With Australian Heritage Week nearly upon us (16 – 24 April), the following is a post concerning a particular perspective of Australian colonial history, being a perspective that can be researched in detail with Gale Primary Sources collections. It concerns Australia’s paradoxical relationship with England since 1788, as reflected within the pages of London’s Punch magazine and its Australian editions – most of which can be seen in Gale Primary Sources collections, Punch Historical Archive, 1841 – 1992 and 19th Century UK Periodicals.

The paradox is that from the time of its origins as an English penal settlement, Australia modelled itself on the motherland, adopting the same institutions and system of government and considering a strict observance of English manners and mores to be the only proper way of life. Yet at the same time nineteenth-century Australians indulged a contempt for all things English and there was a persistent push to shrug off the legal and cultural dependency. As mentioned, it is a paradox that is vividly illustrated in the contemporary editions of the London Punch and its colonial iterations.

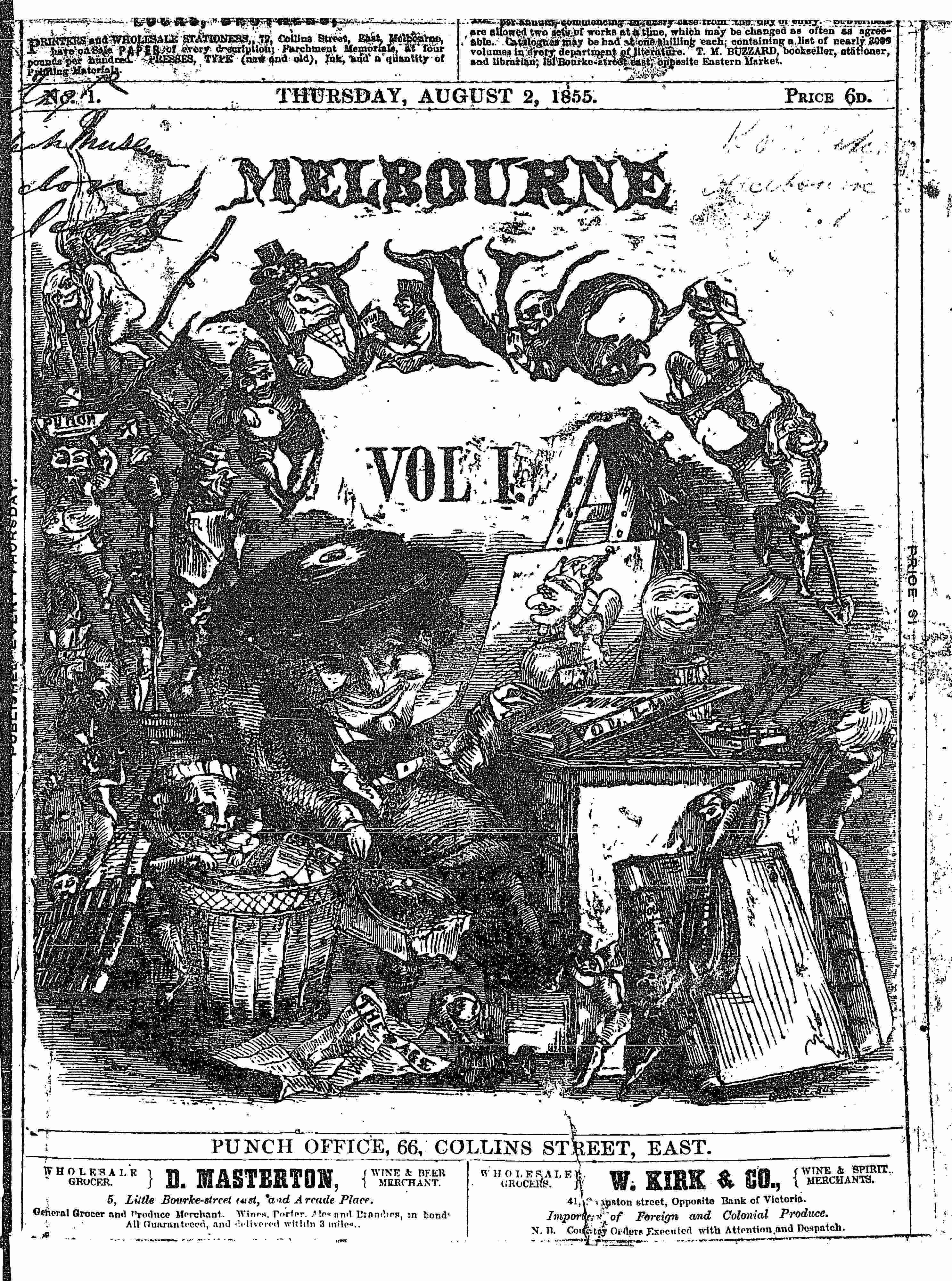

Punch originated in London in July 1841 and soon captivated English readers with its distinctive satire and political commentary, but despite copies also being shipped to Australia, locally-produced editions began to appear – Melbourne Punch began in August 1855; Sydney Punch started in May 1864; Adelaide Punch began in January 1878; and Queensland Punch started in 1885.

But these Australian versions of Punch are not what they first seem. In their title and format they present themselves as benign imitations of the London original. Even the editorial essay in the first issue of Melbourne Punch on 2 August 1855 describes the commencement of this publication with an analogy of a ship from Gravesend having recently docked in Melbourne, carrying its special passenger, “Mr. Punch Jun..” The actual work within these Australian editions, however, is hardly complimentary of England. Their journalism and illustrations are satirically critical of everything and anything to do with England and are brimming with anti-colonial angst.

English governors, for instance, are depicted as self-serving, having no true care for the people, and as impatient for their term of office to end so they can return home. An example of this is seen in the illustration in Melbourne Punch on 16 August 1855 showing Victoria House in Ballarat burning in the midst of the Eureka battles whilst Governor Hotham waits irascibly for his home-bound ship, saying ‘Let it burn, I’m only a lodger.’

