│By Karen Harker, Gale Ambassador at the University of Birmingham│

Anyone familiar with Gale Primary Sources knows that it provides archival access to major periodicals such as The Times, The Daily Mail, The Financial Times, and The Economist. The longevity and sustained popularity of these publications mean that they are often the first place a student or researcher might look for information on a historical topic, but it is worth remembering that a vast majority of the articles found in these newspapers are written by white, heterosexual, cisgender men. This is particularly true of anything published in the eighteenth, nineteenth, and early twentieth centuries. Even as women, people of colour and members of the LGBT+ community are increasingly employed by these newspapers, their contributions still exist in a notable and significant minority. While these newspapers are fantastic resources, they often only tell one side of the story.

So, where might one go to read the writings of minority voices and hear the other side of the story? After a little digging in Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender, I found several amateur journals, magazines and newsletters written in the United States in the midst of various liberation movements during the 1970s and ’80s, including the Women’s Liberation Movement, Black Power Movement, and Equal Rights Movement, which fought for LGBT+ equality. These publications were often spearheaded by small groups of like-minded individuals looking for a safe place where they could express their views and form a community fighting for a cause.

Serving as a vital outlet for under-represented and marginalised groups, these publications offer researchers a unique insight into the lives of some individuals behind these movements. We can read their stories, poetry and essays, see their art and illustrations and – through these expressions – witness their near-constant struggles against oppression, and the tenacity with which they fought for change. The decoupage-like layouts of their publications, often with handwritten headlines and hand-drawn images, are a testament to their commitment to creating and publishing despite financial, social, political and cultural barriers.

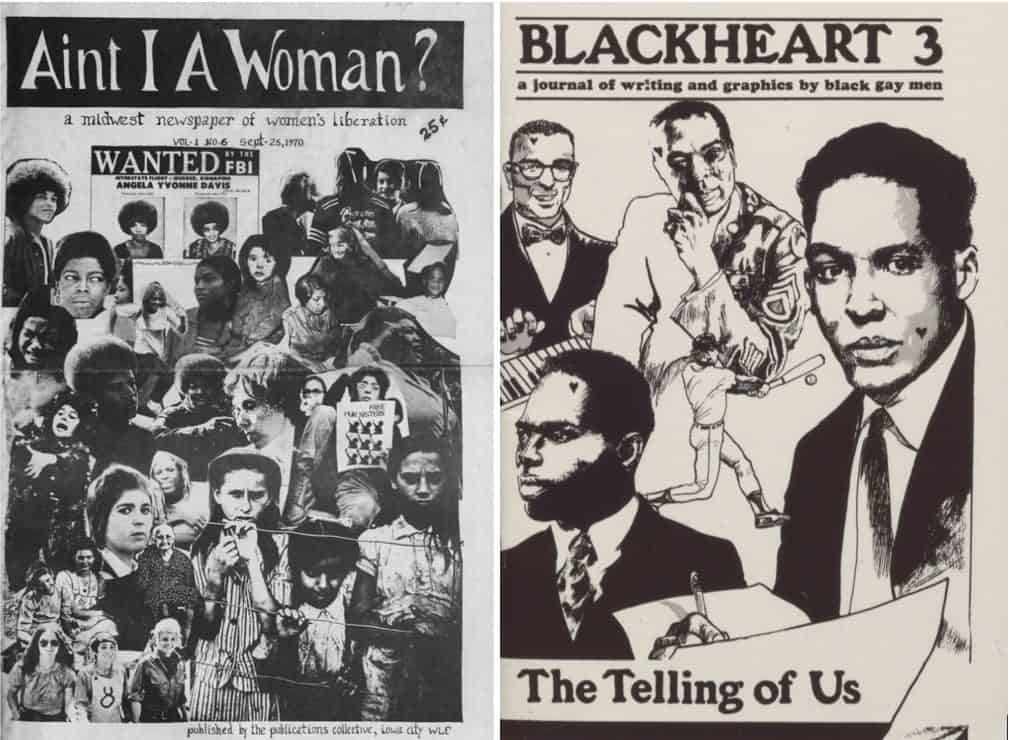

There are dozens of publications like this accessible through Gale, but here I discuss the two that really stood out to me during my research: Ain’t I a Woman?: A Midwest newspaper of women’s liberation published by a group of ten women in Iowa City, Iowa, during the 1970s and Blackheart: A journal of writing and graphics by black gay men published by a group of gay, black men in New York City in the 1970s and ’80s.

