By Carolyn Beckford, Gale Product Trainer

Every July 4th I send holiday greetings to my friends and family in the USA and they always say, “same to you”. I remind them that July 4th isn’t a holiday in the UK. As an educator, I relish the opportunity to highlight and explain why American Independence is not celebrated with euphoria in the UK as it is in America.

We can see from the map below, found in Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers, that the territory under British rule was once immense and spanned the globe, leading to the well-known quote that Britain had “the empire on which the sun never sets.” The British colonisation of the Americas began in 1607 and before long, colonies had been established throughout the Americas.

Known as British America until 1776, when the Thirteen Colonies declared their independence and formed the United States of America, the colonial citizens in British America were relatively content under British rule – but only if they had authority over their own destiny, something they still hold dear.

The Stamp Act: 1765

Tensions increased when the British government tried to gain increased control over the colonies, and introduced measures to collect a series of revenues. In an effort to offset their own war expenses, the Halifax Letters set out the right of the English Parliament to tax the colonies, hence the creation of the Stamp Act of 1765. British America took exception to taxation without direct representation in Parliament, and the letter below from the Cygnet Commander to Secretary Conway found in State Papers Online gives an account of the riots and tumultuous behavior that resulted from the introduction of the Stamp Act.

Riotous behavior continued for four days, during which three effigies of customs collectors were hung on gallows then later cut down and burned in a bonfire. Other custom officials had their houses set on fire or were attacked on the street and had to flee.

In the article above published in the National Advocate all Americans were encouraged to start a revolution if necessary. To them, the idea of taxation without representation meant they “would maintain under the British dominion as slaves, not as fellow citizens,” of which they were fiercely opposed.

In a Summary View of the Rights of British America (below), which, according to a list of publications in Sabin Americana, sold for $2.00, Thomas Jefferson highlighted why British America needed to be free from its colonial master. He suggests that prior to moving to British America, they were free inhabitants; a right nature gives to all men, and that moving to the colonies in no way changed, neither by choice nor chance, that to which he felt they were previously entitled under laws and regulations.

The summary pamphlet could be purchased, and the piece was also printed in full in newspapers.

Resistance to the Stamp Act was so vociferous, the measure became increasingly unenforceable. Eventually Parliament revoked the Stamp Act, although it insisted Britain still had complete legislative authority over the colonies. While the repeal of the act was welcomed, colonial defiance and mutual distrust had been created.

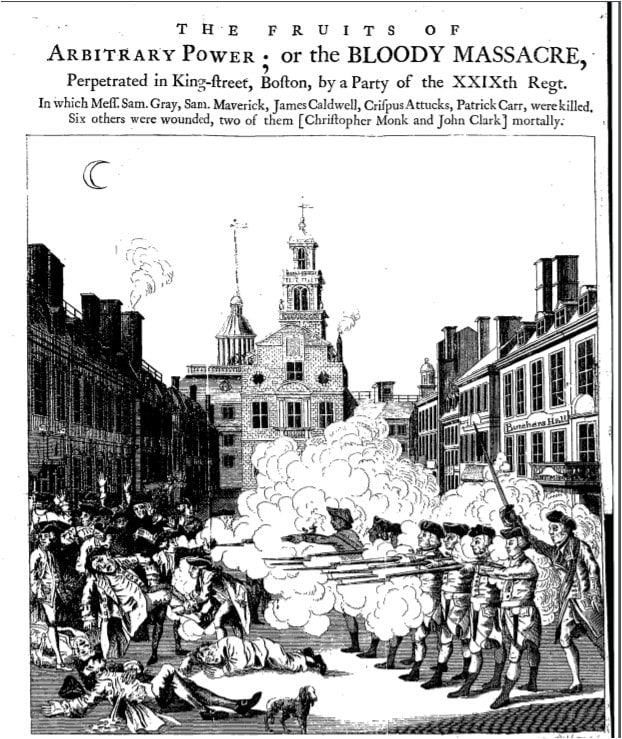

The Boston Massacre: 1770

A series of incidents took place after the repeal of the Stamp Act that increasingly emphasised the differences between the colonies and Britain. This includes the taxation of imports, boycott of British goods in the colonies, and the Boston massacre, also referred to as “the bloody massacre”. The latter is considered one of the most important events that turned colonial sentiment against King George III and British Parliamentary authority. British troops were stationed in Boston to protect and support Crown-appointed colonial officials, and to enforce parliamentary legislation. In March 1770, with heightened tension between the population and the soldiers, a mob formed around a British sentry, who was subjected to verbal abuse and harassment. Eight additional soldiers came to his aid, and they were also subjected to verbal threats and reportedly hit by stones. The soldiers then fired into the crowd, without orders, instantly killing three people and wounding others. Two more people died later of their wounds.

