By Daniel Mercieca, Gale Ambassador at Durham University

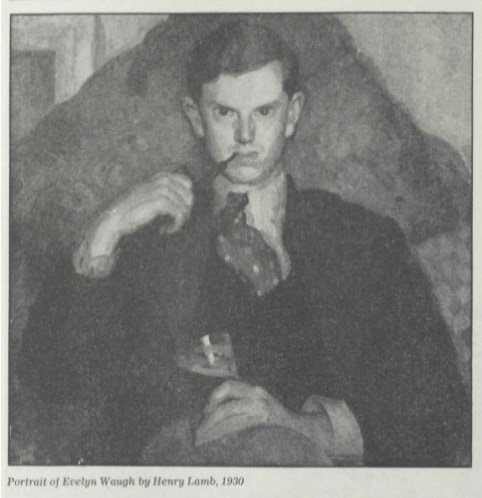

Evelyn Waugh is best known today for his delicately crafted satirical novels of the 1930s including Decline and Fall, Vile Bodies and Scoop. Only in Waugh do you find such precise comic timing and snappy diction: “Who’s that dear, dim, drunk little man?’ ‘That is the person who shot my son.’ ‘My dear, how too shattering for you. Not dead, I hope?” (Decline and Fall).

Waugh was also a prolific correspondent for The Daily Mail and The Sunday Telegraph from 1930–1963. Gale Primary Sources, which includes the historical archives of both papers, illuminates how Waugh’s satirical eye and sharp prose interrelates with the colourful world of his novels.

‘Not Very Drunk-making’

The giddy, cocktail-fuelled parties of the interwar generation were the prime target of Waugh’s satire, starring the wild and radiant ‘Bright Young Things’. Waugh himself was part of this set during the 1930s, delighting in drinking heavily until the early hours of the morning at various parties and nightclubs in London.

Waugh’s characters are known for their extravagant slang which bled into his novels from the social circles encompassing him, as evidenced in his April 1930 article ‘I Prefer London’s Night Life’. Waugh’s criticism of Parisian nightlife – paying ‘two hundred francs for disagreeable or very ill-making champagne’ and having to ‘gump’ between establishments – bears a strong correlation to the antics of Agatha Runclible’s set in Vile Bodies. As in the novel, the ‘Bright Young Things’ appear entertaining, but also childishly tragic in their hedonism.

How too too meta.

Waugh, Evelyn. “I Prefer London’s Night Life.” Daily Mail, 5 Apr. 1930, p. 10. Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/5WFVbX.

‘To Prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet’

Waugh was not a self-proclaimed modernist, but the dislocated sentences and fragmented paragraphing of his novels faintly echo the stylistics of T.S. Eliot and his sordid rendition of urban life. What makes Waugh particularly innovative is his adaptation of modern technology, including telephone conversations, cinematic transitions and newspaper typology. Throughout Waugh’s novels, ‘The Excess’ and ‘The Daily Beast’ pun on the print as a comedic lens on the shallowness and gluttony of the so-called lost generation.

Waugh’s August 1930 article ‘The Old Familiar Faces’, is written with similar whirling semi-colons and subtle semantic field of a ‘black background’ to frenetic passages depicting the nihilism of ‘Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties… All that succession and repetition of massed humanity… those vile bodies.’ Waugh’s formatting of italics, capitalisation and his own footnotes in Vile Bodies is akin to the prosaic texture of his own newspaper columns; his detached narrative voices in unison with his journalistic tones, ridiculing society for its cycle of aimless celebrations.

Waugh, Evelyn. “The Old Familiar Faces.” Daily Mail, 2 Aug. 1930, p. 8. Daily Mail Historical Archive, 1896-2004, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/55v6P3.

‘A Medium Revisited’

Playing with fiction and reality and blending his characters as portraits of people in his own coterie is what made Waugh’s comedy so sensationally comical and disorientating. The humour is still as rich today. Once you finish reading a Waugh novel, you will find that some characters pop-up again in the background of his next publication, continuing to live their extravagant lives as comic asides. The infamous Margot Metroland manages to make an appearance in seven of Waugh’s novels; her final appearance, along with that of Basil Seal and Peter Beste-Chetwynd, even extends to the print of The Sunday Telegraph as a serialised short story.

Waugh, Evelyn. “Basil Seal Rides Again.” Sunday Telegraph, 10 Feb. 1963, p. 4+. The Telegraph Historical Archive, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/55v74X.

Amongst the novels’ gossip columns, drunk diction and hallucinogenic visions of Agatha Runcible (Vile Bodies) and Tony Last (A Handful of Dust), Waugh extended his fiction to the cartoonist’s plain. In a Dickensian vein, Waugh’s novels are peppered with his own hand-drawn sketches, visualising his one-dimensional characters and even mythologising the figure of Captain Grimes.

The Telegraph Historical Archive contains Waugh’s original cover illustrations for the Oxford Broom (a student paper for which he contributed as an undergraduate at Hertford College, Oxford). The amalgamated design of unicorns and contorted limbs neatly prefigures his disjointed plots, lost characters and blending of Carrollian fantasy with his novels’ depiction of modern society.

Waugh, Evelyn. “An Author’s Yesterday.” Illustrated London News, 3 Oct. 1964, p. 503. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/55ziA5.

Gale Primary Sources enables us to investigate the relationship between Waugh’s fiction and his writing as a journalist in terms of technique, aesthetic and political commentary. Just as Waugh experimented with cross-pollinating literary mediums, this blog demonstrates the benefits of analysing fiction with digital archive material in the twenty-first century.

I wonder what Waugh would have made of this blog as a new medium.

Probably quite vile.