By Calvin Liu, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford

‘April is the cruellest month’, so went the ominous opening line of T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Perhaps. But the first day of April, at the very least, has been witness to some of history’s biggest public hoaxes – many of which are hilarious and cruel in equal measures. From the Victorian “Grand Exhibition of Donkeys” in 1864 to the 1957 BBC documentary on spaghetti-bearing trees, these moments of meticulously organised journalistic foibles harken back to a now bygone age before the rise of wide-spread corporate PR-stunts and instantaneous internet trolling. The abundance of April-fool’s-related material in the Gale archives sheds light on the long history of a yearly occasion that stretches as far back as the time of Chaucer, who slyly alludes to the day as the ‘thirty-second of March’ in The Nun’s Priest’s Tale (a story of a farmer tricked into a singing contest against a fox) as early as the 1300s.

Some of the earlier Victorian sources utilise the occasion of April Fools as a tool for social commentary. For instance, this 1843 issue of Cleave’s London Satirist and Gazette of Variety, a minor publication started by the members of the Working Men’s Association and now found in 19th Century UK Periodicals, uses the punch line of ‘Do you take me as an April Fool?’ in a series of cartoons showing the wealthy shrugging off requests from the poor.

In one of these cartoons a ‘Poor Woman’ begs, on her family’s behalf not to be evicted from their house, whilst the landlord looks back and quips ‘Woman – do you take me for an April Fool?’ Another shows a snarky rector astounded and offended by a request for him to ‘preach a sermon for the benefits of poor people, and do it for nothing! By the smell of my dinner, you must take me for an April Fool!’

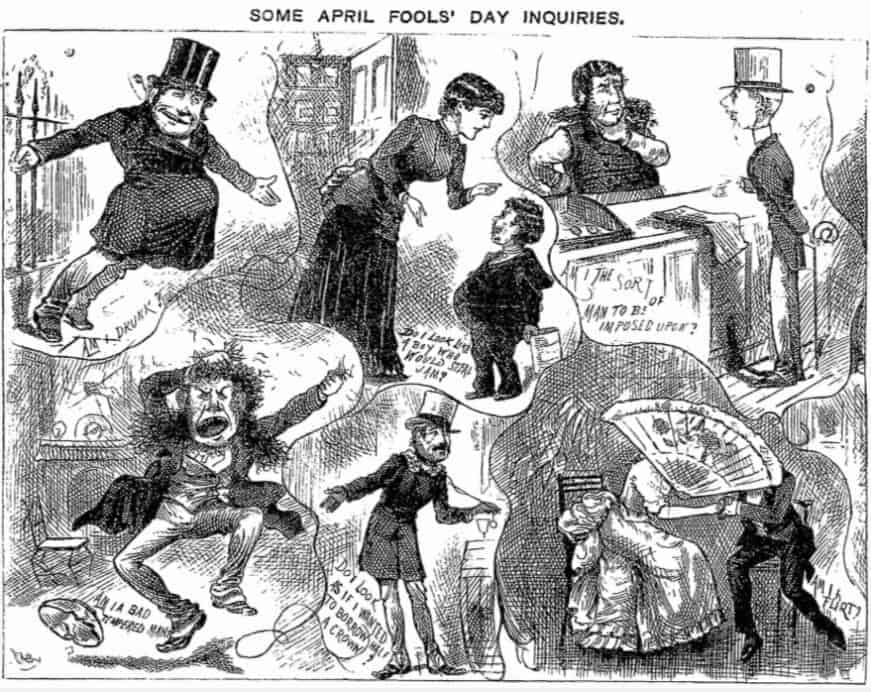

Similarly in the April 1885 issue of Funny Folks, a cartoon titled ‘Some April Fool’s Inquiries’ satirises the middleclass lack of self-awareness at the time. The bottom left corner of the cartoon depicts an apish-looking man, jumping from the ground furiously whilst asking ‘Am I a bad tempered man?’ Two other figures, both in top hats, ask if they’re ‘the sort of man to be imposed upon?’ and if they looked like they ‘wanted to borrow half a crown?’

It’s interesting that many of these Victorian sources have made use of the occasion of April Fool’s Day as a time for collective reflection as well as individual self-questioning. The very concept of a day dedicated to outlandish hoaxes and pranks has lent itself quite well to the ideation of seemingly farfetched notions such as social reform and universal welfare.