In The History of the Boston Massacre, found in Sabin Americana, John Adams writes that “on that night the formation of American Independence was laid” because of the nature of the attack and the deaths incurred; it was seen as a most abominable and unforgivable act. He goes on to say the nature and importance of this event led to a more meaningful and long-lasting feeling of indignation against the King, Parliament and the ruling powers of Britain. As a result, the nation could only hope and trust in an independent American government.

The Tea Act: 1773

The ongoing dispute over the authority of Parliament in British America intersected with the financial problems of the British East India Company, and the desire for tea in the colonies. The below document from State Papers Online details the vast amount of tea being consumed in the colonies. Parliament saw an opportunity to increase taxation revenue via this consumption.

The taste for tea had developed in Britain in the seventeenth century when it was imported from China. The British Parliament gave the East India Company a monopoly on the importation of tea. When it also became popular in the British colonies, Parliament sought to eliminate foreign competition by passing the Tea Act that required the colonies to import their tea only from Great Britain. (The East India Company was required to sell its tea wholesale in England; British firms bought this tea and exported it to the colonies, where they resold it to merchants in Boston.)

As a result, British Americans smuggled tea at much cheaper prices from elsewhere. To support the East India Company, Parliament levied new taxes on tea. The Boston Tea Party was formed as a political protest group. They boarded the ships importing tea, threw chests of tea into the Boston Harbour and destroyed an entire shipment of tea sent by the East India Company. The colonists objected to the Tea Act because they believed it violated their rights as Englishmen. The Act strengthened views that taxation should only be conducted by their own elected representatives – not by a British parliament in which they were not represented. In addition, there was resentment that the well-connected East India Company had been granted competitive advantages over colonial tea importers. The below article from the American Independence, found in Gale’s archive Sabin Americana, argues they were justified in destroying the tea in Boston Harbour.

Though the Tea Act was repealed and formally removed from the books, it served to stoke growing colonial fears that Britain was attempting to limit freedom throughout the colonies. A break from England was becoming a distinct possibility.

Conflicts, protests and boycotts continued to be a feature in British America. Britain closed the Boston Harbour and passed a series of measures against the colony. In response, a shadow government was set up to take control from the Crown; twelve of the Thirteen Colonies formed The Continental Congress to discuss their own issues and effectively started to manage themselves.

The Continental Congress and Continental Association

The official request to hold a congress (below), found in Eighteenth Century Collections Online, requested to “lay their grievances before the throne”. The Congress outlined the collection of taxes as an issue, and the behavior of British officers, complaining that the “usual officers had departed and new, expensive and oppressive officers had been multiplied”.

By the spring of 1776 a series of events and hostilities had transformed the political landscape in British America into full rebellion. With the events in Boston and the closing of the Harbour still very much remembered, there were several battles, a gunpowder plot and hostilities in several colonies. The documents below in State Papers Online indicate the dilemma presented to King George. The first is a cabinet meeting relating to measures for the suppression of the rebellion in America. The second document, a letter to the King, expresses “deep concern that the subjects in America have adopted principles subversive of all legal governments” and was now in a state of serious hostility. With the colonies openly attacking monarchical government, King George declared that British America was in open rebellion.

http://go.galegroup.com/mss/i.do?id=GALE|MC4589482245&v=2.1&u=webdemo&it=r&p=SPOL&sw=w&viewtype=Manuscript

Address of the Ministers and Elders of the provincial synod of Angus and Mearns to the King against the rebellion in America. Signed James Adamson, Moderator; Dundee, 25 Oct.1775. Document Ref.: SP 46/151 f.348 Folio Numbers: ff. 348 Date: 25 Oct 1775 Gale Document Number: MC4637780150 State Papers Online

The Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress in 1776, announcing that the Thirteen American Colonies who had been at war with Great Britain, would regard themselves as thirteen independent sovereign states, no longer under British rule.

The Declaration, along with full details of all the signers, were formally submitted to the King.

The Declaration set out and justified the reasons for breaking from Great Britain by highlighting colonial grievances against King George III, and by asserting what they understood to be their natural and legal rights. One of the key lines in the document that has been adopted as a statement on human rights, is the second sentence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”. This has been called “one of the best-known sentences in the English language” containing some of the most significant and consequential words in American history. That sentence represents, even today, a moral standard to which the United States continues to strive.

So, the history leading to the independence of the United States of America is fraught with violence, rebellion and a struggle for self-rule. It is unlikely that it will ever be fondly celebrated in the United Kingdom. Each year though, the history takes a back seat to the fireworks and hot dogs that are an integral part of the celebration in the US. Undoubtedly I will get Happy 4th of July greetings this week, and I’ll be ready to yet again highlight some of the history of how Great Britain lost British America, leading to the creation of the United States of America.