By Alice Clarke

“Elbows off the table” is a phrase familiar to most ears, an order we were told as a child and to which the only response was obedience and, for me, an internal eye-roll of frustration.

For this is an etiquette that transcends generations, centuries and traditions, and yet is something that no one appears to explain why it exists. The only answer I could ever muster from my parents and grandparents is the ever-evasive “it’s rude to have your elbows on the table”, and that was meant to be enough to pacify us.

But why is it rude? Elbows aren’t unhygienic, unsafe or indeed disrespectful in any other setting than touching the wood of the dinner table.

And yet, to this day, I still sit with my elbows off the table – seemingly engrained into my very subconscious, this rule still governs the comfort of my eating despite the fact I moved away from home to university over two years ago.

To gain some sort of understanding of what this rule originally meant, a quick search of Gale Primary Sources allowed me to trace the notion of “elbows off the table” through history across multiple primary sources, allowing me to form my own theory of this particular western etiquette.

The earliest mention I could find was in a book of etiquette, A Gentlewoman’s Companion, published in 1673 (below). The first thing I noticed was the emphasis these instructions placed on having your elbows off the table as it appeared in the very first sentence of a chapter dedicated to ‘Behaviour at [the] Table’. The instruction given is clear and abrupt with no explanation as to why this is so important, which suggests it was already a pre-established rule in society, perhaps previously a spoken rather than written rule.

Yet the other instructions in this passage could give us an indication of why to ‘lean your elbows on the table’ was so taboo at the time as it sits beside requests such as to keep one’s ‘body strait in the chair’ and not to ‘fix your eyes greedily’ on your food or ‘devour’ your meal. Both of these are presentational forms of etiquette, and the almost animalistic language used (‘ravenous…greedily…devour’) could suggest placing your elbows on the table is of similar barbarity as placing your dinner on the floor and eating on all-fours.

The idea of the elbows-off-the-table rule being connected to a lower social standing was a trend I noticed across several articles spanning the seventeenth to the late nineteenth centuries, but it wasn’t until I came across this article from 1899 that the connection between social hierarchy and the use of elbows was a little more explored:

Here, the reporter tells of a social event in a local paper, intriguingly describing the variety of class in the guests as the upper class being covered up in ‘fur-lined coats and silk hats’ but ‘knocking elbows’ with the lower, ‘seedy’ classes that were ‘very much out at the elbows’.

The description of the lower class being bare at the elbow reminded me of other western idioms such as “elbow grease” or to be “elbow deep” in work, almost as though there is a common connection between one’s elbows, manual labour and the lower class. The contrast of this and the richer guests here covering their elbows with rich fabrics could suggest that to show the elbow is not a thing to do in high society, even by resting them on the table.

A second notable trend was that young women were often the audience of elbows-off-the-table instruction, appearing in multiple etiquette books for young women of society throughout the ages. Below, the text from 1896 is the opening to a subsection of a chapter about the appropriate fashion choices of a young woman, with an entire subsection dedicated to covering the arm to keep one’s dignity.

The description of a woman’s arm being a ‘defect’ often without ‘correctness of form’ that should be hidden from the shoulder to ‘just below the elbow’ by ‘lace and frills’ suggests that to expose this part of the arm is un-lady like and indelicate, again suggesting it should be hidden from view at social occasions but this time to preserve a woman’s delicate appearance.

After the turn of the twentieth century, however, the forcefulness of reinforcing elbows-off-the-table decreased quickly, as discussed below this had utterly changed in a public restaurant in 1944:

This second half of the article describes how ‘nowadays the prejudice [to having your elbows on the table] has died out’, but more than that, it is used as a ‘great aid to conversation’. The writer explains how to ‘lean forward with elbows on the table’ can give ‘animation’ and passion to someone’s conversation, and so has changed into a more positive social position than only fifty years before.

