│By Lucy McCormick, Gale Ambassador at the University of Birmingham│

The Daily Mirror began life in 1903 as a journal for respectable women – a burgeoning demographic at the fin-de-siècle, to whom the major daily newspapers did not cater. It launched staffed by women and pursued a female (although not exclusively) readership. Adrian Bingham’s article for Gale is a fascinating exploration of the Daily Mirror’s relationship with women. Building upon this rich contextual knowledge, this blog stresses the significance of this venture to embolden female readers and female writers in the androcentric tabloid press.

How did the Mirror depict women? Why did Arthur Harmsworth centralise women in his newspaper? How did women forge new roles for themselves as journalists and readers? This Women’s History Month, we are delving into Gale’s archive of the Mirror from 1903 to find out more.

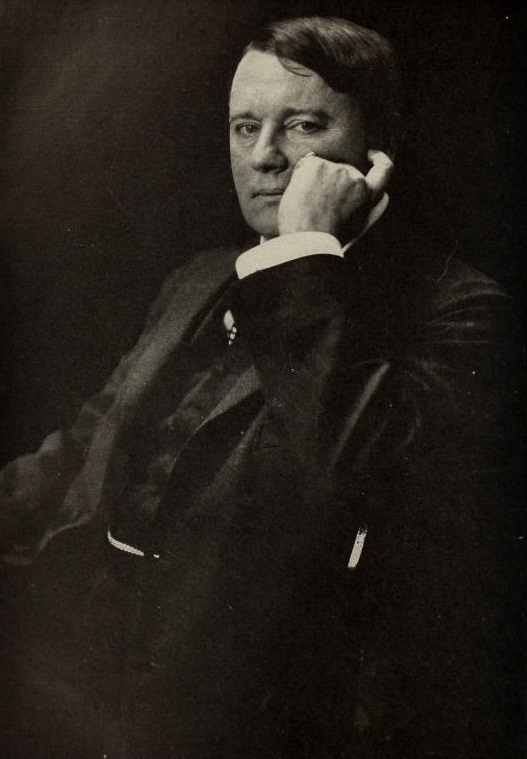

Harmsworth’s Intentions

How was the Mirror engineered to serve women as both writers and readers? To answer this question, we need only go so far as the first article in the very first issue from November 1903, in which founder Alfred Harmsworth (1865-1922) explicated the purpose of his newspaper:

“… it represents in journalism a development that is entirely new and modern in the world… It is no mere bulletin of fashion, but a reflection of women’s interests, women’s thought, women’s work. The sane and healthy occupations of domestic life, the developments of art and science in the design and arrangements of the homes of all classes, the daily news of the world, the interests of literature and art – these will all be found equally represented beside those more intimate matters in which (fortunately for the decoration of this dull world) women still take an interest.”

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Alfred_Harmsworth,_1st_Viscount_Northcliffe.jpg

Owing to the expansion of women’s freedoms and education around the turn of the century, it had ‘only recently’ become ‘necessary’ and ‘possible for me to find the large staff of cultivated, able, and experienced women’ to orchestrate this ‘feminine’ paper. Harmondsworth believed its subjects to be ‘surely as important to the world as those of finance, ship ping [sic], and sport’, all of which already received plenty of attention in the daily newspapers which were the lifeblood of the national press.

Editor Mary Howarth (c.1858-c.1934) pointed out: ‘The life, the organisation, the politics of the family; of each little dominion within four walls where a woman is queen, has hitherto received expression from month to month, from week to week, but never till now from day to day’.

Harmsworth lamented the absence of the ‘feminine’ perspective in public discourse. Indeed, he capitalised on the nascent demographic of educated women, to whose interests no daily newspaper afforded much attention. Yet Harmsworth’s ‘reflection’ reveals a more ambitious intention – to hold up ‘a mirror on feminine life’ and render this engaging to the mass readership. It was not just about filling a gap in the market, but rather offering a new approach to journalism altogether.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EWFTDW180317976/DMIR?u=bham_uk&sid=bookmark-DMIR&xid=471773b9

Mary Howarth

The first editor of the Daily Mirror, Mary Howarth was instrumental in shaping the newspaper and women’s relationship to it. Howarth’s journalism was daring in its scope and unflinching in its scrutinising gaze. Her articles ranged from ‘Memories of a Visit to Montenegro’s Capital’, to a celebration of ‘Women Who Lead Double Lives’ by ‘running a business and keeping a home’, to ‘New Fashions in Womanly Grace’, in which Howarth ‘shows us how patriotic service has improved the beauty of women’ after the First World War.

The ambitious breadth of Howarth’s journalism reveals that women were licensed to commentate on a growing range of issues and thereby stake their claim in popular discourse; they were producers as well as consumers. Furthermore, journalists such as Howarth were emboldened to set the agenda of national conversations. No longer was their writing relegated to marginal periodicals – their ideas and opinions were emblazoned on the pages of a mainstream national tabloid.

