| By Rebecca Chiew and Emery Pan, Editors in the Gale Asia Publishing Team |

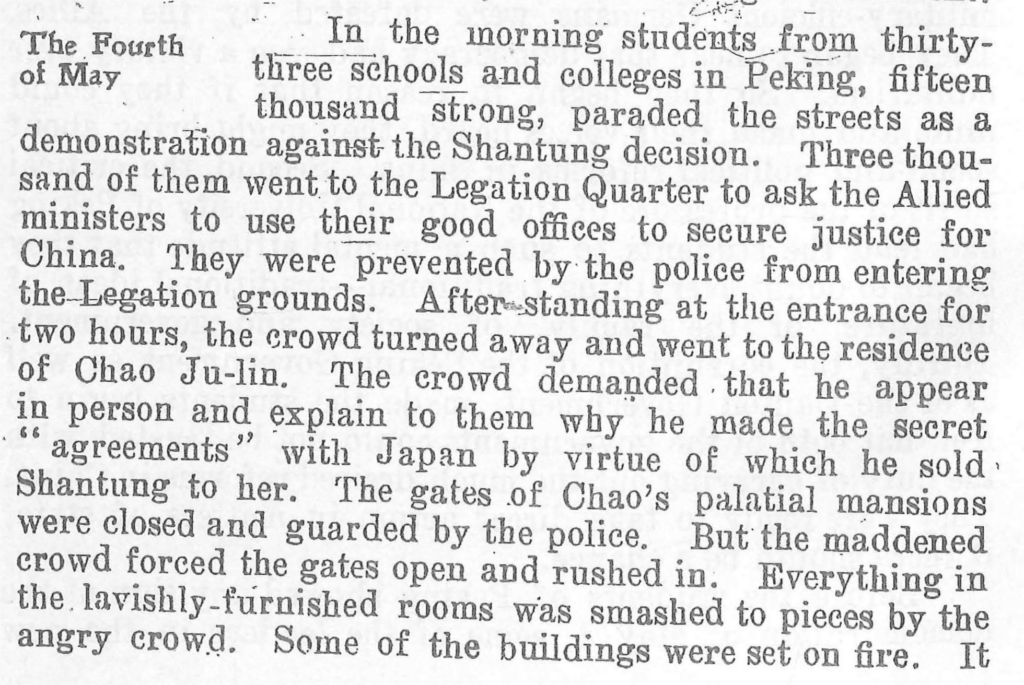

May 4, 1919 was a day to remember for Chiang Monlin (蒋梦麟), a senior member of the Peking University administration. Three thousand students from Peking University and more than a dozen other universities in Beijing demonstrated in Tiananmen Square against the upcoming signing of the Treaty of Versailles. Chiang went on to write The China Mission Year Book (1919) and in the chapter dedicated to “The Student Movement,” he offered a gripping account of the incident at Tiananmen, detailing the fury and violence perpetrated by the students on the perceived traitors of China, and the countermeasures taken by the Chinese government on the riotous protestors. Chiang also analysed the causes of the May Fourth Movement, described the philosophy that underpinned the students’ mindset, and the societal changes that this philosophy brought about. Chiang later became the president of Peking University and the Minister of Education (1928–1930).

http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/TFMQBL642628997/GDCS?u=asiademo&sid=GDCS&xid=23edc384

In a piece entitled “The So-called Student Movement,” published in 1920 in The Far Eastern Review, Gerve Baronti wrote of the May Fourth Movement:

“The student movement as it is called, has an intellectual substratum and a surface of patriotism. Like most youthful movements it lacks systematic methods. However, if properly organized, considering its strong points, grit, doggedness and determination, it could be the greatest force in China for the exposition of Japanese camouflage.”

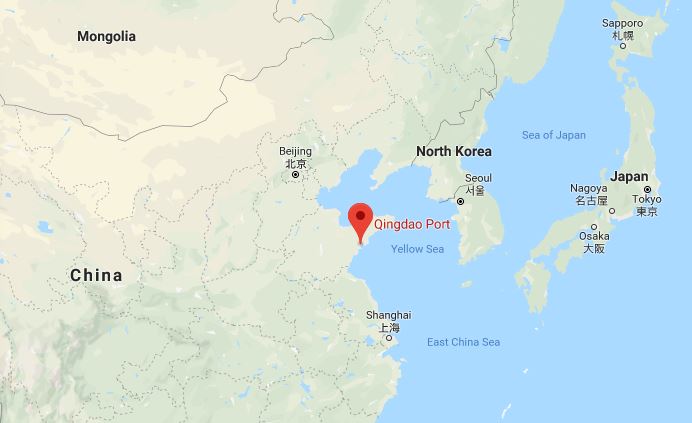

So, what fuelled these student protests? During WWI, Japan had engaged in expansionary military activities by declaring war against Germany and laying siege on the Port of Qingdao in the Shandong Province of China (see the port highlighted on the map below). Qingdao fell on November 7, 1914, after which the Japanese issued their Twenty-one Demands on China. Yuan Shikai, the President of the Republic of China at the time, capitulated to the demands on May 25, 1915. The Demands legitimised, among other things, the Japanese seizure and control of German ports and operations, and further expanded Japanese influence over transportation facilities in Shandong Province.

