By Becky Wright, Gale Content Researcher

Gale’s digital collections include a wealth of newspapers, journals and periodicals. From The Times Digital Archive to the newspapers in the 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection, and from the International Herald Tribune to Missionary, Sinology and Literary Periodicals published in China, researchers have access to a vast array of English-language journalism, spanning centuries and continents. With the inclusion of early newspapers and periodicals in the resource Early Arabic Printed Books from the British Library, this archive offers researchers the opportunity to trace the development of Arabic print journalism as well. While the digital collection was being created, I was lucky enough to see some of the originals at the British Library. I was struck by the diversity of the journals, both in subject matter and appearance, but such variety is not so surprising considering the titles span more than thirty years (1861 to 1899) and were produced in several different countries.

Modern journalism in the Arabic-speaking world can be traced back to “European colonization of much of the region, beginning in 1798. The earliest newspapers were published in languages not indigenous to the region, and for the consumption of ruling forces or foreign diplomats”[1]. This year, 1798, marked the French invasion of Egypt under Napoleon who bought with him two printing presses with characters in Arabic, French, Latin and Greek. It was to be around 24 years, however, before the first periodical appeared in Arabic circa 1822. It was printed in Bulaq, Egypt, in both Arabic and Italian at the Ecole Polytechnique. From the start, the scope of Arabic journalism was far broader than simply the dissemination of news. It was ‘strongly influenced by writers, poets, and intellectuals’ and ‘served as a platform for essays on society, culture, religion, and politics’.[2]

In 1860, the first issue of what has been called ‘the greatest Arabic newspaper of the nineteenth century’[3], was published. al-Jawāʼib was published weekly in Constantinople by Ahmad Faris al Shidyaq. Born a Maronite Christian in 1804, he converted to Protestantism in 1826 and amongst other literary endeavours, produced an Arabic translation of the Bible. After extensive travel, he lived in Tunisia and while there converted to Islam. His move to Istanbul (Constantinople) in 1860 preceded the publication of al-Jawāʼib. The newspaper was ‘a mouthpiece for Ottomanism which soon became a leading forum for the discussion of the political and cultural issues of the time and can be considered a pioneer of modern Arabic journalism’.[4]

“طبيب العائلة” [“Tabīb al-ʿāʾilat”]. طبيب العائلة ومرشد اللبيب عند غيبة الطبيب [Ṭabīb al-ʿāʾilah wa-murshid al-labīb ʻinda ghaybat al-ṭabīb], 15 Apr. 1896. Early Arabic Printed Books from the British Library, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6fZsN3. Accessed 18 June 2018.

Habib Anthony Salmoné published what was described by A. G. Ellis (who catalogued the Arabic books now at the British Library in his Catalogue of Arabic books in the British Museum) as ‘a monthly magazine of politics, literature, and science’. Salmoné chose at first to publish two editions simultaneously; one in Arabic called Ḍiyāʾ al-khāfiqayn, and one in English called The Eastern and Western Review. According to Ellis, however, the Arabic edition appeared to stop after the second number. The images below show the front pages of the two first editions.

‘…it has been proposed to start a literary and scientific periodical for circulation in the East, to be edited in Arabic, with occasional articles in Hindustani, Persian and Turkish. It will contain a summary of passing events, and articles on scientific, literary, and artistic subjects, with notices of important discoveries and inventions. It will be rendered additionally attractive by the use of high-class illustrations, and will be the first illustrated literary Magazine in all of Asia and Africa.’[9]

By the second issue articles were being published in English and Arabic side by side as shown here in a curious article on possible futuristic uses for the telephone!

“A Remarkable Application of the Telephone.” النحلة [al-Naḥlah], 1 July 1877, p. ٢٩-29. Early Arabic Printed Books from the British Library, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6fax53. Accessed 18 June 2018.

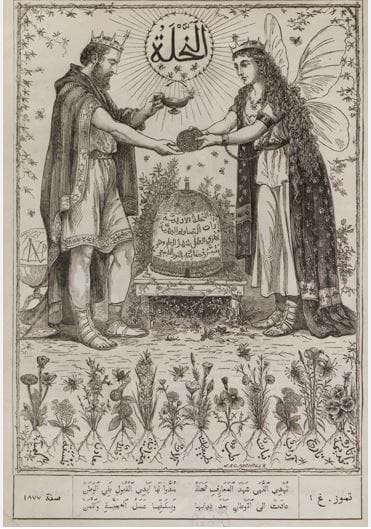

Blog post cover image citation: “النحلة” [“The Bee”]. النحلة [al-Naḥlah], 1 July 1877. Early Arabic Printed Books from the British Library, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/6fasw0. Accessed 18 June 2018.

[1] Simons, Char. “Journalism: The Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia.” The Oxford Encyclopedia of The Modern World, edited by Peter N. Stearns, vol. 4, Oxford University Press, 2008, pp. 332-334. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX1549101033/GVRL?u=gale&sid=GVRL&xid=accf4aae. Accessed 18 June 2018.

[2] Koren, Haim. “The Middle East Media: An Introduction.” The Middle East: A Guide to Politics, Economics, Society, and Culture, edited by Barry Rubin, vol. 1, M.E. Sharpe, 2012, pp. 217-231. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3222300037/GVRL?u=gale&sid=GVRL&xid=0e25d614. Accessed 19 June 2018.

[3] Lewis, B., et al. “D̲j̲arīda.” The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New ed., vol. 2, E. J. Brill, 1991, pp. 464-479. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX2686302274/GVRL?u=gale&sid=GVRL&xid=b6666275. Accessed 19 June 2018.

[4] Denoeux, Guilain P. “Shidyaq, Ahmad Faris al- [1804–1887].” Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa, edited by Philip Mattar, 2nd ed., vol. 4, Macmillan Reference USA, 2004, p. 2051. Gale Virtual Reference Library, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3424602484/GVRL?u=webdemo&sid=GVRL&xid=d492106c. Accessed 1 Dec. 2017.

[5] Snir, Reuven. “Press, Arab-Jewish.” Encyclopedia of Modern Jewish Culture, edited by Glenda Abramson, Routledge, 2005, pp. 697-704. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX6143800791/GVRL?u=gale&sid=GVRL&xid=833b2eb0. Accessed 18 June 2018.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid

[8] Lewis, B., et al. “D̲j̲arīda.” The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New ed., vol. 2, E. J. Brill, 1991, pp. 464-479. Gale Virtual Reference Library, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX2686302274/GVRL?u=gale&sid=GVRL&xid=b6666275. Accessed 19 June 2018.