| By Meg Ison, Gale Ambassador at the University of Portsmouth |

The longed-for Christmas break ultimately meant one thing for me as an undergraduate student reading French and History at the University of Portsmouth: January deadlines. Bah humbug! This time last year, as a student studying for an MSc in Social Research methods at the University of Southampton, the festive period was just a short break from terrifying lectures on statistical equations and mind-boggling sociological theory. Now I am a PhD student without looming French grammar tests or the self-imposed pressure to become a Master of Science. (You can read about how myself and social research methods are coming to terms with our differences here). Consequently, I am looking forward to a stress-free build up to the 25th December for the first time in years! Despite my newly found freedom, I am no less academically curious over the festive period. As such, I have enjoyed spending time this vacation delving into the Santa’s grotto that is Gale Primary Sources – overflowing with exciting archives, it is undoubtedly a treasure trove for researchers – to find out how Christmas has been celebrated around the world in history.

Do you hear what I hear?

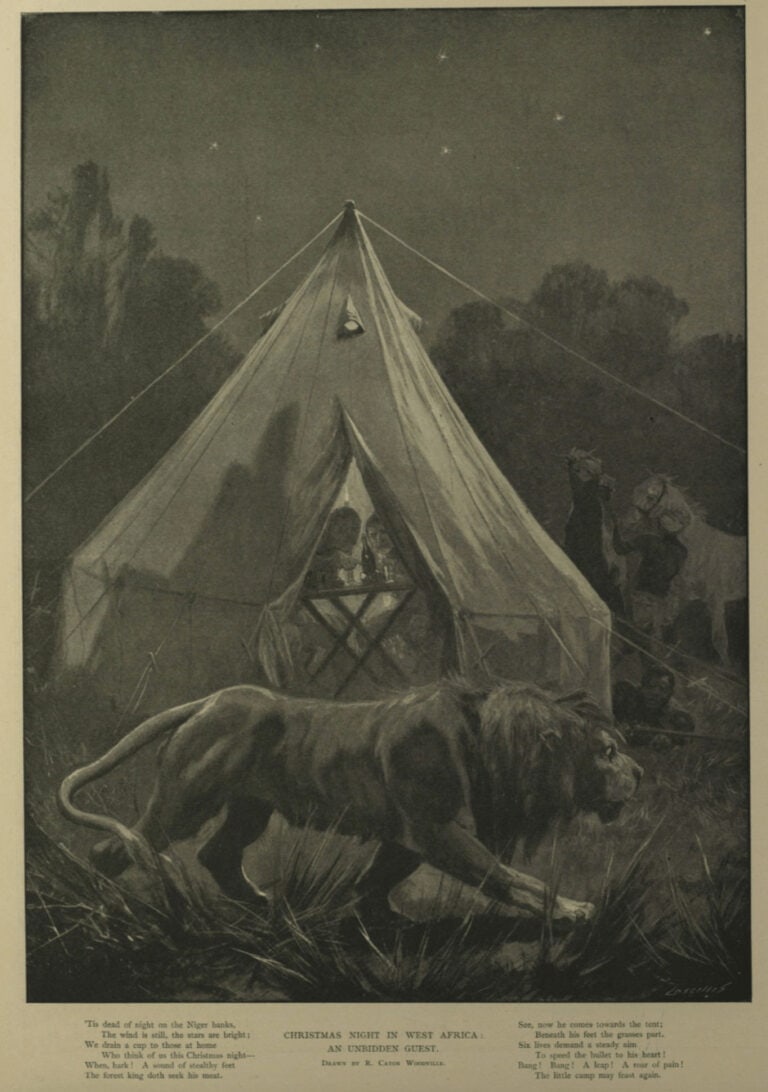

The first stop on our sleigh-ride tour is British colonial West Africa. British poet Clement Clarke Moore had written in 1823 that “not even a mouse was stirring” in his house during The Night Before Christmas. In comparison, on Christmas night 1902, British colonial battle-field artist Caton Woodville was sat in his tent “When hark! A sound of stealthy feet/ The forest king doth seek his meat” – a lion prowled by! Emphasising the exotic was common in colonial travel writing. Nevertheless, spending Christmas amongst hungry lions in Africa at the turn of the century must have been absolutely terrifying!

