By Vanessa Tan, Editorial Assistant with Gale Asia

In 2019, Singapore will commemorate her bicentenary since the landing of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (1781–1826) on the island on 28 January 1819. Raffles’ name now stretches beyond the widely known narrative of the nation-state’s genesis. Today, the name carries pomp and prestige—Raffles City and Raffles Hotel are both prominent landmarks situated in the richest areas of Singapore, while Raffles Institution remains the highest-ranked secondary educational institution in the country, having produced many of the country’s top-performing scholars and politicians.

However, the story of Singapore’s formative years is less of a one-man show. In fact, the founding of the modern nation was based upon a (rather troubled) partnership. If Raffles was the one who dreamt up the blueprint, there was another who built the country’s foundations and set its mechanism in place before it burgeoned into a bustling port—his name was William Farquhar (1774–1839).

Major William Farquhar accompanied Raffles on his expedition that led to the latter’s discovery of Singapore. During the early nineteenth century, the increasing presence of the Dutch on the Malayan Archipelago had become alarming to the British. Raffles hence sought to find a replacement for the British trading port in Melaka, heading south of the Malayan peninsula to the Johor territory.

As explained in Gale’s Encyclopedia of World Biography, the journey eventually landed them on a lowly-populated island which was viewed as an opportune location for trade and business. Under the rule of the Johor Sultanate, the Singapore Island was then facing a controversy surrounding the succession between two brothers in line to the throne. Contrary to the Dutch who had viewed the younger brother as the Sultan of Johor, Raffles bypassed complications and declared the older brother, Sultan Hussein Mohamad Shah, as the sultan of Johor. He then invited him alongside de-facto chief Temenggong Abdul Rahman to the signing of a landmark treaty on 6 February 1819. The 1819 Singapore Treaty stipulated the setting up of a port on the island of Singapore in exchange for an annual payment of $5,000 and $3,000 to both the Sultan and Temenggong respectively.

Shortly after that, Raffles left Singapore in 1819 and handed the command of the settlement over to Farquhar. Farquhar hence became the first official governor of the island. While Singapore was not yet fully under British administration, Farquhar helped set up an administration in Singapore alongside the Sultan and Temenggong; they had “made joint decisions on customs and revenue farms, and conducted judicial trials.”

Farquhar spoke Malay and married a native Eurasian woman, Antoinette Clemaine, with whom he had six children. He was heavily involved in domestic affairs, from which he gained popularity amongst the locals. Not only did Farquhar rule in political, diplomatic and administrative capacity, he “also took on military command of the colony,” protecting the settlement against the threat of Dutch power and their aggressions against the island.

Raffles returned to Singapore in 1822. From October 1822 to June 1823, he spent his time strengthening the British control over the settlement. During this period, however, Raffles and Farquhar had “several points of disagreement on slavery, gambling, and Raffles’ ideas for a new land-reserve system.” In spite of Farquhar’s successful leadership of the nascent colony, Raffles was unable to accept his “toleration – among the native though not the European population – of the opium trade and of slavery.” Raffles ruled out Farquhar for reasons regarding his leadership style and later wrote to the British governor-general in Calcutta to report the dispute. The conflict between the two resulted in the dismissal of Farquhar from his post.

Despite Farquhar’s departure from his post, there is no denying that he had left a legacy worth a publicity as great as Raffles’. After all, Farquhar’s works materialized the visions that Stamford Raffles carried, despite their disagreements, and he was much involved in the domestic affairs of the country. It was during his tenure that Singapore saw a surge in immigration; the population of Singapore reached 6,000 in 1821 and 12,000 by 1823. During these years, Singapore overtook Melaka in its dominance of the region’s trade.

![The Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British India and its Dependencies (London, England), [Thursday], February 1, 1821, Vol. XI, Issue 62, p.199. From 19th Century UK Periodicals.](http://blog.gale.cengage.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/image-2-1.jpg)

Raffles was a true humanist who earned his title through a genuine enthusiasm for his philosophies. This manifested in his career when he greatly endorsed education in the Southeast Asian colonies, and fiercely opposed feudalism, slavery and cannibalism, seeking to outlaw these practices in both Java and Singapore.

We could thus say both men nurtured different aspects of Singapore in its beginnings by building upon each other’s plans and measures. Farquhar had raised Singapore’s economy and free trade, boosted its immigration and set up its administrative structures, while Raffles introduced education, land laws and official jurisdiction. Their leadership shouldered modern Singapore through the rough waters of its starting years, and it’s certainly a history worth rethinking in the nation’s changing political climate and successes in the modern era.

