By Carolyn Beckford, Gale Product Trainer

Today is International Day of the World’s Indigenous People. This was first put forward by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1994, and came as result of a commission designed to promote and protect Human Rights. Now, on 9th August, the world works to remember, recognise and respect the rights of indigenous populations and celebrate their achievements and contributions.

There are approximately 370 million indigenous people in the world. Belonging to approximately 5,000 different groups living in almost 100 countries, they’re found in every region of the world, though the majority are in Asia. Also referred to as first peoples, native peoples or aboriginal people, indigenous populations are those who have a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories. Indigenous people typically form the non-dominant sectors of their society. They often consider themselves distinct from other sectors of society currently living in their territory. Despite colonialism, industrialism or modern innovations, indigenous people are often determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ethnic identity based on their continued existence, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems.

Historical descriptions of indigenous people: the evolving use of terms

The term ‘indigenous’ is a twentieth-century creation. Throughout history, there were several other less politically correct ways to describe and refer to indigenous people. If you search in Gale Primary Sources you’ll find earlier uses of the term ‘indigenous’, but in reference to plants or animal species rather than people. For example, an article entitled Aboriginal Baby printed in 1896, now included in Gale’s British Library Newspapers collection, was referring to the antics and exploits of a baby koala, not native people!

A rather disparaging way to describe indigenous people, particularly used by settlers in North America, was ‘savages’. In George Turner’s Traits of Indian Character, they were routinely described in this way, although their racial and ethnic background was known.

‘Native’ was probably one of the most common, more apt, terms used to describe indigenous people. One of the first references found in Gale Primary Source is in a monograph dated 1847 in Sabin Americana entitled, Adventures in Mexico in which the author describes the native people as beautiful.

When European settlers first encountered indigenous people, they often sought to change their beliefs and way of life; the goal was to convert them to European customs. These actions began gradually wiping out indigenous culture, belief systems, languages and identity. The monograph below from Sabin Americana highlights the intent of settlers to ‘propagate Christian Knowledge’ to the indigenous peoples of the Americas, while the American Aboriginal Portfolio highlights efforts to ‘Christianize’ them.

Indigenous culture was also under threat because it was different to what the invaders knew. Several hundred indigenous groups lived in Australia prior to British colonisation. They lived in clans or extended family groups defined by various kinships and rules that governed social interaction, family responsibilities and marriage. This family culture and kinship amongst the aboriginal people was described by the invaders as ‘curious’.

Early studies of indigenous peoples

Although there were concerted efforts in many areas to wipe out indigenous cultures, there was also a fascination amongst many Europeans about these traditions and ways of life. This curiosity led some settlers to study indigenous cultures, with varying levels of sensitivity, and individuals also travelled from Europe to research native peoples.

