By Anna Sikora, Gale Ambassador at NUI Galway*

In 2017, thousands took part in far-right marches on National Independence Day in Poland. My Irish friend asked me how worried we should be about the rise of far-right nationalism in Poland, my home country. He had seen newspaper headlines describing millions of Polish people, including school children and families, celebrating November 11 as “unsavoury.” I was shocked and disappointed; disappointed by hooligans disrupting the Independence Day marches, and shocked by the foreign media using images of these hooligans to represent the whole nation. This year has also seen heightened tensions, with attempts to ban far-right rallies and pleas from President Andrzej Duda for marchers to “come only with red-and-white flags,” rather than the nationalist banners and flags of far-right parties seen previously.

Since the fall of Communism in Europe in 1989, November 11 was re-established as a national holiday, known thereof as National Independence Day, and millions of Poles remember that on November 11, 1918, Poland regained its physical presence on the world’s map. In 1795, Poland had suffered its third Partition and the country, already sliced up in 1772 and 1793 by Prussia, the Habsburg Austria Empire and Russia, disappeared for 123 years, forcing such notable figures as Frederic Chopin, Adam Mickiewicz and later Joseph Conrad into exile, mainly in France and Great Britain.

I began wondering about the representation of these events as they happened, and, as I embarked on my research, I stumbled upon letters and monographs that shed an incredible light on the partitions, but from the perspective of the invading powers. The 572-page long volume titled The life of Catharine II. Empress of Russia. With eleven elegant portraits, … The fourth edition, with great additions, and a copious index. In three volumes, now accessible through Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online, provides a detailed analysis of the empress’ reign and her invasion of Poland.

Appendix No.VIII taken from the above and titled “Manifesto of the Empress of all the Russias relative to the Partition of Poland” tells us that “some unworthy Poles, enemies to their country, have not been ashamed to approve the government of the ungodly rebels in the Kingdom of France” (486), all while defying the wishes of “[h]er imperial majesty” and her “endeavours to maintain peace and freedom” (486) on the lands she usurped.

Aside from this highly specialised historical primary material, Gale Primary Sources allows me to view what the press had to say about the events in Poland. The Times reported frequently on the partitions, and the article “New Partition Of Poland”, published in 1792 after the Second Partition, tells us of Catherine the Great but from an entirely different perspective than the one presented in the manifesto above. The empress, we learn, “unmolested will hunt the prey and prepare it for carving. The patriotism and the courage of the Poles will, it is to be feared, avail but little against the formidable armies of an Imperial woman, whose ambition is insatiable, although near the grasp of that unrelenting tyrant of tyrants, Death. Then 3 feet by 6 of earth will be her portion.”

A week later, The Times published “The Amsterdam Gazette represents the PARTITION OF POLAND as a matter fixed on,” which engaged with another article published previously in The Amsterdam Gazette. As with the previous piece, the bias clearly sways towards Poland, represented here as a progressive and peaceful, but one who “will not escape the rigorous destiny prepared for her in silence by her jealous neighbours.” The article also mentions the Polish Constitution of 1791 which “merited the astonishment of all Europe” and which was the first modern constitution in Europe.

In 1795, after the Third Partition, The Times, The Courier, and London Packet or New Evening Post all reprinted an article published in the Paris Paper, as they all referred to it. The original article expresses outrage against the partitions calling it “barbarous and immoral,” yet not only against Poland but also the whole of Europe, which must now consider “this monstrous violation of all that is sacred.”

Similar articles proliferated, such as the one published in The Times in 1795. The article informs “with regret” about the last Partition of Poland “which reflects so much disgrace of the EMPRESS OF RUSSIA and KING OF PRUSSIA.”

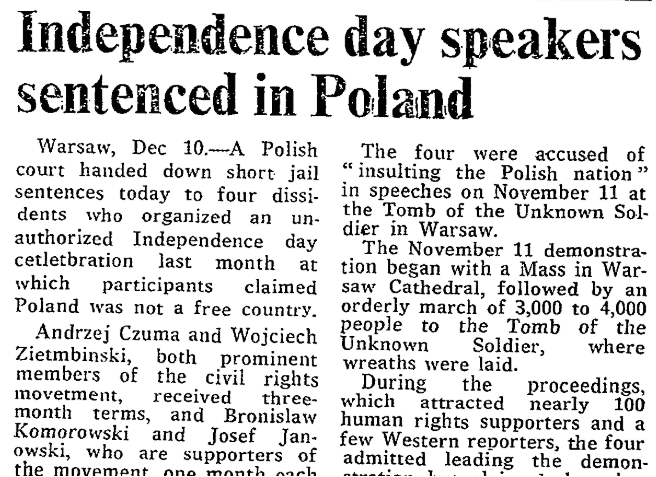

On the 11th of November 1918, the world celebrated the end of World War I, and Poland her short-lived independence. Just over two decades later, in 1939, Hitler attacked Poland from the west, and two weeks later, Stalin invaded from the east. The occupation lasted six years, and six million Polish citizens perished, including 3 million Jews and 3 million ethnic Poles. In 1945 World War II ended, but for Poland, another occupation began: a long 44 years of Soviet influence and a ban on celebrating November 11. The article titled “Independence day speakers sentenced in Poland” published in The Times 1979 describes how Polish anti-communist activists (including Bronislaw Komorowski, later President of Poland) received jail sentences for celebrating Independence Day.

The rise of Solidarność (Solidarity) in Poland headed by Lech Wałęsa (later President of Poland) contributed to the crumbling of communism in 1989, and today millions can freely celebrate National Independence Day without fear of political repercussions.

*Anna was part of a previous cohort of Gale Ambassadors at NUI Galway.

Bibliography

Castéra, Jean-Henri. The life of Catharine II. Empress of Russia. With eleven elegant portraits, … The fourth edition, with great additions, and a copious index. In three volumes. … Vol. 3, printed by A. Strahan, for T. N. Longman and O. Rees, 1800. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZFbnX. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.

“Independence day speakers sentenced in Poland.” Times, 11 Dec. 1979, p. 5. The Times Digital Archive, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZMDU7. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.

“It is with regret, we again allude to the laƒt PARTITION of POLAND, which reflects so much disgrace.” Times, 24 Dec. 1795, p. 2. The Times Digital Archive, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZGrq0. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.

“New Partition Of Poland.” Times, 21 June 1792, p. 3. The Times Digital Archive, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZFaK5. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.

“News.” Courier, 22 Dec. 1795. 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZFao0. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.

“News.” London Packet or New Evening Post, December 21, 1795 – December 23, 1795. 17th and 18th Century Burney Collection, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZFbE1. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.

“Partition Of Poland.” Times, 23 Dec. 1795, p. 3. The Times Digital Archive, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZFaG0. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.

“The Amsterdam Gazette represents the PARTITION OF POLAND as a matter fixed on. The.” Times, 29 June 1792, p. 3. The Times Digital Archive, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5ZFaV2. Accessed 26 Nov. 2017.