│By Eleanor Leese, Acquisitions Editor, Gale Primary Sources│

If, like me, you frequently find yourself wondering what David Bowie would be up to if his time with us mortals hadn’t been so tragically short – last week we got some answers. The BBC reported that David Bowie spent his last months deep in research about eighteenth-century Britain.

The appeal of the eighteenth century is something we know a little about here at Gale Primary Sources, as publishers of Eighteenth Century Collections Online, the largest collection of digital primary sources emerging from that century which is shortly to receive a large additional module in the form of ECCO, Part III. So, of course, the first thing that I did after learning about Bowie’s interest in our favourite historical era was to set about looking for the sources he had been reading. I wanted to see if I could find what had captured his imagination and ECCO did not disappoint.

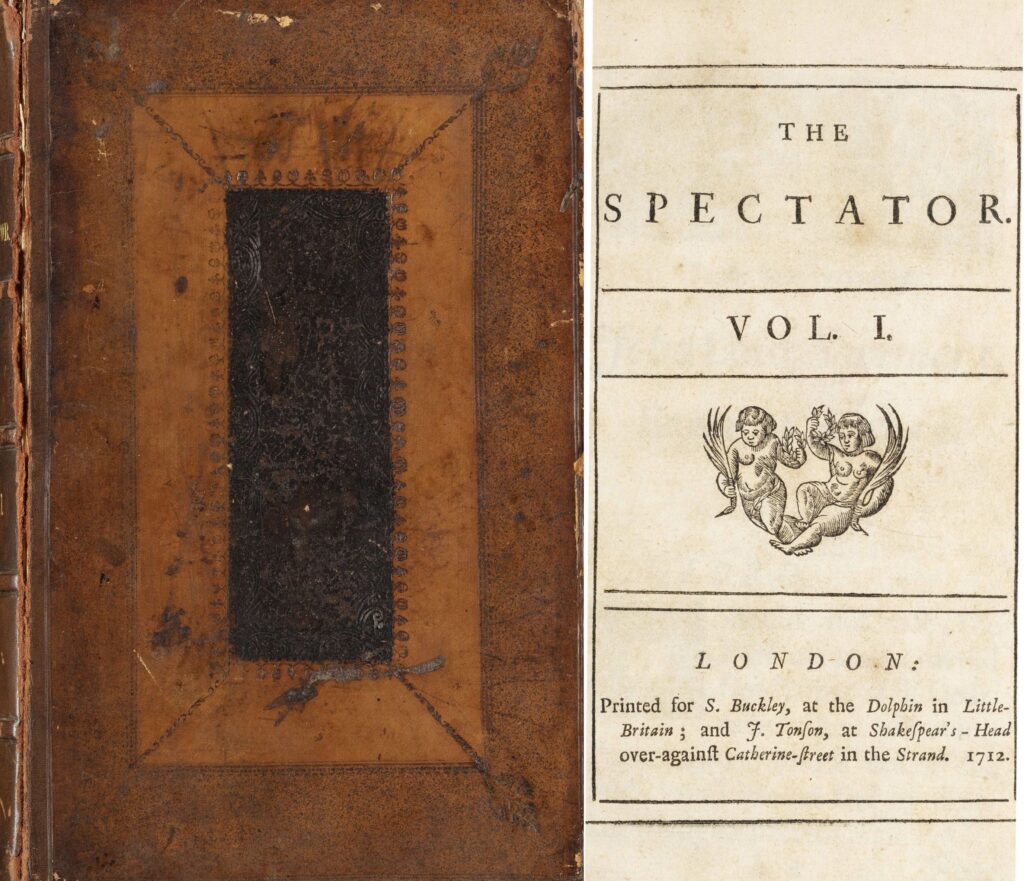

The Spectator

One of the primary sources that Bowie seemed to be most interested in was The Spectator (not the same publication as the current Spectator). This was a daily news sheet published in 1711 and 1712, and David Bowie had a dedicated notebook for this one source. ECCO already has several volumes of The Spectator in Parts I and II. But what I was really excited to find was that this beautiful leatherbound version will be appearing in ECCO, Part III (and you can find it in the trial version of the archive now).