Ain’t I a Woman?: A Midwest newspaper of women’s liberation

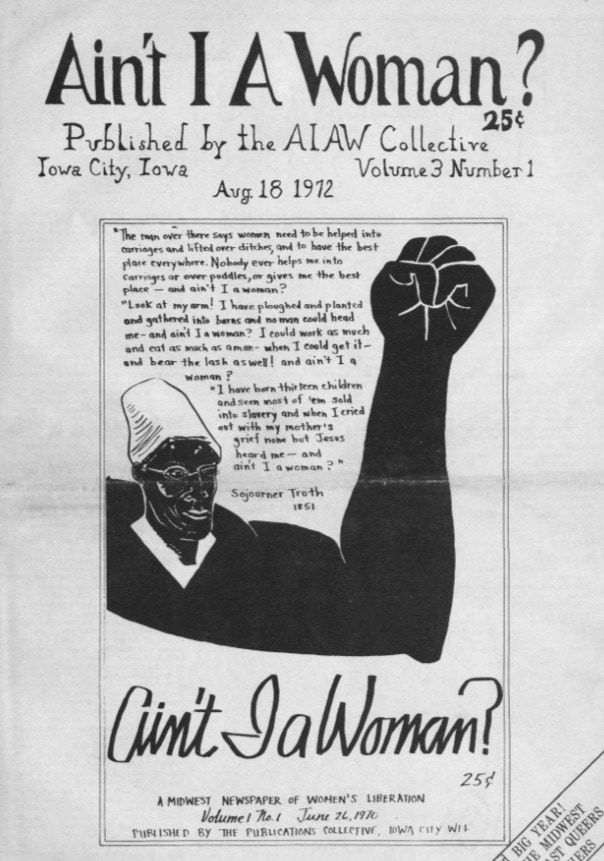

Ain’t I a Woman? shares its name with the poem written in 1851 by Sojourner Truth, former slave, abolitionist, and civil and women’s rights activist. Her picture and poem (hand-drawn, of course) are included in every edition of the newspaper, usually accompanied by a large, flexed arm with a closed fist representing strength and resilience.

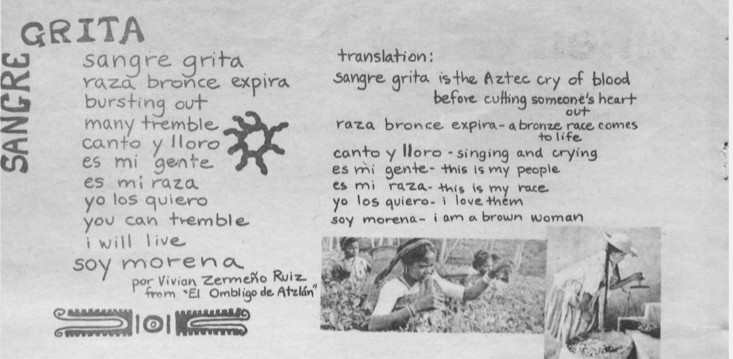

This self-published newspaper contains a variety of content, ranging from essays and poetry by women from all over the US, to information about obtaining affordable childcare, fighting for equality for lesbians and bisexual women, challenging gender roles, and female reproductive rights. One of the most laudable aspects of the newspaper is its awareness about class and racial representation. Many publications that came out of the Women’s Liberation Movement were mostly aimed at white, middle-class women, but Ain’t I a Woman? addresses issues that applied to women from various socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds. The May 1974 bilingual issue shows an awareness for the non-white and non-English speaking women fighting for liberation, containing, among other articles, the poem pictured below by Vivian Zermeño Ruiz in both Spanish and English.

The August 1972 edition of the newspaper addresses issues of class and identity within the feminist movement. It contains an article that emphasises “why economic class is a vital Feminist issue” and seeks to mobilise and unify women through “concrete political goals”. Other editions provide sex education for women who may have not had any, discussing the female anatomy, menstruation, pregnancy, menopause and abortion procedures. In an age before quick internet searches, this was valuable information for women who may not have the money to see a doctor or had received little education about their reproductive systems and rights.

Ain’t I A Woman? repeatedly advocates for women who were victims of rape, sexual assault and domestic violence, providing literature and other points of contact that might help victims to receive counselling, medical attention, legal aid or support from battered women’s shelters. The efforts of the publication seem to be best summarised by this statement by an anonymous contributor in the September 1970 issue:

“We must push back oppression, all together. We all feel it and our unity give each of us its strength … goodbye, goodbye forever, counterfeit Left … Women are the real Left. We are rising, powerful in our unclean bodies; bright glowing made in our inferior brains; wild hair flying, wild eyes staring, wild voices keening; … tears in our eyes and bitterness in our mouths for children we couldn’t have, or couldn’t not have, or didn’t want, or didn’t want yet, or wanted and had in this place and this time of horror. We are rising with a fury older and potentially greater than any force in history, and this time we will be free or no one will survive. Power to all the people or to none.”