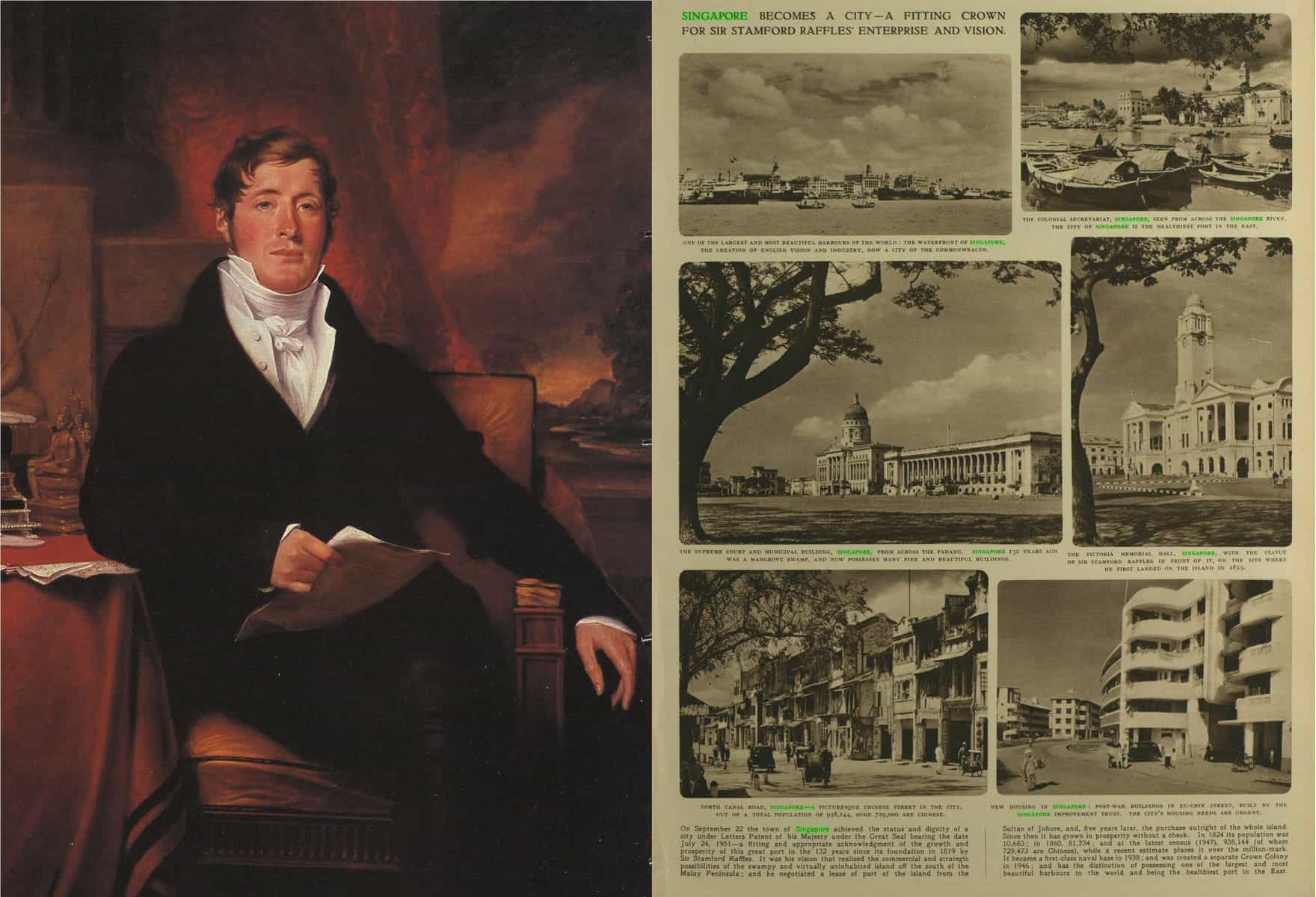

Blog post cover image citation:

Left Geary, Dorothy. “Founding Singapore Capped an Empire Builder’s Great Dream.” Smithsonian, Apr. 1982, p. 131+. Smithsonian Collections Online, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/8rrLj1. ‘G.F. Joseph painted this portrait in 1817, the year Thomas Stamford Raffles was knighted at age 35.’

Right “Singapore Becomes a City—A Fitting Crown for Sir Stamford Raffles’ Enterprise and Vision.” Canadian Royal Tour (Special Number). Illustrated London News, 29 Sept. 1951, p. 483. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/8rurg5