With the end of WWI and the victory of the Allies, the Chinese people, particularly the student intellectuals, saw a glimmer of hope. In their minds, the victory of the Allies would see the return of Chinese territories previously carved out as foreign concessions, and thus would reverse their century of humiliation. In particular, they were looking forward to regaining the Shandong Province (or the Kiautschou Bay Leased Territory, which became a German concession in 1898).

In the months leading up to the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, rumours were rife in China that the Chinese government would forfeit the Shandong Province to Japan at the signing ceremony. These rumours further fuelled the flames of anti-colonialism, particularly the strong anti-Japanese sentiment from the Chinese defeat during the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895).

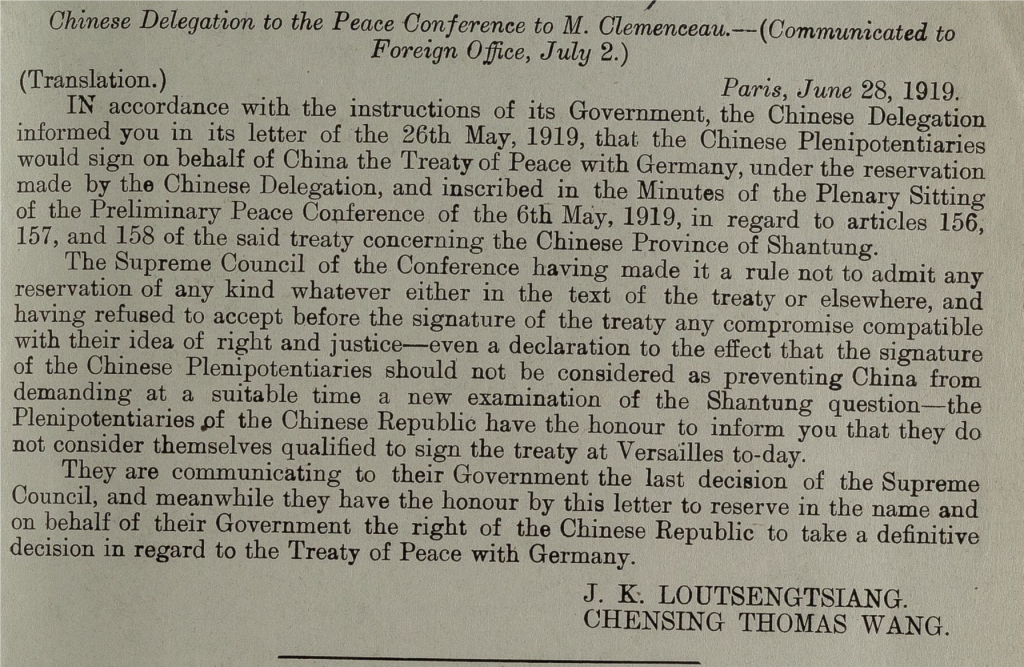

The Paris Peace Conference began on January 18, 1919. Foreign Minister Lou Tseng-Tsiang (陆征祥), who had signed one of the treaties resulting from the Twenty-one Demands, led the Chinese delegation, which also included other notable Chinese diplomats such as the Chinese Ambassador to France, Wellington Koo (顾维钧). As a result of the strong voice of opposition to the Treaty of Versailles which emanated from the Chinese populace—expressed via the students’ protests, and also actions such as strikes undertaken by businesses nationwide—the Chinese delegation to the Paris Peace Conference refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919. They were the only country who protested that day.

http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/9qou90

The wider impacts of the May Fourth Movement

Today marks the 100th anniversary of the May Fourth Movement. The May Fourth Movement was, however, far more than the student demonstration against the unfair treatment China received at the Paris Peace Conference; it had a far-reaching impact on China’s political development and cultural evolution in the first half of the twentieth century.

Politically, the Movement inspired Chinese nationalism and bolstered anti-imperialism, which led to a series of strikes in the 1920s and the eventual termination of foreign concessions in Shanghai and other treaty ports in the 1940s. Plus, the beginnings of the Communist Party of China can also be traced back to the Movement, as seen from the subsequent rise of student leaders such as Chen Duxiu (陈独秀) and Li Dazhao (李大钊) to leadership positions within the Party. Culturally, the Movement sparked off the New Culture Movement led by scholars and writers such as Dr Hu Shih (胡适) and Lu Xun (鲁迅) and witnessed the ascendance of the Chinese vernacular as an acceptable literary language.

