│By Dr Lucy Dow, Gale Content Researcher│

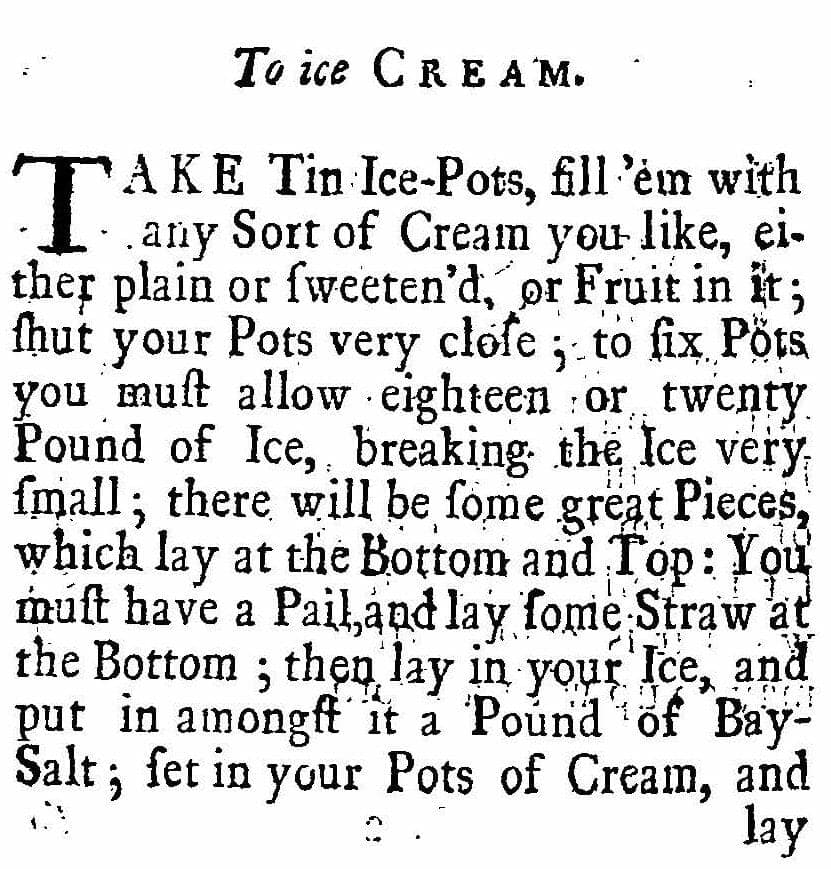

With the weather we’ve seen recently, it is unsurprising that July is national ice cream month! Just search for #nationalicecreammonth on Instagram and you will be inundated with all kinds of delicious (and not-so-delicious) looking icy confections. Whilst you may now be able to get tomato soup, grilled cheese or sushi flavour ice cream, the authors of eighteenth-century English language cookery books tended to stick to more familiar flavours such as strawberry or apricot, although they were not always averse to trying something more unusual. In 1789 Frederick Nutt wrote a recipe (pp. 125-126) for parmesan ice cream! Interestingly, whilst the more exotic chocolate, coffee and even pineapple had made it into ice cream by the late eighteenth century, the now ubiquitous vanilla was still far too exotic and expensive. By exploring eighteenth-century ice cream recipes using Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online we can not only see how ice cream was made, but discover other things these recipes reveal about eighteenth-century life.

![Frederick Nutt, The complete confectioner (London, [1789]), Printed for the author; and sold by J. Mathews, No. 18, Strand, MDCCLXXXIX. [1789]. pp. 125-126 Eighteenth Century Collections Online](https://www.gale.com/intl/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/1.png)