Blackheart: A journal of writing and graphics by black gay men

Like Ain’t I A Woman?, the aim of Blackheart was to share the stories of underrepresented people. Each issue features a collection of writing – fiction, nonfiction, poetry and drama – and graphics created by gay, black men in and around New York City. As the journal’s managing editor and president wrote in the third iteration of the journal:

“Blackheart has always been about encouraging black gay writers to write about their lives. Previously, most black gay writers, or any black gay artists for that matter, have for various reasons lived their creative lives solely through the experience of another’s language. Because of hetero-sexism and racism, our lives are not considered worthy of examination in the arts … Blackheart is, hopefully, part of a process that will encourage more of us to record our feelings and lives.”

Most of the content tells stories. We learn about families, relationships, loves, communities, joys, and struggles through these skilfully and passionately written narratives. The journal also addresses issues central to the black and gay communities. Some of these essays, written thirty to forty years ago, are sadly still relevant today, as the fight for true equality continues for African Americans and people of the LBGT+ community.

An essay written by Joseph Beam addresses the lack of representation of black and gay men in professional communities and the inaction of white men in the fight for racial equality. Beam points out the difference between merely discussing racism and actually taking action against the systems and people which help to sustain it. In the final paragraph of his essay, he states:

“How much longer will most white men continue to be committed to discussing rather than changing those thoughts, feelings, and institutions that maintain racism? Racism is not my responsibility as a man of color; my hands are full just trying to get through my day (I am always perceived as moron, thief and rapist). You extend your right hand in friendship, and sucker-punch with the left. With eyes red and swollen, from too many tears and too many punches, I focus on other men of color as we begin working on the racism we have internalized, working through the contempt, the anger, the fear with which we greet each other.”

Here, he sums up a lesson many of us with privilege – racial, class, or another – still seem to be learning today: it is not the responsibility of the oppressed to educate the oppressor.