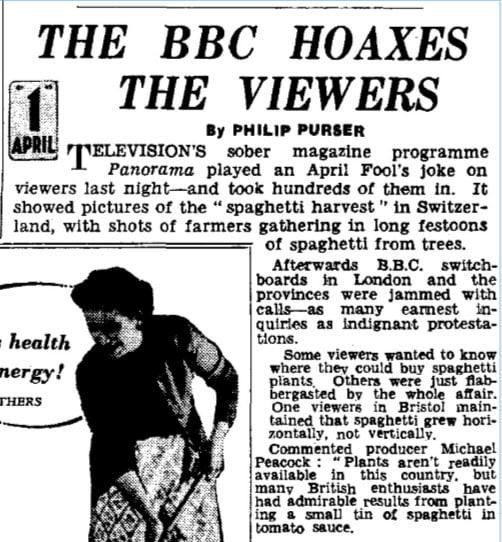

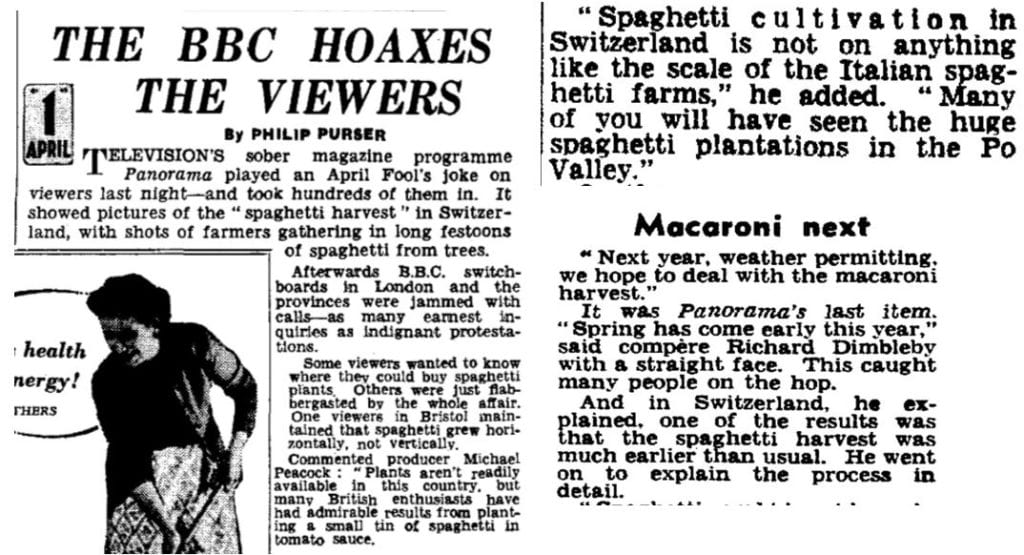

In more recent times, the Daily Mail reported in vivid detail on the 2nd of April, 1957, the public response to the BBC’s programme about the ‘Spaghetti Harvest’ which had aired the day before. In the now notorious BBC Panorama report, a sober and serious voice narrates that ‘the last two weeks of March are an anxious time for the Spaghetti farmer,’ whilst commenting on the wider commercial networks surrounding the cooked-up specimen:

‘Spaghetti cultivation here in Switzerland is of course not carried out on anything like the tremendous scale of the Italian industry […] many of you I’m sure have seen pictures of the vast Spaghetti plantations in the Po valley’.

The day after the programme aired, the Daily Mail reported:

‘Some viewers wanted to know where they could buy spaghetti plants. Others were just flabbergasted by the whole affair. One viewer in Bristol maintained that spaghetti grew horizontally, not vertically.’

The paper even managed to get in touch with the producers of the programme, who replied that the plant was, regrettably, not available in the UK, though enthusiasts have had ‘admirable results’ from planting small tins of spaghetti in tomato sauce. The report ends with a promise from the programme creators that ‘Next year, weather permitting, we hope to deal with the macaroni harvest’. Very sadly, this pledge has yet to be fulfilled as of 2019, and members of the public have had to resort to the local variant of supermarket-bought pasta in the meantime.

These examples of April Fool’s hoaxes taken from Gale’s historical journalism archives represent only a selection of the diverse range of subjects covered and slants taken by the media throughout the years. From the Victorian debates surrounding social reform, to worries about material shortages during the post-war years, focalised in the ‘Spaghetti Harvest’, these seemingly immaterial April Fool’s hoaxes give us an insight into the underlying anxieties of their respective generations – albeit distorted through the lens of journalistic jest. They also emphasise the value of using apparently more peripheral historical sources – and the more holistic view of the past that they can provide.

Want to read more about April Fool’s Day hoaxes in the media? Check out a previous blog post on The Gale Review – ‘Rogue Bras to Bogarts: April Fool’s Day in the Media’

Blog post cover image citation: ‘Spaghetti Harvest Hoax’, BBC, 1957. Public Domain Mark 1.0 (creative and commercial usage, modification and distribution permitted). https://archive.org/details/SpaghettiHarvest. Accessed 7th April, 2019.