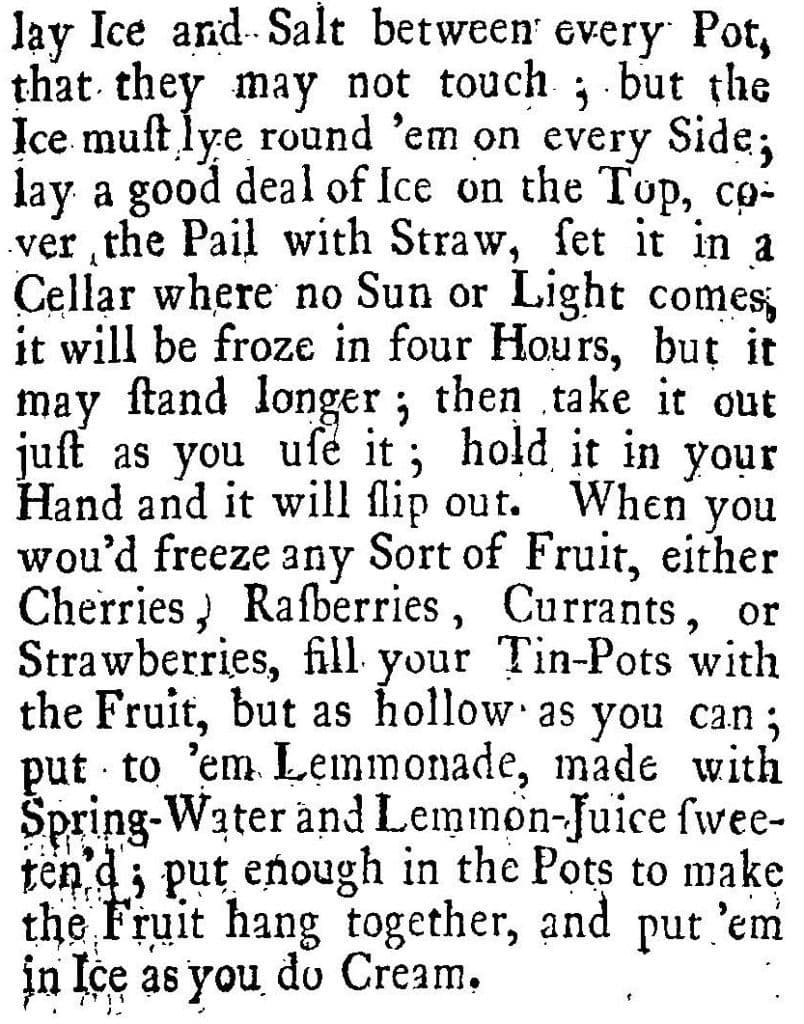

Just as now, making ice cream required some special equipment, however, it was fuelled not by electricity but “elbow grease”! The late eighteenth-century recipe below by Robert Abbot refers to a “freezing pot” (p.79), seemingly a specialist ice-cream making machine. The pot was to be placed in ice and salt, and a churning action applied by the user.

![Abbot, Robert, cook. The housekeeper's valuable present: or, lady's closet companion. Being a new and complete art of preparing confects, according to modern practice. … By Robert Abbot, Late Apprentice to Messrs. Negri & Gunter, Confectioners, in Berkeley Square. [London], [1790?]. (p.79) Eighteenth Century Collections Online.](https://i2.wp.com/www.gale.com/intl/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2.jpg?fit=758%2C1024&ssl=1)