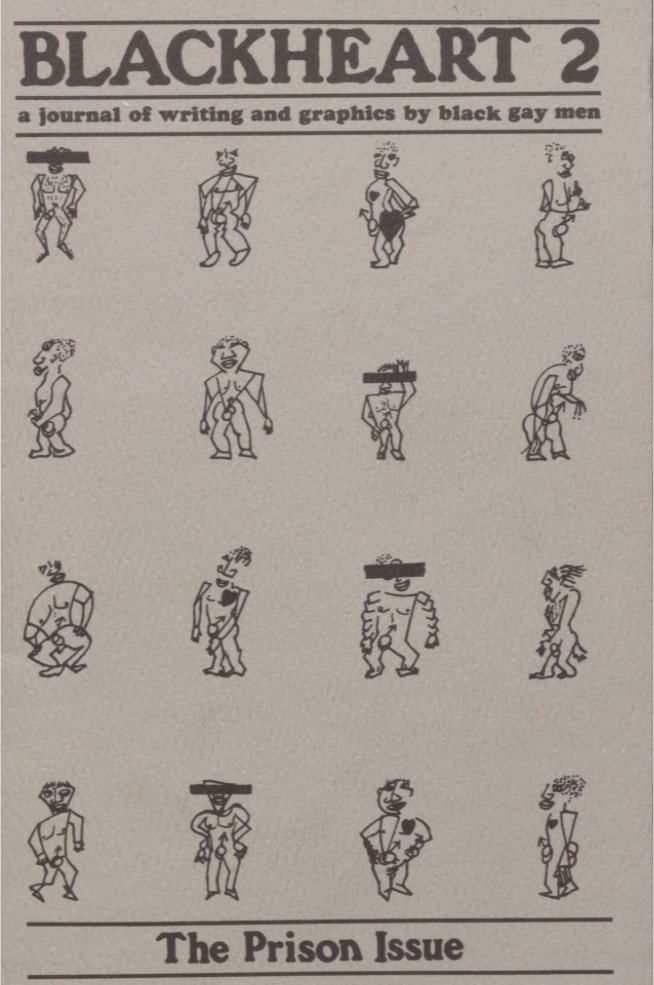

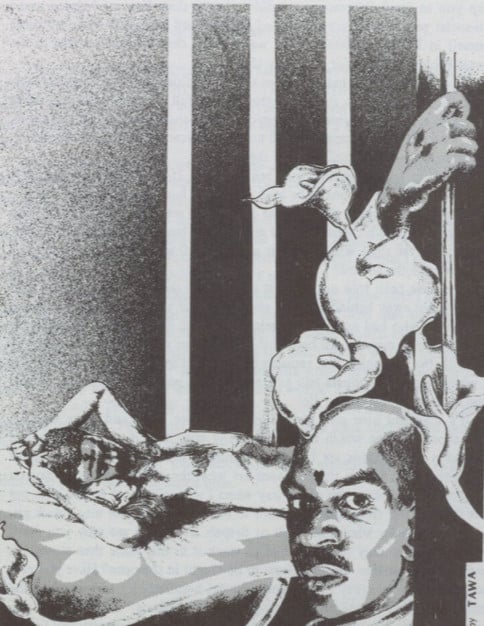

The second edition of Blackheart, published in 1984, is a special prison issue which features the writing and illustrations of incarcerated, black, gay men. As the cover (designed by Armando Alleyne) illustrates, one in four black men in America spends some part of their lives in jail or prison, a rate much higher than that of white men. This disparity and the systemic racial prejudice which underlies the American prison system is discussed frankly and openly. Parallels are drawn between the forced enslavement of black people and the continued mass incarceration of black men, particularly in Antony Q. Cursor’s article “Invisible and Visible”. The piece opens with this quote from Sundiata Acoli:

“Most blacks were originally brought to America as prisoners, slaves in the first place, held captive against their will as prisoners. The primary concern of all prisoners is ‘gaining their freedom’. As America changed from a colony of England to the foremost Imperialistic power today, the forms of imprisonment of blacks changed accordingly – but imprisoned we remain – in the ghetto colonies, in poverty, in dependency, in jails and penitentiaries…”

“Blackheart 2.” Blackheart: A Journal of Writing and Graphics by Black Gay Men, 1984. Archives of Sexuality & Gender http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/WXSBUJ372336002/GDCS?u=bham_uk&sid=GDCS&xid=a5521021

This issue also contained deeply personal writings and illustrations of inmates, providing a safe space where they could express themselves and tell their stories. Life behind bars for anyone can be difficult, but as the introduction to the journal points out, it can be even harder to navigate prison life as a gay man:

“In some prisons, gays are victimized and sexually harassed; in others it’s possible for town men to be lovers and for this to be quietly condoned by the authorities. In some places coming out is a possibility, while in others it would place your life in danger. From the material that we received, it’s possible for us to make only one general statement: for most black gay prisoners, incredible loneliness and isolation is the rule.”

That Blackheart offered a small outlet for these men is an incredible gift, both to the contributors who shared their art and for those of us who get to read it.

“Blackheart 2.” Blackheart: A Journal of Writing and Graphics by Black Gay Men, 1984. Archives of Sexuality & Gender http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/WXSBUJ372336002/GDCS?u=bham_uk&sid=GDCS&xid=a5521021

Blackheart also addresses a social issue still relevant to modern society: police brutality and excessive force, often aimed at black men. In 1983, Michael Stewart, a black man who worked as a busboy in the gay-owned and operated Pyramid Club, was murdered by New York City transit police. The story of his death was highly debated and publicised at the time, much like the recent murders of young, black men by police in America such as Stephon Clark, Antwon Rose and Emantic Bradford Jr. 1

The current statistics are harrowing, as they reveal how the story of Michael Stewart in 1983 has repeated itself far too many times since in American society. In 2018 alone, police killed 1,164 people, and 25 percent of those people were black, despite making up only 13 percent of the population.2 Black people are three times more likely to be killed by police than white people, and 30 percent of those killed in 2015 were unarmed.3 In only one percent of these cases are the officers involved actually convicted or held accountable. 4 The officers who murdered Michael Stewart were, unsurprisingly, not held accountable for their actions, but Isaac Jackson’s poem about Stewart ensures that we do not forget his name or his story.

Why we should not overlook amateur publications

While it might be easy to overlook amateur publications such as Ain’t I a Woman? and Blackheart, what they offer to students and researchers is an insight into the lives and struggles of oppressed minorities. They provide an incredible opportunity to read the words of real people involved in the grassroots activism that inspired so much of the feminist, civil rights, and LBGT+ equality movements, rather than merely reading an article, feature or editorial from a major news source. In these stories, we see reflections of our own deeply flawed societies; societies in which homophobia, racism, and sexism are still rampant. This is depressing in some sense, but reading these stories can also serve as a catalyst for further activism today. From pushing for female reproductive rights to ending police brutality, from addressing the mass incarceration of black men to providing basic human rights to the LGBT+ community, we still have a lot of work to do. Let’s take inspiration from the brave, tenacious souls who gave us Ain’t I a Woman? and Blackheart and see if we can make a change.

Blog post cover image citation:

Left Cover for Ain’t I a Woman?, Vol. 1, no. 6. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/ZUOVWU043445773/GDCS?u=bham_uk&sid=GDCS&xid=91d72133,

Right Cover for Blackheart, Vol. 3. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/DIEPIR707693510/GDCS?u=bham_uk&sid=GDCS&xid=2668f2ee

- Michael Harriot. “Here’s How Many People Police Killed in 2018”. The Root. 1 January 2019. https://www.theroot.com/here-s-how-many-people-police-killed-in-2018-1831469528

- See statistics on https://mappingpoliceviolence.org

- Ibid.

- Ibid.