In the seven decades from the first Opium War (1840–1842) to the early years of the Republic of China, China had experienced repeated defeats in her confrontations with the Western powers, resulting in the signing of various unequal treaties that infringed on China’s territorial and economic sovereignty. Following in the steps of the constitutional reformers and ‘self-strengtheners’ of the last years of the Qing Dynasty, the May Fourth Movement represented a new wave of effort by Chinese intellectuals to find ways to save and revive the country. They drew inspiration from various Western concepts such as democracy, science, anarchism, socialism, liberalism, idealism, pragmatism, materialism, and before long, Marxism. (See a review by Richard Harris of The May Fourth Movement by Chow Tse-Tsung, in the Times Literary Supplement, April 1961.) Many of these young participants later became believers of Marxism, having played a central role in reshaping China’s political landscape.

As explained by Ying-shih Yu in ‘The Radicalization of China in the Twentieth Century,’ a piece available in Gale’s Biography in Context database:

“May Fourth intellectuals’ early conversion to Marxism was certainly made much easier by their deep faith in ‘science’ in its extreme positivistic sense. The very term ‘scientific socialism’ carried with it a weight of authority which must have crushed many resisting wills. In this connection, mention may also be made of the enormous and long-enduring influence of social Darwinism. It paved the way for the wholehearted acceptance by May Fourth intellectuals of the Marxist iron law of social evolution as self-evident truth.”

The Movement also led to a series of industrial strikes and protests that played out in the 1920s and 1930s aiming to end colonial influence in China, including the concessions and settlements established by the Western powers since the 1840s. One comment from The China Critic in 1946 perfectly describes the political impact of the May Fourth Movement: “Though it was a movement of the students, it had become a movement of and for the people.” Borrowing the words of Chiang Monlin again, “Young China has become discontented with the old ways of living and old modes of thinking. She is now looking forward to a new and richer life.”

Aside from the political repercussions, this movement also initiated a cultural renaissance. One salient aspect of this renaissance lies in the fall of classical Chinese and the rise of modern Chinese. Here a name must be mentioned: Dr. Hu Shih, a US-trained philosopher. Hu is also known as a prominent diplomat and essayist.

As the leader of the New Culture Movement, an offspring of the broad May Fourth Movement, Hu advocated the use of pei hua, vernacular Chinese, in replacement of the aged literary style, known as Wen Yen or classical Chinese. In a chapter entitled “The Chinese Renaissance,” written by Hu in The China Year Book, 1924–5, Hu asserted that “the classical language was openly declared to have outlived its usefulness and have been the fundamental cause of the utter poverty of literary masterpieces during the past twenty centuries,” and that “the pei hua was shown to be the legitimate heir to the classical language.”

Thanks to the New Culture Movement, pei hua has become the official language of China since 1920. This has also contributed directly to the birth of modern Chinese literature. (See source below: “The Influence of Western Culture on Modern Chinese Literature”).

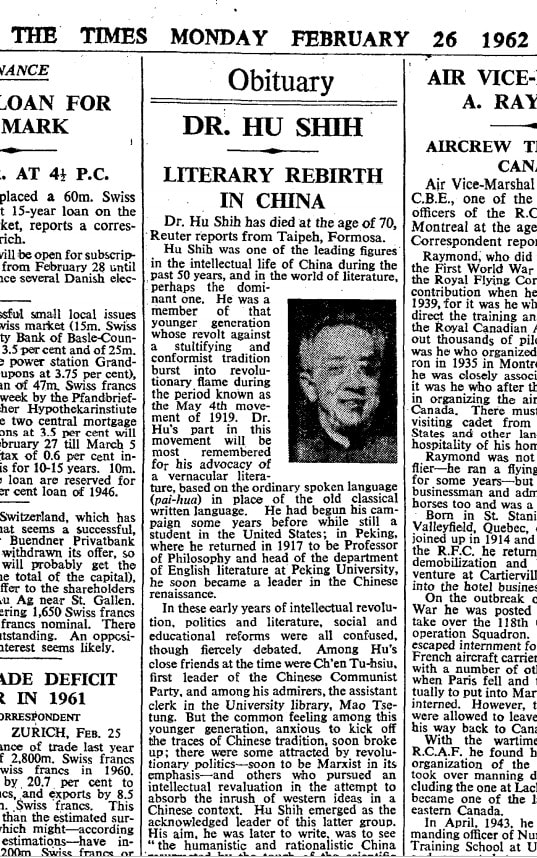

Hu passed away in 1962 and an obituary was published in the Times:

As Charles Dickens says in A Tale of Two Cities, “it was the best of the times, it was the worst of the times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness.” In the midst of the social and political instability and uncertainty of the early twentieth century, China infused her young intellectuals with a belief in unlimited possibilities. Amidst this world of darkness, China and her people managed to chart a path toward modernisation, as epitomised by the epochal May Fourth Movement.

Blog post cover image citation: 中文: 立北京大学的游行队伍Protestors at the May Fourth Movement, dissatisfied with Article 156 of the Treaty of Versailles for China (Shandong Problem), 4 May 1919, 图说五四:五四抗议活动 (3/17) [Public domain] Wikimedia commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Beijing_students_protesting_the_Treaty_of_Versailles_(May_4,_1919).jpg