The New Woman

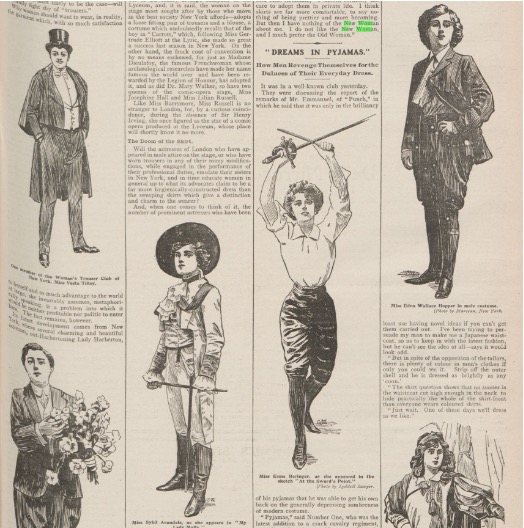

The New Woman was a trope in popular culture which poked fun at women’s pursuit of liberty. Caricatured as a bespectacled, university-educated, bloomer-wearing cyclist, she emblematised the threat the women’s movement posed to rigid gender roles and the social stability they ostensibly provided. A journalistic invention, the New Woman was a hot topic of debate in the early twentieth century – and the Mirror regularly featured it to stir public opinion.

The Daily Mirror often affirmed that real women were averse to this trope. An article about ‘The Woman’s Trouser Club’ in New York quoted an actress who, despite wearing men’s clothes on stage, protested that ‘I have nothing of the New Woman about me. I do not like the New Woman’.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IIZWYR694397806/DMIR?u=bham_uk&sid=bookmark-DMIR&xid=e7977869

Another article, provocatively titled ‘“New Woman” No Longer Exists’, ‘a Reformed “New Woman”’ chided the ‘new-woman gospel’ as a ‘fashionable fad’. Women were ‘wildly excited’ by prospects of independence, suffrage, and smoking cigarettes, but merely ‘commandeers the freedom of a man without assuming any of his responsibilities’. She declared that ‘there has never been such a failure in any social movement as in the so-called “emancipation of woman”’ because ‘[t]he mass of women never wanted’ a vote and ‘never will achieve it’.

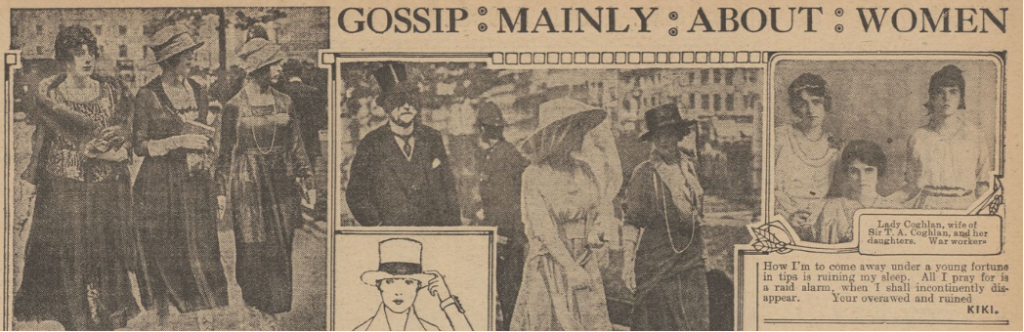

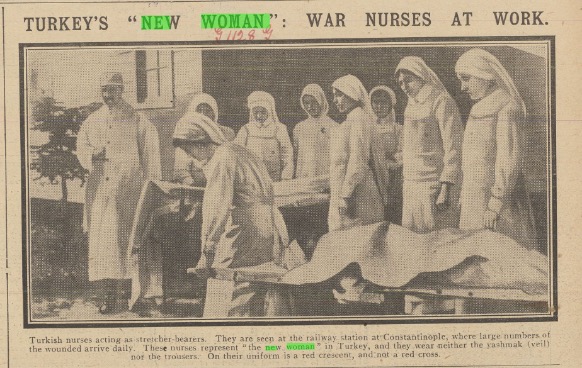

Nevertheless, the Mirror consistently offered its readers a variety of perspectives on the New Woman. Its journalists also extolled the Queen of Italy as ‘a new woman in the best sense of the term’ and commended as ‘a perfect type’ the ‘New New-Woman’ who served as a nurse during the War.

The Mirror’s journalists did not impose one perspective upon their readers, in the expectation that they were passive receptacles of opinion, but rather purposively offered contesting opinions on issues which affected women. In so doing, the Mirror helped cultivate an informed and engaged female readership, thereby bolstering their presence in the British tabloid tradition. The relationship between female writers and readers was therefore a symbiotic one.

The Mirror for Historians

The Mirror did not initially prove a financial success, owing to competition from illustrated papers and technological developments in rotary printing. The paper was overhauled and its all-female staff disbanded, rendering this journalistic experiment short-lived.

Nonetheless, this period of the Mirror’s history, in which female authors wrote for female readers, calls for greater historical attention. This blog has sought to pique interest and provoke questions, inviting you to delve into Gale’s archive of the Mirror from 1903 to 2000 and discover more about women’s relationship with this pillar of the British press.

If you enjoyed reading about women and the Mirror, check out these posts:

- The Influence of British Media on its Politics: Insights from Gale Primary Sources

- Using Gale Historical Newspapers to Highlight Marginalised Voices in Journalism

- Using Literary Sources to Research Late Nineteenth-Century British Feminism

Cover Image: A montage of images from this blog post, combined with “Daily Mirror.” Daily Mirror, 2 Nov. 1903, p. [1]. Mirror Historical Archive, 1903-2000 https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HJJKWB634981818/DMIR?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-DMIR&xid=f876d122