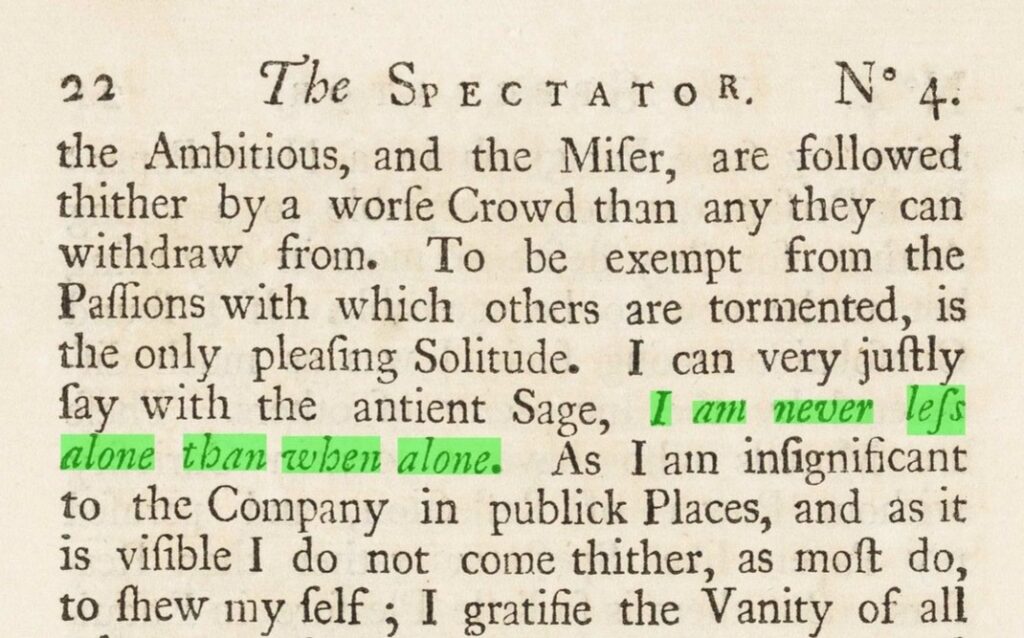

Using the keyword search, I was even able to find one of the lines that Bowie had handwritten onto a sticky note:

The breadth and depth of Bowie’s understanding of the period is astonishing. As well as detailed timelines for key artistic influences of the era, he also had a clear understanding of the currents of social change that were a hallmark of the century. His notes appear to reference the burning of Newgate Gaol, the Gordon Riots, and even the earthquake that shook London, both physically and psychologically, in 1750.

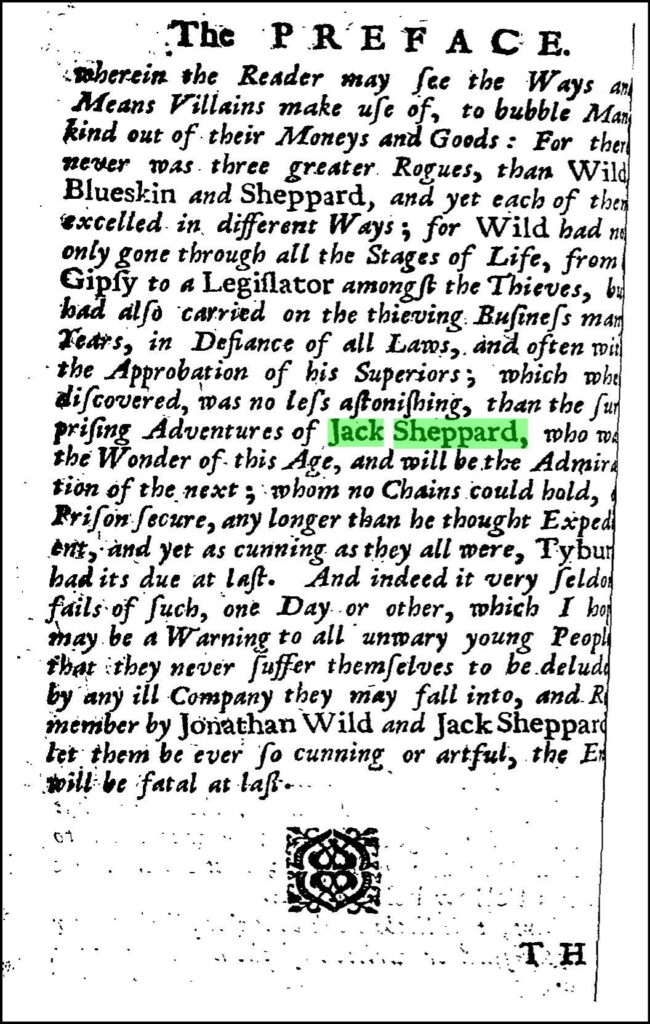

The Infamous Jack Sheppard

One name that recurs in many of Bowie’s notes is Jack Sheppard, an (in)famous criminal who appears no less than thirty-eight times in ECCO Parts I and II. According to one account of his life, Sheppard was a career criminal, convicted of theft and sentenced to death in 1724. He was to be held at Newgate until his execution, but, undeterred, Jack Sheppard broke the spikes from the window of the room where he was kept and escaped with the help of ‘two ladies of [his] acquaintance’.

