│By Masaki Morisawa, Senior Product Manager, Gale Japan│

One of the great things about Gale Primary Sources is the serendipity – the unexpected discoveries you make when you were looking for one thing, and stumble on something totally different yet fascinating. While I was searching for material to use in my blog post about the Paris International Exposition of 1867, I made a quirky discovery. That blog post was about Tokugawa Akitake, the teenage half-brother of the Shogun of Japan, who came to Paris with his retinue in 1867 in order to exhibit at the Exposition and mingle with various European sovereigns. I was typing broad keywords into Gale Primary Sources, such as “Japanese” and “Paris,” with a date limiter of 1867. Sure enough, the cross-search platform returned newspaper articles that were obviously related to my topic, such as:

However, as I scrolled down the results, I also encountered multiple references to “Japanese Jugglers” from the same period, especially from American sources:

This seemed strange! In 1867, Japan was still very much an isolated nation whose people almost never left the country. Even for a top-ranked elite such as Akitake, a trip to Europe was an extraordinary event, even more so for commoners – and why jugglers?

While the jugglers aroused my interest, I wanted to finish my Paris Exposition post, so I refused to give them much thought and concentrated instead on articles related to Tokugawa Akitake. But, like mischievous elves, the jugglers would sneak into view again, as in the passage below describing the Exposition’s opening ceremonies. “To the barbarian eyes of any Londoner,” the article says, Akitake and his train “would seem identical with the troop of jugglers who lately performed the butterfly trick in St. Martin’s hall.”

Who were these jugglers, who supposedly came to London before Akitake, in a time when hardly any Japanese travelled abroad and were apparently so popular that “any Londoner” would remember them? Were they really Japanese, or some sort of bogus team posing as Orientals?

—And what on earth is the butterfly trick?

Unable to contain my curiosity any longer, I decided to take a slight detour from writing my post and ran a search on both “butterfly trick” and “Japanese”. The search returned a whopping 211(!) articles from 1867, many of them hyped-up ads and raving reviews from both sides of the Atlantic, including this one from The Illustrated London News:

Well they do look like my countrymen from 150 years ago. And the picture on the left is the “butterfly trick,” where the juggler “makes little paper butterflies and keeps them hovering in the air by the wind of a pair of fans, causing them to fly to and fro at his pleasure … seemingly with the easy motions of life.” (For those interested, here is a YouTube video of a modern Japanese performer re-enacting this type of performance.)

I also found an article from an American children’s magazine which gives detailed instructions on how, “with a little skill and perseverance,” every boy may acquire the famed butterfly trick that has “delighted thousands”.

A full-text search on “Japanese jugglers” in Gale Primary Sources returns more than 2,700 articles from various periods, and when mapped on the Term Frequency tool, there is a clear and sudden peak in the year 1867, after which it declines quickly, and apart from a moderate revival around the 1890s, almost completely dies out by the early twentieth century.

While at the time I resisted the urge to deviate further and eventually finished my Paris Exposition piece, the image of a top knotted Japanese in kimono garb wowing British and American crowds by floating paper butterflies with his fan never quite left me. Later, I continued to poke around our archives and the web for more information. Eventually, the answer came in the form of an excellent book by Frederik L. Schodt entitled Professor Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe.1 The author is a well-known translator and writer of Japanese popular culture, and he too had been intrigued by the same questions as I when he came across obscure references to Japanese jugglers from the mid-nineteenth century. He travelled to various archives and used digitised historical newspapers and magazines to research this phenomenon, gradually piecing bits of information together to recreate the extraordinary story of an American acrobat and entrepreneur, Professor Risley and his Imperial Japanese Troupe.

