By Rebecca Bowden, Associate Acquisitions Editor

If one was researching current affairs, political history, or a particular literary period, Gale Primary Sources would be an obvious place to look. It is full of useful archives, from newspapers like The Times and The Independent, to huge collections of diverse primary sources, such as Nineteenth Century Collections Online. But what if you were researching something altogether more obscure – say, palmistry, feng shui or crystal therapy? It may surprise you that Gale Primary Sources continues to shine!

Let us take crystal therapy as an example. First, Gale Primary Sources can be used to establish what crystal therapy is, and how it is perceived by the medical community. In Civilization, The Magazine of the Library of Congress, found in Gale’s Political Extremism and Radicalism archive, Robin Marantz Henig writes:

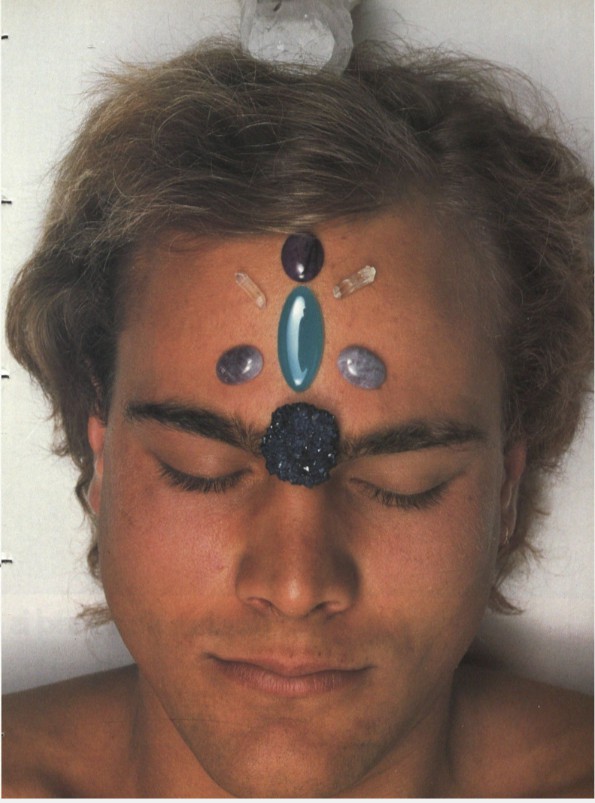

‘Crystal healing is based on the belief that mineral crystals contain healing energy. Practitioners lay crystals on their patient’s bodies to relax them and to get their physical vibrations in tune.’

There is little scientific evidence to indicate that crystal healing actually works. An article in The Times states that ‘while there is a significant amount of anecdotal evidence for crystal healing, I have not been able to uncover any clinical research into it.’ That being said, ‘just because we do not understand how something works, does not mean that it cannot work.’ Indeed in an article in Smithsonian Collections Online, Richard Gerber, author of Vibrational Medicine, suggests that:

‘We know from Einsteinian theory that all matter is basically energy…quartz crystals apparently produce a subtle energy field that escapes measurement by traditional electro-magnetic devices, but is nonetheless capable of influencing biological organisms.’

This belief is followed so far by some that crystal healing has been used in prisons to help prisoners ‘come to terms with stress and internal pain.’ Articles from 1996 in both The Telegraph and Archives of Sexuality & Gender report on the use of crystal therapy in prisons in the UK and USA. They indicate that ‘prisoners with little faith in traditional health care have apparently greeted the project with enthusiasm.’ It is interesting that these unproven methods were being employed on both sides of the pond.

Organization: Prison Fellowship. December 15-22, 1996. MS International Vertical Files from the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives ID: 7921. Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives. Archives of Sexuality & Gender, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/79gNj4. Accessed 5 Oct. 2018.

So, Gale Primary Sources can help one come to a decent understanding of what crystal therapy is. But what about if I have decided to put the scientific uncertainties of the treatment aside, and embark on my own crystal healing journey? What can Gale Primary Sources tell me now?

Firstly, it is important to know that different crystals have different properties. Agate, the International Herald Tribune archive tells us, slows the pulse and stops insomnia; Amber holds calming and energising properties; while Rose Quartz heals emotional wounds and rejuvenates the skin. An article in Archives of Sexuality & Gender takes this even further, reporting that it is because of its association with the heart chakra (both are pink) that it can be used to heal the heart. Quartz, one of the most common New Age crystals, amplifies intuition, transforms an imbalanced energy field and revitalises you when you are feeling stressed, according to The Sunday Times. One issue of Goddess Rising, a magazine found in Archives of Sexuality & Gender, devotes almost an entire page to the properties of Tourmaline, ‘a stone [that] comes in different colors and is a solar stone which attracts inspiration, and bestows self-confidence and joy of life.’

Clearly, then, I must be careful in choosing my crystals to ensure that I get the most out of them. Let us imagine I have chosen Quartz – after all, sitting at my desk writing this, I could always afford a little extra clarity…

Now, what should I do with my crystals? I’ve found two sources in Gale’s Political Extremism and Radicalism archive which provide me with directions. The first, and probably the most straightforward, suggests I make a crystal garden, in which crystals that are more than an inch in length can be stood upright in white sand in an earthen bowl. This is, I am told, ‘not only a beautiful way to store them when you are not using them in ceremonies, but the garden itself can be used as a meditation focus.’ It goes on to indicate that ‘a simple, yet powerful arrangement…is to place one in the centre and the other four equidistant from it and each other’ – these can then correspond to each of the five elements (Earth, Air, Fire, Water and Spirit). Selena Fox, the author of the piece, leaves me with one final piece of advice: ‘be sure to listen to your own Inner Self and to the crystals themselves,’ when selecting an arrangement.

The second article I found (p.426) offers a completely different approach. Here, the crystals are made into bowls, because ‘the power of positive intention or affirmation combined with the music of crystal bowls provides remarkable healing results.’ To play the bowls, you strike them with rubber mallets or suede covered wands, hitting the outside of the bowl, near the rim and following the sound around the bowl to enhance the length and volume of the note. I am also warned not to put my head in the bowl while playing it – presumably a shattered eardrum rather ruins the healing effect! Perhaps unsurprisingly the author attempts to sell such crystal bowls at the end of the article, and they’re $119-$350. Crystal gardens appear cheaper, and certainly more accessible, to the beginner.

Finally, Shelley von Stunckel, writing for The Sunday Times, warns me that ‘because crystals collect energy, they must be cleansed from time to time.’ Washing them in spring water or burying them in sea salt will do the trick, so long as I throw away the salt afterwards.

To some, crystal therapy is just New Age rubbish that has no basis in science and so should be disregarded completely. Yet crystal therapy, and other homeopathic remedies, are slowly creeping back into the millennial psyche – increasingly Instagram is filled with pictures of immaculate interiors, dotted with gemstones and accompanied by captions detailing their therapeutic uses. This is not the place for an analysis of their resurgence in popularity, but perhaps the simplest explanation is that they are beautiful objects in and of themselves – certainly worthy of display. Do we really lose much if their medical claims turn out to be false? And if they do work, well then, all the better. Regardless of whether you put any stock in it or not, it is interesting to look into the background of these traditions, and to gain an insight into something you might previously have known nothing about. It also goes to show that Gale’s archives can be useful in unexpected ways – I have not made myself a crystal garden yet, but thanks to Gale Primary Sources, I now know how.