This thrilling source and many others like it are sat waiting for University of Portsmouth students (and those at many other universities!) to find in the Illustrated London News Historical Archive. This archive is a fantastic resource that covers global political events, as well as quirky stories like that above about an unexpected guest arriving at the Christmas dinner table. It is certainly worth putting aside a little time this Christmas to scroll through the gorgeous illustrations in this archive.

(Not-so) Merry Christmas, Everyone

Jumping back on our sleigh, we can use primary sources to explore other parts of colonial Africa on the 25th December in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Whilst most families have a Scrooge-like uncle or irritating cousins they have to entertain at Christmas, it seems not everyone was as accommodating of unwelcome visitors in times past.

Whilst German soldiers in South West Africa enjoyed decorating a substitute Christmas tree with traditional garlands in 1909 (see below), I found another (likely fictional) narrative printed in the Manchester Times in 1882 which suggested that “in heathen lands…Christmas trees are hung with unfortunate travellers and unappreciated missionaries”. To the modern eye this narrative seems sarcastic and somewhat over-the-top, painting the “Dark Continent” and “heathens” as so sharply contrasting and far inferior to the West – a land epitomised by the beauty and gaiety of a “Christian Christmas” – but these views were also often genuine and proudly expressed.

Whilst scholarly literature tends to focus more on the conventional ways in which colonised Africans tried to subvert colonial rule, such as border hopping to avoid the forced labour draft or refusing to send their children to school, this narrative from a common periodical gives us a glimpse into some of the creative ways in which the imposition of European culture was resisted in colonised Africa. Using Gale Primary Sources to find other off-the-beaten-track primary sources to use in your own work, has great grade-boosting potential for your university essays.

Peace on Earth

Flying far away now from the African continent, the next destination on our tour of 25th December celebrations around the world in history is Europe during the First World War.

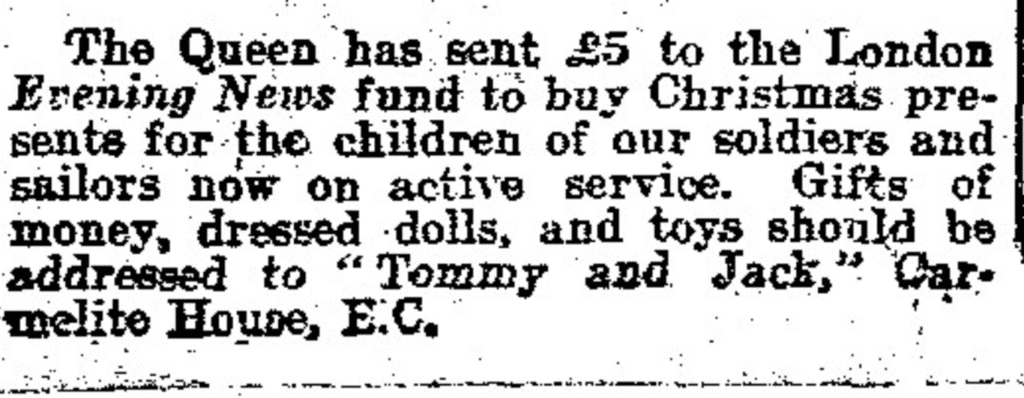

The famous truce between British and German soldiers on Christmas Day has already been researched using Gale Primary Sources (you can check out Kyle Sheldrake’s blog post for The Gale Review here). Less well known is that the British Queen donated money to fund Christmas presents for London children in 1914, whilst their Fathers were fighting overseas in the trenches of France. Despite the war, charity remained a priority during the season of good will.