While for details I would refer readers to Schodt’s immensely readable and fascinating book, briefly, the “Imperial Japanese Troupe” was born when the globe-trotting American acrobat and impresario Professor Risley contracted a group of eighteen traditional Japanese performers during a stint in Yokohama. The troupe crossed the Pacific with Risley, and first performed in San Francisco on January 1867, to great acclaim. They then toured the East Coast from Philadelphia, New York and on to Washington, D.C., where they even had an audience with the U.S. President Andrew Johnson:

Like all such circus acts, they made a strong impression on children, too, as evidenced by the article I mentioned previously from Frank Leslie’s Boys of America, as well as this adorable cartoon from Harper’s Weekly:

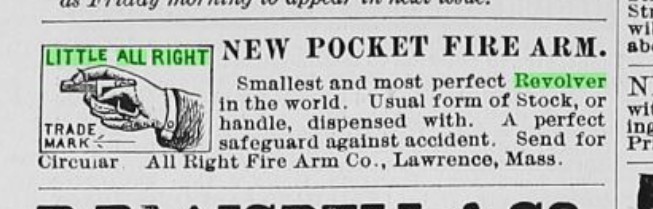

Risley’s troupe had a star in the child performer Hamaikari Sadakichi, or “Little All Right,” as he was endearingly nicknamed by the Americans as he would shout the English phrase “all right!” at the conclusion of each stunt. He became so famous that he became the subject of a song, the “All Right Polka,” and a firearms manufacturer created a pocket revolver named after him. 2

And when Little All Right suffered a stage fall in June 1867, the news of his accident “spread like wildfire across America through telegraph and newspaper.” 3 In Gale Primary Sources one can easily find many punning headlines like this one:

While Risley was clearly the pioneer, his was not the only Japanese troupe to perform overseas, as his success inspired many imitators who brought similar performers from Japan to America and Europe, to cash in on the boom he helped create. Such travels were not without risk, however, and when the leader of one such rival troupe, Hayatake Torakichi, died suddenly in New York, his funeral was widely reported in the U.S.:

!["The Funeral Solemnities of Hay-Yah-Ta-Ker." Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper [New York, New York] 29 Feb. 1868. Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers](https://i2.wp.com/www.gale.com/intl/blog/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/NCNP-Death-of-Hayatake-GT3012579777.jpg?fit=704%2C1024&ssl=1)

Riding on the momentum of their American success, in July 1867, Risley and the Imperial Japanese Troupe made the long journey across the Atlantic to bring their astonishing act to the Old World, starting in Paris to perform during the Exposition. From there, they conquered one European city after another, from Lyon to Birmingham, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, The Hague, Utrecht, Leiden, Antwerp, London, Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Seville, Lisbon, Porto and Le Havre – crossing the English Channel three times in between. (It was their visit to London that was captured in the aforementioned Illustrated London News article.)

They then sailed back to New York for a final stint there, before the members of the group split, nine of them electing to stay with Risley for further adventures, the remaining eight (one of them, unfortunately, had died of an illness in London) making the long journey back to Japan. They arrived at Yokohama in March 1869. Perhaps to their astonishment, they had arrived back in a country in the midst of a momentous transformation from an isolationist feudal nation under the Tokugawa Shogunate to a modernised nation ruled by the newly enacted Meiji Government. 4

So, what began as strange “noise” in my search results on a better-known figure (Tokugawa Akitake) accidentally introduced me to the fascinating, yet unsung, adventure by a group of common entertainers, whose great fame and success in the West exceeded, however briefly, that of any other Japanese figure of the period. Although I was aided greatly by Frederick L. Schodt’s book in making sense of it all, this little adventure of mine wouldn’t have started without that little bit of serendipity in Gale Primary Sources. That to me is the great thing about historical newspapers; the way they shed light, often in an unexpected way, on obscure stories and events that captured the imagination of common people of the time.

“The second thing that made this book possible is new technology. … I was greatly aided by the development of online databases of scanned nineteenth-century newspapers and magazines that have recently become available to researchers. … In a sense, online databases are rather like the new satellite, sonar, and undersea robotic technologies that have made the world’s oceans increasingly transparent, allowing discovery of more and more valuable treasures and old wrecks hitherto hidden beneath the sea.” 5