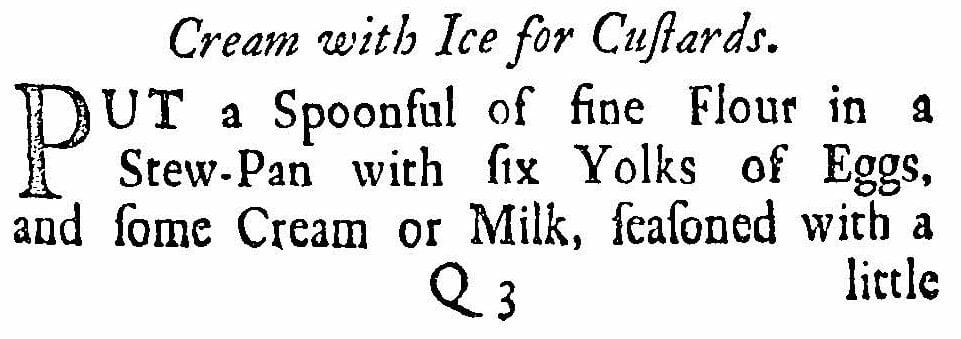

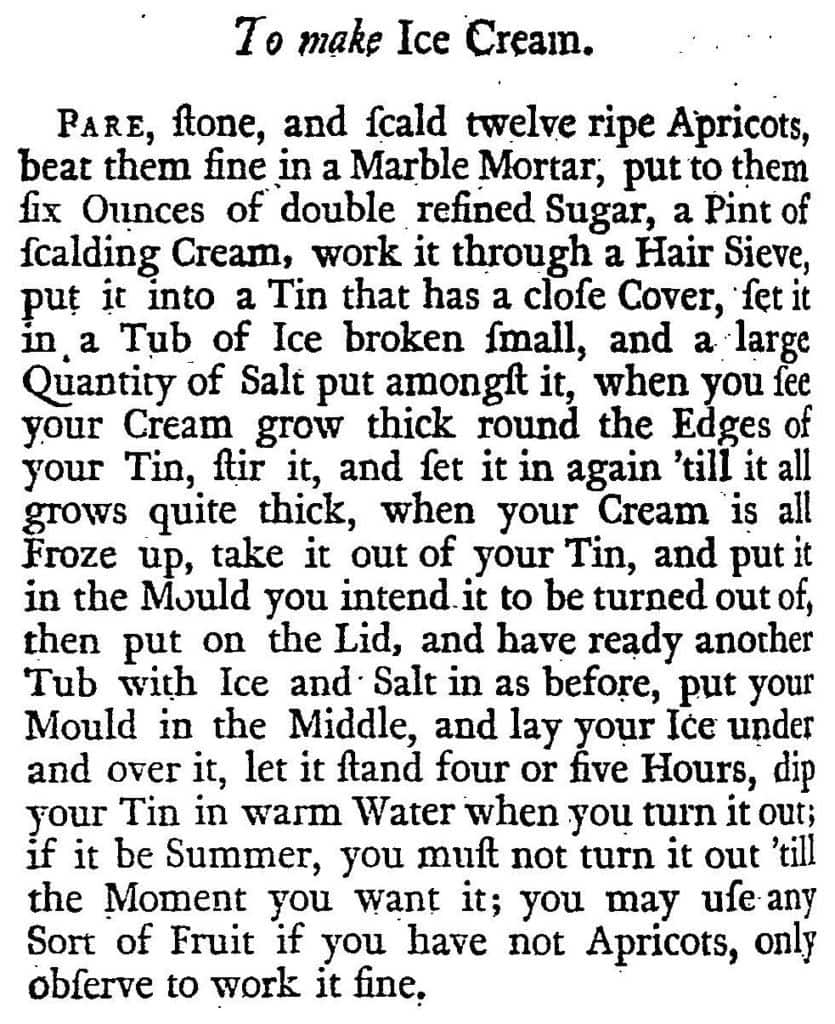

We can trace the development of this nifty sounding bit of kit through older recipes for ice cream. Mary Eales’ 1718 recipe for ice cream contains very detailed instructions (pp. 92-93) about how to ice the cream mixture:

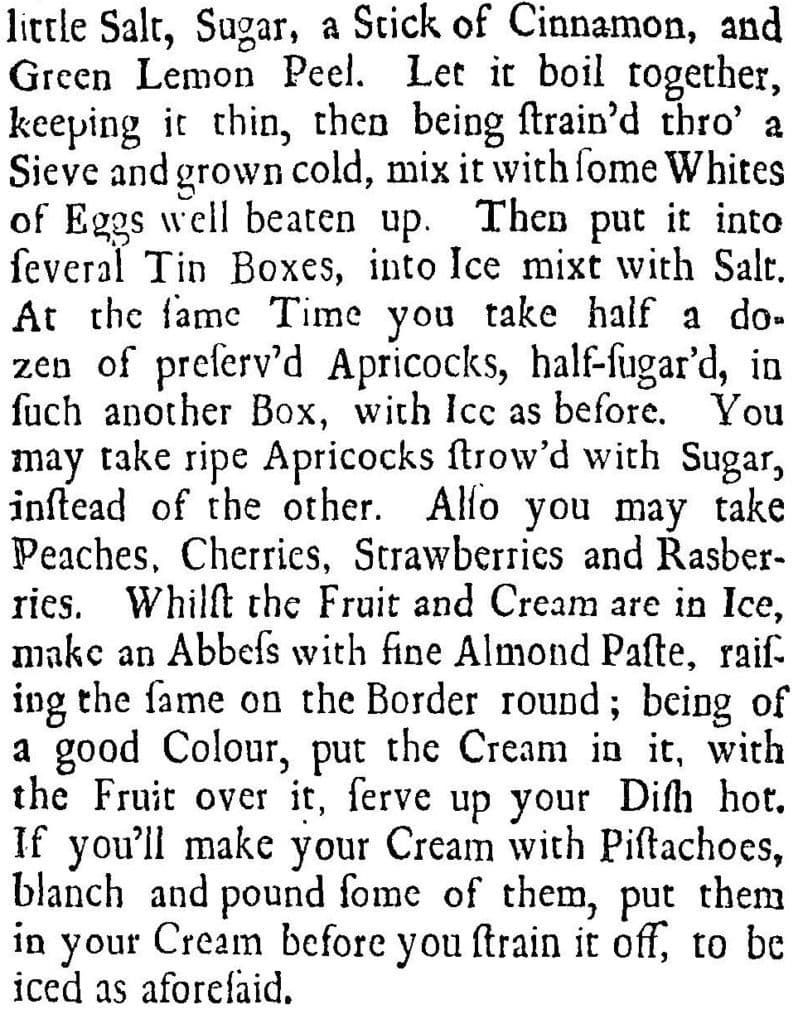

This would not be ice cream as you or I know it. Without any churning to incorporate air into the mixture, it would essentially have been a solid block of frozen cream, albeit flavoured. By the 1730s Vincent La Chapelle, one of the great court cooks of the century, was adding in whipped up egg white to lighten the mixture (pp. 229-230), but this still would have been a fairly solid concoction by modern standards.

By the 1760s, Hannah Glasse, in her second, less-successful work, The compleat confectioner, was recommending at least one churning of the frozen mixture (pp. 161-162). However, it is in Elizabeth Raffald’s 1769 work that a regular churning technique is first suggested (p. 228), which would have made the ice cream much more aerated than any of the previous recipes.

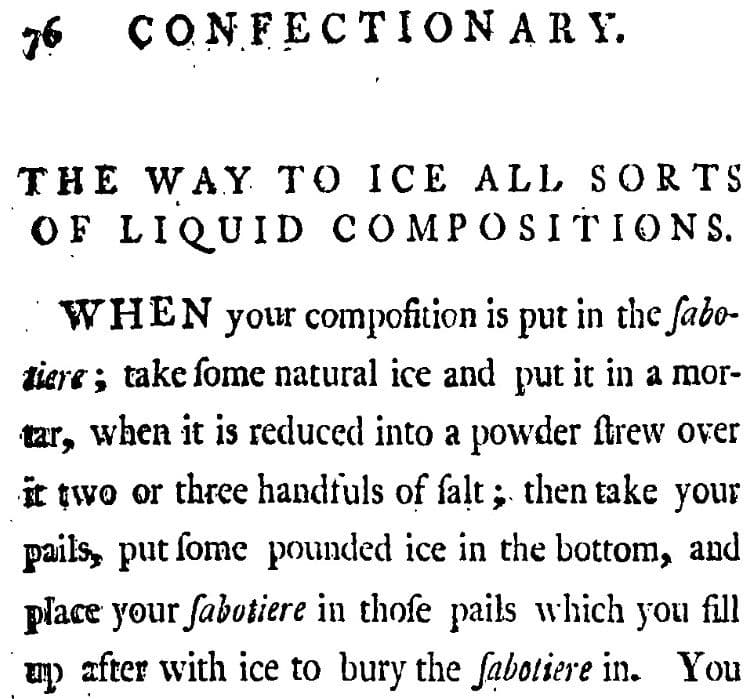

Mr Borella in 1770 takes care to give detailed instruction about the churning process. He explains that the delicacy of the ice depends on the scraping and mixing of the liquid as it freezes. His many ice cream recipes make reference to a specialist piece of equipment called a sabotier (p. 76). The use of this kind of specialist equipment has echo in the version of Glasse’s recipe found in the 1775 work of Elizabeth Clifton. Whereas Glasse requires her reader to have two pewter basins, one smaller than the other and the small one with a close cover, Clifton talks of two pewter basins “which are made for that purpose by pewterers”. This is, presumably, what comes to be known as a “freezing pot” by the time Abbot was writing in 1790.

The development of this specialist equipment over the course of the eighteenth century aligns with the wider changes in material culture that were experienced over the period. All kinds of new household goods were emerging, of increasing specification, for elite and middling households. The development of the freezing pot, and associated items such as ice moulds and ice cream pails, exemplifies this change.

Blog Post Cover image citation: Image obtained from Unsplash online depository, link to image: https://unsplash.com/photos/pcvE-o4zCwM, Terms and conditions: https://unsplash.com/terms