I was able to find this out by using Gale’s Daily Mail Historical Archive – I wonder what other examples you would find? Why not have a look in the Gale archives yourself and share your findings on our Gale Ambassadors at Portsmouth Facebook page!

God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen

Despite being heralded as the war to end all wars, the First World War was followed by a second in relatively quick historical procession. Our next primary source is another from The Illustrated London News, which demonstrates how British soldiers continued to perform Christian traditions on the 25th December during WWII , despite being stationed in the Libyan desert where the local religion was Islam. Interestingly, the extent to which citizens in faraway lands seek to recreate cultural traditions from home at Christmas time has emerged as a striking aspect of the way in which the 25th December has been celebrated around the world in history.

![Christmas Morning before Bardia: Mass Being Celebrated in the Sands of the Desert by a Catholic Priest and British Soldiers Who Kneel before an Improvised Altar." Illustrated London News, 18 Jan. 1941, p. [65]. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Christmas-around-the-world-christmas-morning-before-bardia-768x503.jpg)

Do they know it’s Christmas time at all?

The forced conscription of colonised Africans into European armies during the First and Second World War is commonly held in historiography as one of the long-term structural causes for the fall of European Empires in Africa. However, despite most French and British former colonies gaining their independence in the 1960s, intrinsic links between Europe and Africa still persist today in many forms, some being more violent than others. You can check out political speeches on postcolonial international relations between Europe and Africa in Chatham House Online Archive.

We have already seen an example of charity at Christmas time, with the source above describing the Queen’s donation to needy children during WWI. However, in the field of International Development today, questions are often raised about whether fundraising campaigns launched by European charities at Christmas time (think Band Aid, for example) are reproducing colonial stereotypes of “backwards” Africa. Anuoluwapo Abosede Durokifa and Edwin Chikata Ijeoma have written an interesting article on neo-colonialism and the Millennium development goals that is worth a read.

Nevertheless, Alex Renton’s 2008 article on Christmas day in Korogocho (a notorious slum in Nairobi, Kenya) that I found in The Times Digital Archive is refreshing, because it sheds light on the ways in which poor African communities look within their own rich cultural heritage to find happiness during the festive period. For example, Kenyan Chapattis are the national equivalent of Christmas dinner in this Nairobian quartier; these “monster crêpes” are “greasy, heavy and strangely delicious if you’re hungry”. Giving gifts of clothes and food before the Church service are also traditions amongst the local community in Korogocho; every woman expects to receive a new dress for Christmas. In most marketplaces during the festive season, there are tailors using old-fashioned sewing machines to stitch vibrantly coloured artificial silks together.

![Renton, Alex. "There won't be snow in Africa this Christmas." Times, 22 Dec. 2008, p. 2[S]+. The Times Digital Archive](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Christmas-around-the-world-what-happens-after-church.jpg)

To me, this quote – “Red, white and green – these are the Christmas colours and the Kenyan colours, too” – sums up the overarching meaning of Christmas that has emerged in this blog post. In the past, as it still is today, celebrating the 25th of December around the world was about celebrating national traditions and a sense of pride in one’s cultural heritage, no matter how far away you are from home or how complicated the circumstances at grassroots level might be.

Gale Primary Sources: the gift that keeps on giving

This tour comes to an end back at our desks. If you are an undergraduate student who has clicked on this post when you should be writing an essay, then don’t fret! Taking regular study breaks does not make you a Master of Procrastination. I cannot stress enough the value of taking regular breaks; they are extremely important for your mental well-being at university and can also be academically stimulating too. By looking up from your textbook to read this Christmas-themed blog post for The Gale Review, you can now return to that essay with ideas and the motivation to make that essay even better by including some yet undiscovered primary sources! (And if you’ve enjoyed staying in the Christmas spirit with this post, how about checking out another during your next study break – ‘The Commercialisation of Christmas’?)

Good luck in your studies and have a great Christmas!