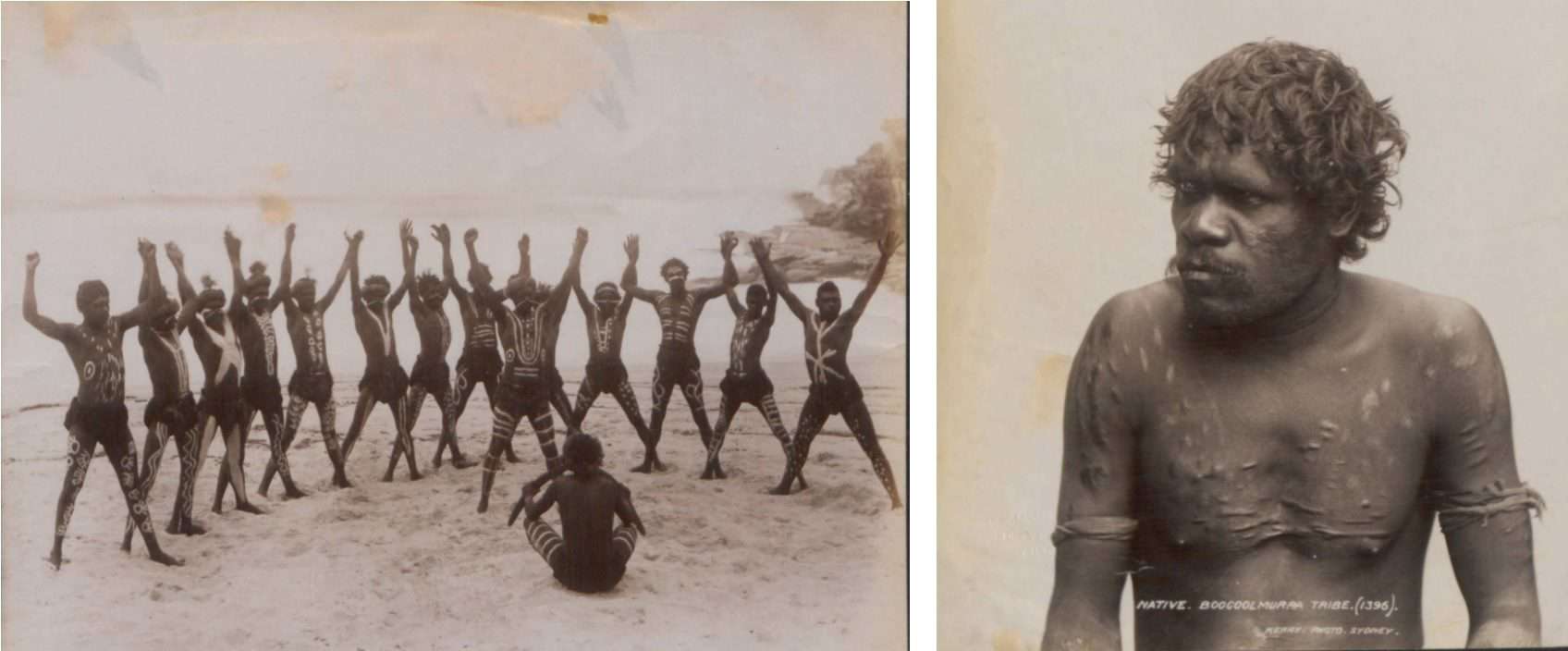

Early images of indigenous peoples can be found in Nineteenth Century Collections Online. The examples below show a variety indigenous people from around the world.

Continuing discrimination today

Why is a special day needed to celebrate the indigenous peoples of the world, you may think – surely Human Rights laws and statutes protect them?

They make up less than 5 per cent of the world’s population, but account for 15 per cent of the poorest. Indigenous populations all around the world are continuously ostracised, whether by happenstance or self-imposed separation, because they don’t subscribe to the dominant culture in their territory. Due to their distinct culture, dress and belief system, indigenous people may not blend into the dominant culture. Children of indigenous peoples may not attend state schools; adults may not subscribe to the legal system or rules of the dominant culture; they may not be employed in traditional environments; and they won’t always access hospitals or government support because of their beliefs. Even groups sometimes seen as stable or privileged, such as certain Native American nations or the Maori, continue to have considerably lower life expectancy and higher rates of alcoholism and poverty than non-indigenous citizens of their countries.

The indigenous people in Canada are some of the most marginalised indigenous populations in economically developed countries, experiencing higher unemployment, suicide, mental health problems and incarceration rates. Coupled with lower levels of education, health care access and income than the rest of the population, the indigenous people in Canada are under severe threat of extinction.

Indeed, in The Manifesto of National Indian Movement (below), the Canadian government is accused of genocide towards the indigenous population because of political, economic, religious and social oppression.

Indigenous women in Canada still feel they are discriminated against in housing, employment and health care.

Indigenous Peoples: North America, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6mHrXX

Australia also has severe imbalances between the treatment of indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. Indigenous groups were not previously included in the national census, so their exact numbers are not known. They’re thought to make up approximately 4% of the total population, though – yet they make up approximately 28% of the prison population. The health and economic difficulties facing the indigenous population are substantial, with higher rates of health problems, particularly mental health, higher unemployment rates and poverty.

For almost 100 years, Australia’s indigenous children under 12 years of age who had any white ancestry were systematically and legally removed from their families by Australian government agencies and church missions. The intent was for them to assimilate with the white community to which the government felt they rightfully belonged. They are widely known today as the ‘stolen generation’.

Indigenous Australians feel it was attempted genocide by the government and the population still deals with the effects of it today. They are still seeking a national apology from the government and restitution for the policy, which was widely implemented across the country.

Gray, Geoffrey M P, and Matthew White, Chairman. “Lonely and lost in Australia.” Independent, 23 June 1997, p. 14. The Independent Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6mKNX7

There is still distrust between the Australian government and the indigenous population who are calling for legal restrictions to ensure their children are not adopted by white Australians. They feel it would be detrimental for the culture and future of the indigenous people.

Governments tend to support each other for the benefit of trade and territorial reasons, amongst others. Countries without indigenous populations (in the sense discussed in this post) sometimes unwittingly disadvantage indigenous ways of life in favour of strengthening partnerships with former colonies and in support of the dominant culture. In the below article, for example, Britain voted to block an attempt to have the rights of indigenous populations like Native Americans, Maori and Aboriginals protected under international law.

Legal protection and cultural celebration

Indigenous peoples have sought recognition of their unique identities, way of life, traditional lands, territories and natural resources for centuries. However, throughout history, their rights have been routinely violated, usually in favour of the dominant culture.

The international community now recognises that special measures are required to protect their rights and maintain their distinct cultures and way of life. ‘Indigenous’ is now a legal category in national and international legislation, identifying those of a culturally distinct group affected by colonisation. Despite efforts to protect indigenous people, it is still very necessary to highlight the plight of the world’s indigenous people in an effort to ensure their survival. It is also important to protect their rights as human beings and celebrate their diversity. The International Indigenous Peoples Day seeks to highlight the distinct and unique culture of indigenous populations, and shine a spotlight on their history. Commemorative activities around the world include educational forums, cultural examples of dances, dress and art.

How much do you know about indigenous populations living in your region? As today is 9th August, International Day of the World’s Indigenous People, challenge yourself to learn more about their unique culture and heritage!