│By Lyndsey England, Gale Ambassador at Durham University│

On the 18th of November 2017, the people of Zimbabwe took to the streets of Harare. Men, women and children walked alongside armed military vehicles, shaking hands with soldiers and standing in solidarity with strangers. In a mass demonstration, members of the public marched united through the capital, calling for the resignation of President Robert Gabriel Mugabe. The march was treated as a ground-breaking moment in Zimbabwean history; an unprecedented declaration of the public’s antipathy towards Mr. Mugabe, the war hero who had ruled since the country’s independence in 1980.

The march took place in the midst of much general political uncertainty. Days before, the military had been stationed in the central business district of Harare, and by the end of the week, the president had been confined to his home by General Chiwenga’s armed forces.

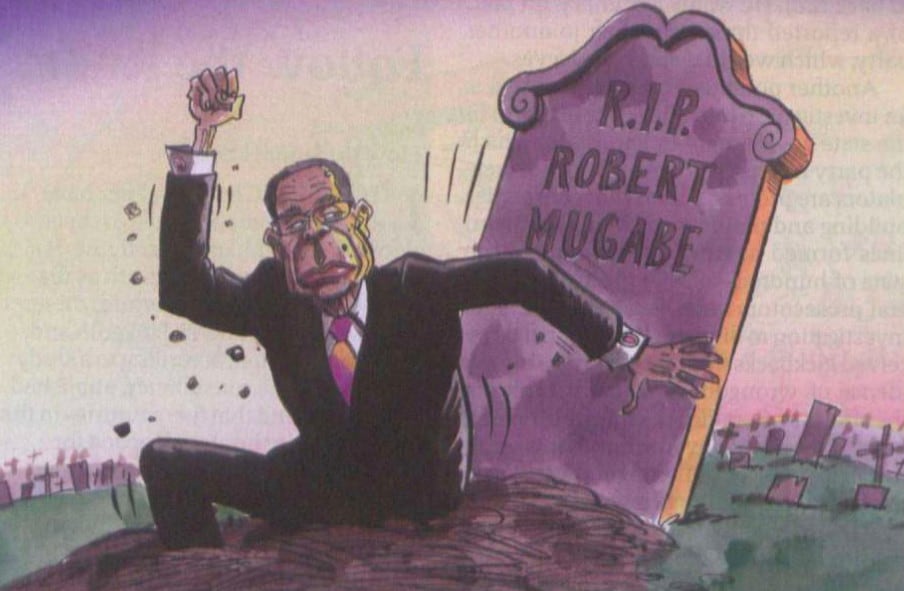

These events were signs of incomprehensible change for many. Gale’s archives illustrate just how unfathomable the idea of Mugabe’s resignation was for Zimbabweans. For decades, the President had rejected claims that he was getting too old for office, clinging on to his title as the world’s oldest ruler. At eighty-six, the president was frequently falling asleep in meetings. In 2015, the year Mugabe was celebrating his ninety-first birthday, his wife was assuring the public that he would not be stepping down in the near future.

Nevertheless, by the 22nd of November, just five days after the march, the aging autocrat had announced his resignation and Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa assumed the presidency. It seemed as though the will of the people had prevailed and Zimbabwe was entering a new era of democracy. The smiles were captured by foreign journalists and broadcast across the globe. In London, the headline of the Metro captured the feeling of euphoria in Zimbabwe: “Hip, Hip, Harare!”

However, looking beyond the overwhelming relief of Mugabe’s resignation, to what extent can Mnangagwa’s political history be comfortably disregarded?

Who is ‘The Crocodile’?

Rising dexterously through the ranks of Mugabe’s ZANU-PF party since 1980, Mnangagwa earned the title of ‘The Crocodile’. Though his assumption of power seemed to suddenly take place over the short space of two weeks, Mnangagwa had been a key member of Mugabe’s inner circle for decades, and many of his actions can certainly be viewed as coldblooded. Most strikingly, it is difficult to ignore the fact that, as head of state security services, Mnangagwa was instrumental in carrying out the gukurahundi massacres of the 1980s. Dubbed as Mugabe’s “right-hand man” by the Independent in 2003, his role in the killing of the Ndebele people is made alarmingly clear.

Moreover, despite popular belief that the military takeover in November constituted a shift towards democratic change, closer analysis suggests that Mr. Mnangagwa’s presidency instead marked a continuation of the wider “Zanu power politics” that had been shaping the country’s government for decades. Since the early 2000s, Mnangagwa had been viewed as a key contender in the presidential succession, and as recently as 2010, an article in The Times noted that the prospect of Mnangagwa assuming the presidency was viewed with apprehension.

Of course, Mr. Mnangagwa’s pragmatic skills and political experience could be favourable to the country’s future. His awareness of the inner workings of the ZANU-PF party and his public persona as a harbinger of peace and democracy can stand him in good stead in terms of bolstering relations between Zimbabwe and the West.

Based on his re-election in 2018, it could be assumed that the 73-year-old has managed to garner the affection of his people despite his soiled past. Speaking to Sky News in August 2018, Mnangagwa said, with deliberate slowness: “I am as soft as wool”. However, in the midst of these ‘harmonised elections’, MDC-Alliance protestors challenging the validity of results in the centre of Harare were confronted with open fire. Unarmed civilians were shot in the back, with several people killed as they fled from the army they had embraced less than twelve months before.

It would not be unfitting to have described this incident with the same headline as one the Daily Telegraph used to describe Zimbabwe in 2000 – ‘Violence Revives Memories of Massacre Years’. Indeed, the article made a statement which could ring true for Zimbabweans today:

Although the leadership of the party may have changed, the mechanics of ZANU appear to remain the same. Mr. Mnangagwa may well be covered in wool, but he could have the teeth of a crocodile hidden away beneath his sheep’s clothing.

Only time will tell whether Zimbabwe has truly entered a new era of peaceful governance.

Blog post cover image citation: “Stealing the vim from Zim.” Economist, 10 Aug. 2013, p. 40+. The Economist Historical Archive, 1843-2014, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/8VCfq5