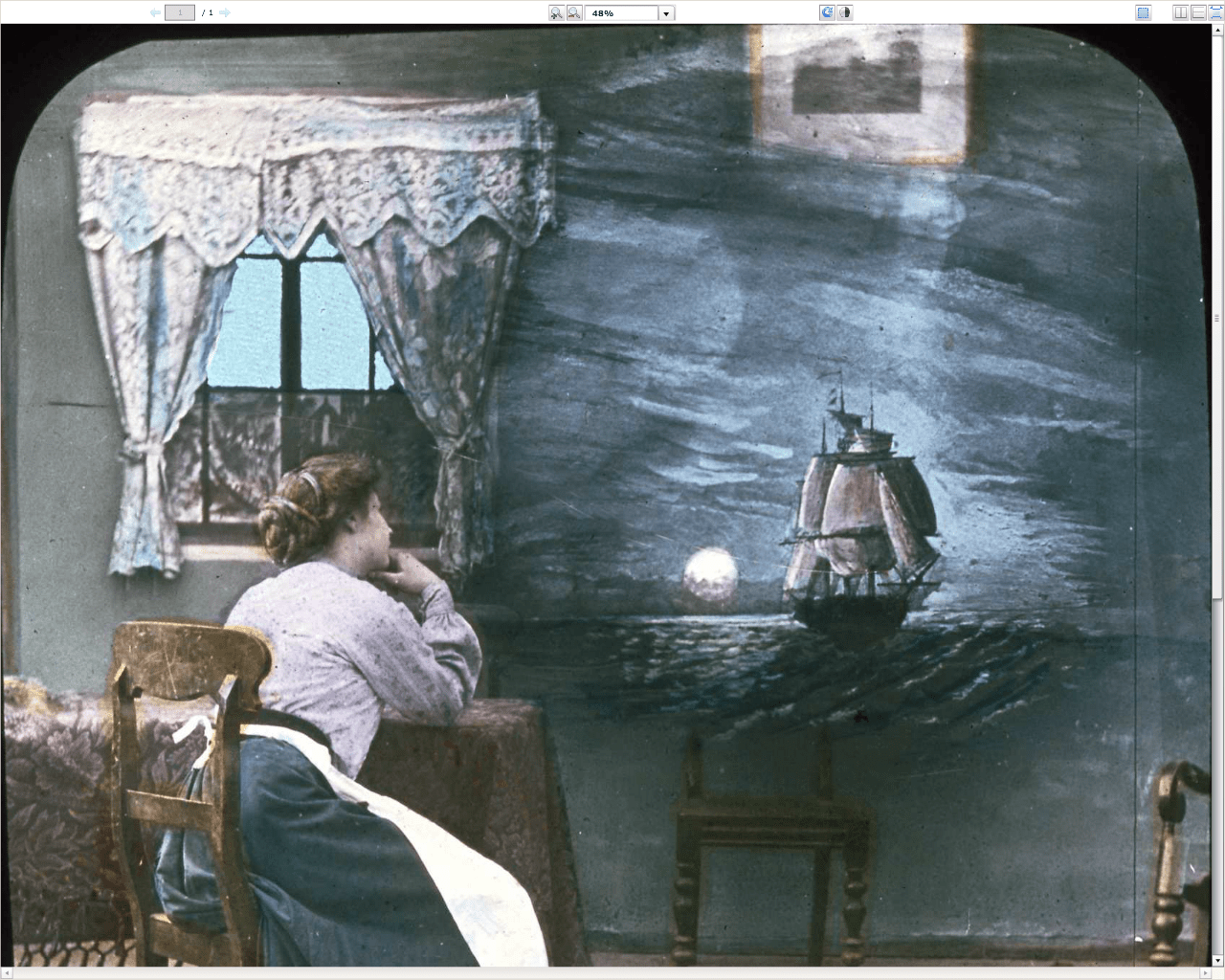

The article also reflects on how the position was traditionally a post for the ‘love-lorn and forsaken maiden’, again making an interesting link between elbows and gender, just like the painting below from 1895.

Certainly the rigidity of elbows-off-the-table has decreased in the last century, to now be viewed as a little old-fashioned and ridiculous. Yet it still is a widely obeyed command, despite having no practical or even societal implications anymore, only existing today as something said to us by our parents because their parents said it to them. For in the modern age, it’s less a command and more an empty echo across the generations trying to tell us that this is how the world ends, not with a bang but with an elbow on the table.