The locals also took a quiet pride in their ability to survive and thrive in Australian conditions and were disdainful of newcomers from England who from head-to-toe appeared unsuited to their new country. As for the proud Australian, the illustrators of Melbourne Punch depicted him in the persona ‘Kangaroo Bull’, an uncompromising, forthright yet urbane figure, seen here laying down terms to his English landlord:

The newly-arrived Englishman, in contrast, was portrayed in the persona ‘Newchamp Green,’ who in all situations was too timid of mind and delicate in constitution for life under the Australian sun, as seen in these examples from Melbourne Punch from 1855:

The tension between Australia and England is evident even in the lives and careers of the illustrators who worked for Melbourne Punch themselves. The illustrator from 1886, for instance, himself English born and trained, came to Australia with the name Francis Thomas Dean Carrington before settling in Australia for ‘Tom’. During his initial years with Melbourne Punch he was criticised for being too much of an imitator of the style of the English illustrator, John Tenniel, although he subsequently developed a style more his own, and more Australian. So too, at least to an extent, did Melbourne Punch itself. From 1900 it dropped the word ‘Melbourne’ from its title.

These are some of the ways in which the Australian editions of Punch manifested the paradox in Australia’s attitude towards England. They were publications that gave full vent to the rebellious Australian spirit, yet that spirit, by the Australians’ own choosing, was all contained with this English framework.

The archive of the London Punch has been digitised in Gale’s Punch Historical Archive, 1841 – 1992. Gale has also digitised two of the Australian editions – Melbourne Punch from 1855 to 1920 and Queensland Punch from 1878 – 1893 – and these are to be found in the Gale Primary Sources collection, 19th Century UK Periodicals. The question that must therefore be asked are: how did these anti-colonial Australian publications come to reside in a Collection entitled ‘UK’ periodicals? The Australian editions were digitised from copies held in the British Library as part of a much larger project that consisted almost entirely of British periodicals! The only way these Australians editions could be digitised, then, was as part of this project in collaboration with the British Library.

For more information about the digital resources featured in this artice, or to request a trial, please get in touch with us today.