Written by Jess Edwards and Daniel Pullin

In case you missed it, last week we posted the first instalment of our extended exploration of the development of the modern British palate. Inspired by the events taking place around the UK for British Food Fortnight, we considered what actually constitutes ‘British Food’. The phrase can, of course, describe food produced in Britain, but it could also mean the food eaten most regularly in the UK, and entrenched in British culture – and many of the meals commonly eaten in Britain today have been introduced from foreign shores. Last week we unearthed historical copies of recipes for, and discussion about, two meals which have become staples in the British diet; curry and pasta. We also rustled up our own versions using the following historical instructions! (Follow this link to see the results of our culinary experiments!)

This week we’re continuing our investigation into the historical background of foods commonly consumed in modern Britain, and this time we’ve chosen to focus on a couple of recipes with clearer British origins. Both have still, however, undoubtedly undergone their own evolution and adaption – even if largely due to the impact of mass production!

It’s not hard to appreciate how deeply rooted the Cornish pasty is in British culture if one takes note of quite how many bakery outlets there are across the country selling their own versions of these meat-stuffed pockets, even if they exhibit a considerable amount of diversity. Perhaps as a result, special European protection was granted in 2011 to regulate what makes a pasty truly ‘Cornish’.[1] Given this, it is perhaps unsurprising that, looking through the Gale archives, we found signs of fierce contestation over the composition of a pasty, which was already perceived as the county’s ‘standing dish’ in 1861.[2]

Take the Cornishman’s 1880 article ‘How to Make, and Enjoy, a Cornish Pasty’.[3] The ‘secret’, according to the paper’s correspondent, lay with the ‘seaming up’ of the pasty, which determined where the ingredients fell once successfully formed.

Much like today’s strictly Cornish interpretation, beef and potatoes were the central ingredients. The aesthetics of the pasty were crucial too. A 1908 piece in the same newspaper lamented an American interpretation of the pasty on a postcard, which was nothing more than a ‘vile caricature’, bearing as much resemblance to a chrysanthemum as a pasty![4] It seems that notions of what made pasties ‘Cornish’ have become progressively more entrenched. With such rigid strictures in place, there was some pressure on our own interpretation of this classically Cornish dish…

When considering desserts, there are few things more quintessentially ‘British’ than the apple pie. Traditionally served with cream or lashings of hot custard (Daniel’s preference!), the apple pie has long been considered the perfect, comforting way to round off a meal. Even 300 years ago (the first reference to the dessert in Gale Primary Sources is in a pamphlet from 1713), it was commended for its ‘outward beauty and inward taste’, with ‘a nice and perfect account of the origin, progress, art, and method, of that incomparable viand’.[5]

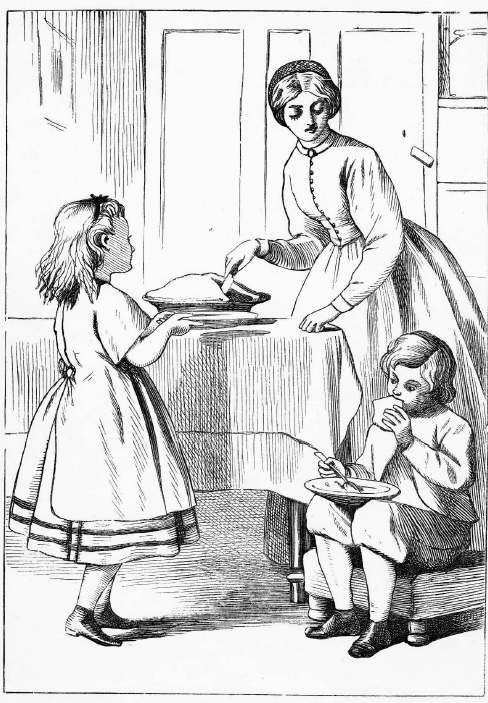

When further exploring Gale’s resources, we were struck by how culturally ingrained the apple pie has become, as it even features in numerous plays, poems and books. The 1829 pantomime ‘A. Apple Pie; or, Harlequin Alphabet’ – based on the nursery story ‘A, apple pie’ – seemed particularly popular, and was reported in more than one contemporary newspaper (source 1; source 2).[6] The dessert features prominently in the title of the story, and the entire rhyme is dedicated to it, telling the tale of 26 children (one for each letter of the alphabet) who are desperate to get their hands on the pie.[7] This suggests that children of the time would have been very familiar with the concept of ‘an apple pie’, and would have associated it with affection, fondness and yearning.

![Hans Christian Andersen and Frederick Warne and Co. Illus. Alfred W. Cooper. Our Favourite Nursery Tales: With Full Page Illustrations on Every Alternate Page. London: Frederick Warne and Co., [1883?], p.15 Nineteenth Century Collections Online](http://blog.gale.cengage.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Apple-Pie-poem-1024x757.jpg)

‘Apple Pie Sunday’, The Daily Mail, 3 Oct 1997: 66, The Daily Mail Historical Archive 1896-2004

[1]Captain Bland, The northern atalantis: or, York spy. Displaying the secret intrigues and adventures of the Yorkshire gentry…The whole interspers’d with several diverting poetical amusements, among which is Apple-pye: or, Instructions to Nelly, a poem. Being a nice and perfect account of the origin, progress, art, and method, of that incomparable viand. London: printed for A. Baldwin, near the Oxford-Arms in Warwick-Lane, 1713, Eighteenth Century Collections Online

[2] ‘Surrey Theatre’, The Times, 28 December 1829; pg. 3, The Times Digital Archive, and ‘Multiple Classified Advertisements’, Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle, 27 December 1829, 19th Century UK Periodicals

[3]Hans Christian Andersen and Frederick Warne and Co. Illus. Alfred W. Cooper. Our Favourite Nursery Tales: With Full Page Illustrations on Every Alternate Page. London: Frederick Warne and Co., [1883?], p.15 Nineteenth Century Collections Online

[4] http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2011/feb/22/cornish-pasty-earns-protected-food-status

[5] “Miscellaneous.” Leed’s Times 21 Dec. 1861: 3. British Library Newspapers

[6] ‘How to Make, and Enjoy, a Cornish Pasty’, Cornishman 22 July 1880: 6. British Library Newspapers

[7] ‘Concerning the Pasty’, Cornishman 2 Jan. 1908: 6. British Library Newspapers

[8] “Kids’ Apple Pie.” Daily Mail 4 Oct. 1996: 70 Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004