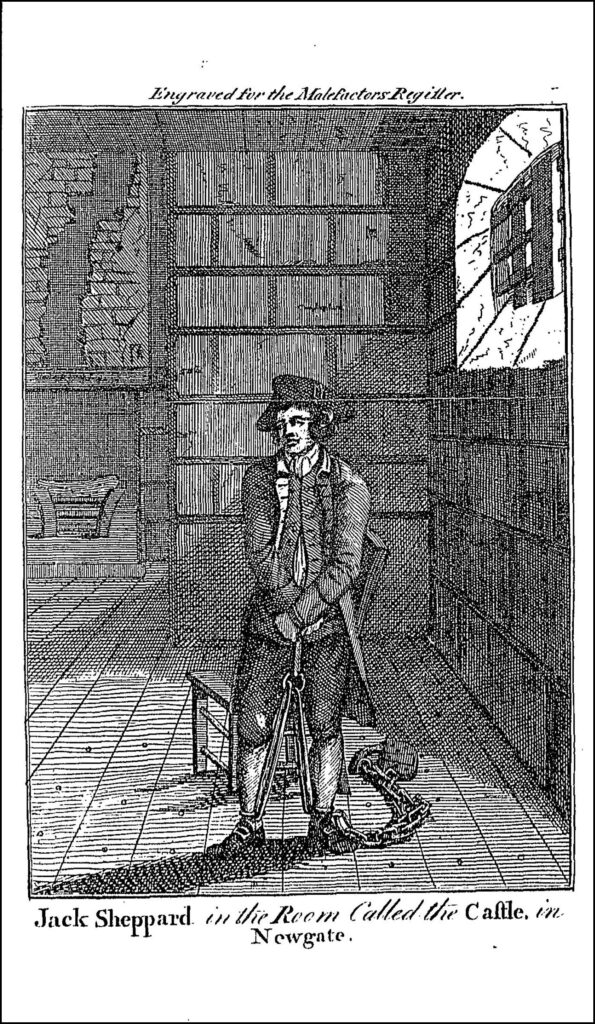

He was soon apprehended again, and this time was held in ‘the castle’, where he was ‘hand-cuffed, loaded with a heavy pair of irons, and chained to a staple fixed in the floor’. Unfortunately, the guards failed to spot a small nail left in the room, which Sheppard used to unlock his hand cuffs.

His subsequent escape is remarkable for the variety and ingenuity of the methods he employed. He broke an iron bar away from inside a chimney stack. He smashed through doors with brute strength, forced locks, and, when he reached the final door between himself and the outside world, simply slid open the bolt.

He found himself on the roof of Newgate Gaol, still in irons, and in the pitch black darkness. He jumped to a neighbouring house and waited for a couple of hours in the attic, before eventually creeping downstairs when the family were asleep.

Several days later, having lost the irons, and wearing the finest apparel he could steal from a pawnbroker, he headed back towards Newgate, bought his mother a brandy, and eventually got so intoxicated he was returned to the gaol, despite carrying two pistols and a sword.

By this time Sheppard was infamous across the country, and he was never short of visitors. However, despite asking any nobleman who visited him to intercede with the king, the sentence of death was passed once more. There was to be no escape this time. Sheppard was executed at Tyburn on November 16, 1724, after guards confiscated the penknife he had hidden in his pocket.

An Inspiring Century

It’s impossible not to wonder what David Bowie made of the lurid true crime accounts that described Sheppard’s crimes. And what are we to make of Bowie’s interest in a man who was described as being ‘the Wonder of this Age, and will be the Admiration of the next; whom no Chains could hold, no Prison secure’?

We can never know what would have come of Bowie’s research – I, for one, will spend the rest of my life wondering about his note that reads simply ‘many sex scenes’.

But Bowie’s interest in the period only goes to show the richness of the sources that survive from this period, and the powerful stories they can be used to tell. For those of us working with Eighteenth Century Collections Online, it’s both moving and exhilarating to see a true visionary inspired and captivated by this revolutionary century.

If you enjoyed reading about eighteenth-century Britain, then check out these posts:

- Digitisation as a Catalyst for Conservation

- An Eighteenth-Century Intersectional Feminist? Exploring the Life of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in Eighteenth Century Collections Online

- Who was the Chevalier de Saint-Georges?

Blog post cover image citation: A montage of images from this blog post, combined with a photo of David Bowie’s star on the Hollywood walk of fame, courtesy of @sara_the_freek on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/photos/david-bowie-star-JIbTSKqnews