“Every infraction of this order will be punished as treason”: the fallout from newspaper coverage of the ‘Christmas Truce’

Over Christmas in 1914, one of the most extraordinary and civilised moments of the combat on the Western Front happened: the press dubbed it ‘the Christmas Truce’, an event to modern eyes so inexplicable and contradictory to our perceptions of war that it seems it almost cannot be true.

The written accounts that appeared in the newspapers, and the accounts from witnesses and participants present a partisan, if not sympathetic and gentlemanly, portrait of the enemy. On the 1st of January 1915 The Daily Telegraph ran several accounts of the truce from soldiers who had taken part in it, including one from an unnamed soldier serving in the City of London Territorial regiment, who said:

It was a memorable day in our trenches on Christmas Day, as we had a truce with the enemy from eight o’ clock Christmas Eve. Well, it still held good when we left on Boxing Day morning, as not a shot was fired-quite a change, no lead flying about. Truce came about in this way. The Germans started singing and lighting candles about 7:30p.m. Christmas Eve, and one of them challenged any one of us to go across for a bottle of wine. One of our fellows accepted the challenge, and took a big cake to exchange.

We then went half-way to shake hands and exchange greetings with them. There were ten dead Germans in a ditch in front of the trench, and we helped them to bury these, and I could have had a helmet, but I did not fancy taking one off a corpse. They were trapped one night in trying to get at our outpost trench some time ago.

The Germans seem to be very nice chaps, and said they were awfully sick with the war. We were out nearly all day Christmas Day collecting souvenirs.[1]

