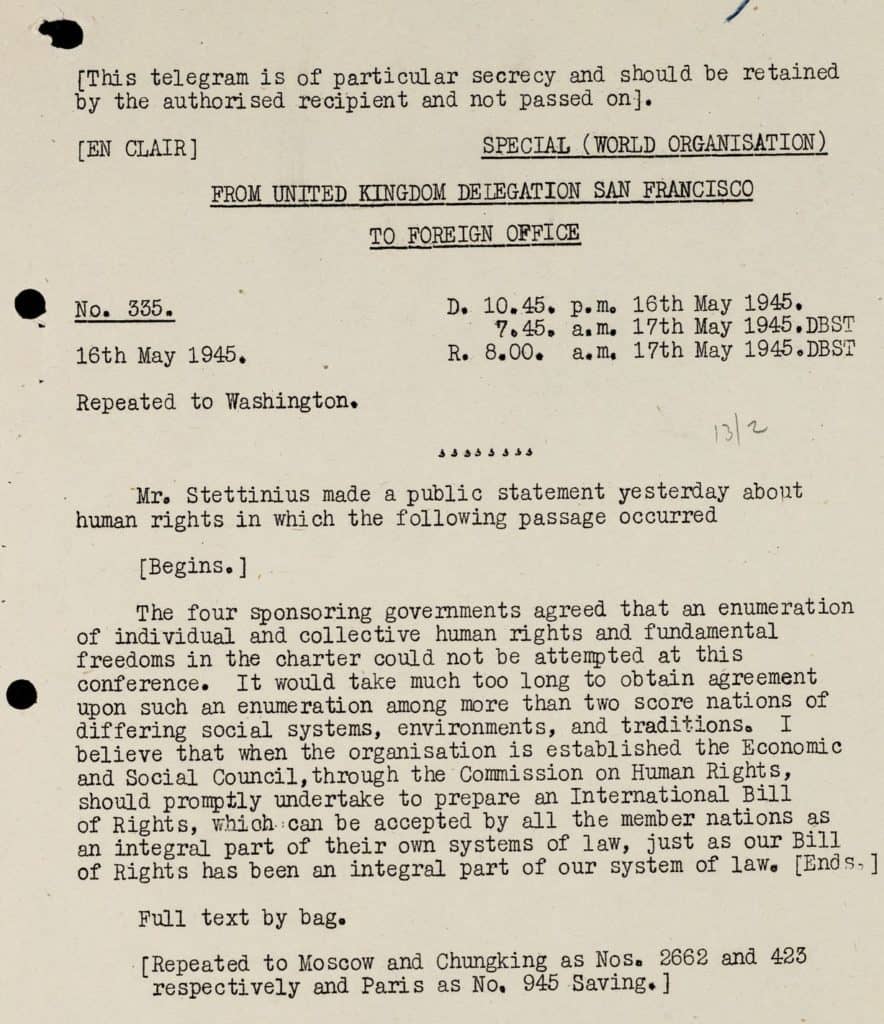

In an age before an email or a tweet could convey on-the-spot information to the world, individuals sent coded telegrams or produced paper reports; bulging files with red stamps changed hands with care and, if the files went far enough and the information was deemed important enough, global policy was changed. These intelligence and security documents are often unique materials which, as well as allowing researchers unparalleled insight into British policy and government, can cast light on the motivations and movements of those people and regions with which the British came into contact.

If you enjoyed reading about Gale’s Twentieth-Century British Intelligence archive, you can read about U.S. Declassified Documents Online in Harry’s post “That’s How an RBMK Reactor Explodes…Lies” – Understanding the Climax of HBO’s Mini-Series “Chernobyl” with Gale Primary Sources and Masaki’s post “U.S. Disavows Apology, Then Signs It” The Pueblo Incident of 1968.