This is the second of two posts exploring how lively debate and strong clashes of opinion have coloured the British press at certain historical moments. My first post looked at the differing opinions printed prior to, and during, WWI. Firstly, this showed that opinion was split on the likelihood of war in Europe, and then, once Europe had indeed plunged into a long and bitter war, news commentators clashed on the leadership of the British army – a debate which spiralled on in the succeeding decades. (Click here to read the first post.) I’ll now be turning to the broad landscape of opinions and commentary which permeated the British press in response to the rise of fascism. Interestingly, as well as some of the most well-known arguments, this post brings to the fore views which have now been side-lined, discredited or simply eclipsed by modern interpretations.

Before diving into the impassioned articles and heated exchanges, it’s interesting to provide a quick outline of the political positions held by the newspapers in the Gale Primary Sources programme – though of course, these have sometimes evolved over time.

With the apparent failure of capitalism following the 1929 Wall Street Crash and resultant Great Depression, democracy itself was seen to be in crisis, and people searched for an alternative. Notable thinkers of the day used the pages of The Listener as an arena to deliberate and express their convictions about the nature of governance, which you can now read in The Listener Historical Archive. George Bernard Shaw, Beatrice Webb and Leonard Woolf were particularly vocal in their views on the nature of the state and society. In 1931, Woolf wrote a thoughtful analysis in The Listener of the state of democracy in contemporary Europe. He suggested that ‘Democracy, though out of Favour – has steadily Gained Ground’, as well as considering where it came from, who now supported and opposed it and how, paradoxically, these people were often not those who would have been for or against democracy five decades previously. He also outlined what, in his opinion, constituted democracy, and how neither communism nor fascism could fit the requirements.

Intellectual debate about the merits, or lack of them, in alternative political systems were also explored at greater length in books; titles on communism and fascism were regularly reviewed in the Times Literary Supplement.

The Times Literary Supplement 10 Aug. 1933: 531. Times Literary Supplement Historical Archive

Many articles went beyond impartial commentary, clearly arguing for the superiority of one political structure over another. George Bernard Shaw was increasingly supportive of the communist Soviet Union, and was not alone in his views.

As the mouthpiece of the BBC, The Listener aimed for impartiality – and equal representation of conflicting opinions. Following Hitler’s appointment as Chancellor of Germany, they printed a debate entitled ‘Does England need Fascism?’ in which a strident argument for fascism by Sir Oswald Mosley, leader of the British Union of Fascists, was immediately followed by an argument against. Consequently, the publication did give something of a voice to writers who strongly believed fascism was right for Britain, a view rather discredited today. Indeed, it is often forgotten – eclipsed by ubiquitous representations of the Allies fighting an honourable war against fascism in WWII – that some people within Britain had attempted to establish a fascist government.

Other publications would go further still in their support for the ‘new right’. The Daily Mail famously endorsed Mosley’s fascists in 1934, having already secured an exclusive interview with Adolf Hitler in 1933 and written approvingly of Mussolini’s Italy, all of which can be read in The Daily Mail Historical Archive 1896-2004. ‘Fascism,’ the Mail wrote, ‘…stands in every country for the Party of Youth. It represents the efforts of the younger generation to put new life into out-of-date political systems.’

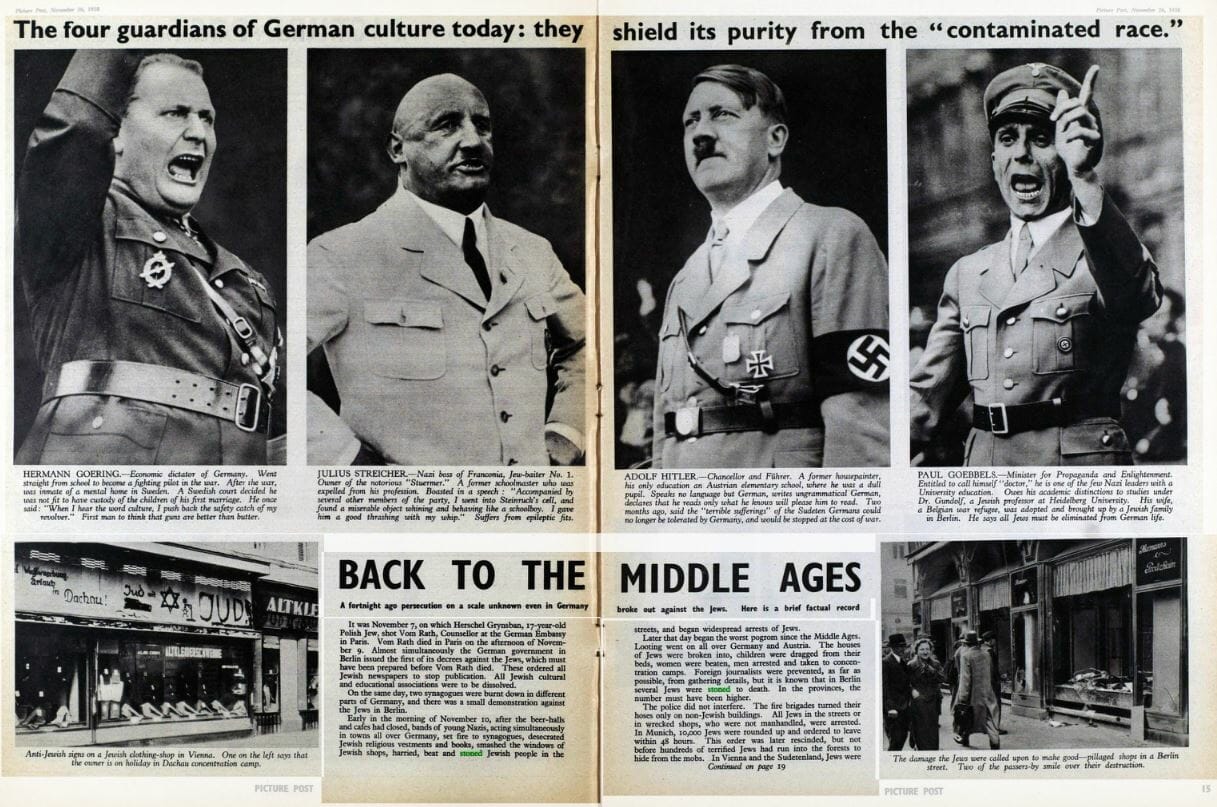

At the opposite end of the scale, the Picture Post was fiercely opposed to fascism from its very first issue. A 1938 article entitled ‘Back to the Middle Ages’ made no secret of what it thought of Nazi Germany at a time when many in the establishment still sought to accommodate Hitler.

Even in newspapers that cleaved to the centre, the war of ideologies can be seen on ‘letters’ pages. An exchange in The Times Digital Archive from 1933, for example, exemplifies different attitudes towards anti-Jewish activity in Nazi Germany. Newspapers can, therefore, not only show researchers what happened in history, but how the opinions and attitudes which in turn induced certain decisions or actions initially developed, helping to explain why events occurred as they did.