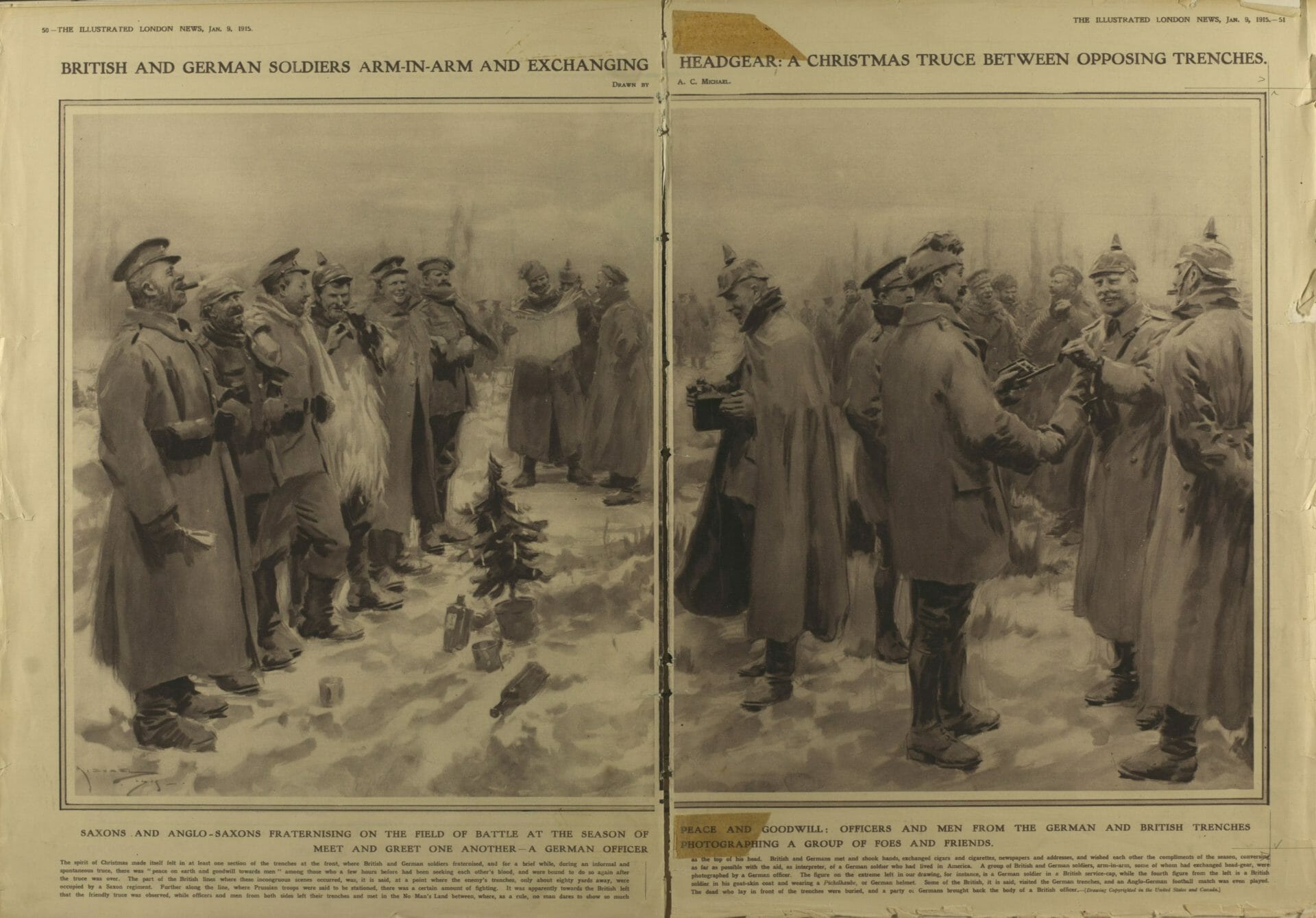

Headlines appeared across the newspapers in the days following the truce, as well as in other popular publications such as the Illustrated London News, which ran illustrations (possibly based on photographs) to accompany their stories.[2]

- The Daily Telegraph (London, England), Friday, January 1, 1915, Issue 18634, p.[6]

- “British and German Soldiers Arm-In-Arm and Exchanging Headgear: A Christmas Truce between Opposing Trenches.” Illustrated London News [London, England] 9 Jan. 1915

- The Daily Telegraph (London, England), Friday, January 1, 1915, Issue 18634, p.[6]

Presenting the enemy in this way hardly helped to cultivate an image that justified the war effort, and the authorities realised they needed to regain control of the information that made it back to the public, when it made it back to them, and in what form. Filtering mechanisms had to be put in place, and a level of censorship and gatekeeping of information had to be introduced, in the interests of public morale and, arguably, to support propaganda efforts. It is difficult to know how extensive the censorship on private correspondence was, but the desired extent of the filtering applied to publicly accessible information is fairly clear from two measures that the military put into action.

One measure was a ban on non-combat engagement with the enemy. The speed of the action taken can be seen in one of the first reports regarding the ban appearing in The Times on 7th January 1915, informing readers that, by Army order, “fraternizing and especially every approach to the enemy in the trenches, is forbidden, and in the future every infraction of this Order will be punished as treason”.

Photography was not exempt from the ban, and the British Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, also threatened Court Marshal for any soldier caught in possession of a privately owned camera.

A second measure was to appoint official war photographers, and transition the visual record from citizen journalism to officially sanctioned representations. The first official war photographer, installed on the Western Front in 1916, was Lieutenant Ernest Brooks, whose remit (along with subsequent official photographers) was to use handheld cameras to take as many photographs as possible. From this, an approved selection was distributed for public consumption, which fitted and supported the message the military and government wished to put across to the public.

It is impossible to know the extent of this auditing process, what percentage of the documents, accounts and photographs made it to the public, and how many were consigned to archives or destroyed. What is clear is that the ‘Christmas Truce’ had set a new goal for the authorities: a more controlled presentation of the war to the British public.

The days of soldiers as a source of information from the front line were coming to an end: it was time for carefully crafted propaganda to take over.

4 The Times (London, England), January 7, 1915, Issue 40745, p.7

5. http://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/photography