│By Lucy McCormick, Gale Ambassador at the University of Birmingham│

Earlier this year, Gale launched History of Disabilities: Disabilities in Society, Seventeenth to Twentieth Century – a rich digital archive of monographs, manuscripts, and ephemera, sourced from the New York Academy of Medicine. This offers countless avenues for exciting historical research. To provide an example, this blog will focus on homes for disabled girls in early twentieth-century Britain, aiming to demonstrate the value of Gale’s sources to help us learn about attitudes towards disability in the past.

Content Advisory

Context

Throughout the nineteenth century, the medical establishment, government, and society conceived punitive ways to confine disabled people. For instance, the 1834 Poor Law Act sent disabled people to workhouses in which they endured brutal working and living conditions. With the emergence of the welfare state, increasing attention from social reformers, and philanthropic efforts, provisions and attitudes towards disability looked different in the early twentieth century. Some aspects of this were forward-thinking, others discriminatory.

Children’s experiences within this context are often difficult to trace, but we can look to reports from those new institutions to learn more.

St. Catherine’s Home for Crippled Girls

Its annual reports reveal that St. Catherine’s was founded in Croydon in 1910 “to provide a home and employment for several crippled girls”. Describing its resident children as ‘inmates’ and ‘cripples’, St. Catherine’s employed the derogatory language of its nineteenth-century predecessors. These young women “contribute[d] towards their support by doing fine sewing, embroidery, drawn thread work, crotchet, initials, monograms, and fancy work of all kinds”. Had much changed since the workhouse?

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AAFWEV289001270/HODI?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-HODI&xid=418a3976&pg=30

Perhaps we see the ethos of the nascent welfare state materialise. From the 1912 annual report, we learn more about the children: one of the nine residents was an amputee, and the home “provide[d] her with an artificial limb, so that she can now walk without crutches. Another girl with a paralysed leg has been supplied with a new splint and high boot”.

Unlike its Victorian precedents, St. Catherine’s took pride in the support it gave to these children. St. Catherine’s trained young women in marketable skills, whilst also providing care and accommodation. The relics of disparaging nineteenth-century language clash with the benevolence of their actions; St. Catherine’s seems to emblematise the ambiguity and mutability of attitudes towards disability in early twentieth-century Britain.

The Watercress and Flower Girls’ Christian Mission

The Watercress and Flower Girls’ Christian Mission offers another interesting example of those changing attitudes:

“The State has undertaken the education of the children, the protection of the helpless child, and the clearing of the streets of the child hawker, and great and beneficial as the result has been to the Nation, there still however remains, neglected and suffering, untouched by the State, the crippled, maimed, and afflicted child, made so by disease, accident, or cruelty, found on crutches in the streets, or lying on the doorsteps in the slums, or, worse still, in the cellars or garrets”. (Forty-Third Annual Report of the Watercress and Flower Girls’ Christian Mission, p.12.)

Flower girls were a common sight on the streets of early twentieth-century London. Often orphans, young girls prepared bunches of flowers or watercress to sell to passersby. Philanthropist John Groom established what he called a ‘crippleage’ – an orphanage for these girls, many of whom were disabled. He trained them to craft artificial flowers (a fashion of the time) or to enter domestic service.

The Forty-Third Annual Report informs us that the Mission was comprised of several branches, including an “orphanage home for little waif girls”, a “holiday home for blind and crippled girls”, and a “crippleage and sanatorium”. It boasted that the “flower-making branch now trains and employs nearly 300 maimed, blind, and crippled girls”.

Much like St. Catherine’s, it is evident that benevolent intentions drove such efforts: Groom’s orphanage proudly declared that its “staff is devoted to its work, and the inmates show by their healthy and happy condition the advantages of these Homes to them”. However, it is difficult for the twenty-first-century reader to look past the disparaging language used to describe disabled children.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AFQVHR928055312/HODI?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-HODI&xid=79f909ec&pg=301

These sources bring to light the complex issues which arise when researching the history of disability, serving as an important reminder of the necessity of grappling with the changing implications of language over time.

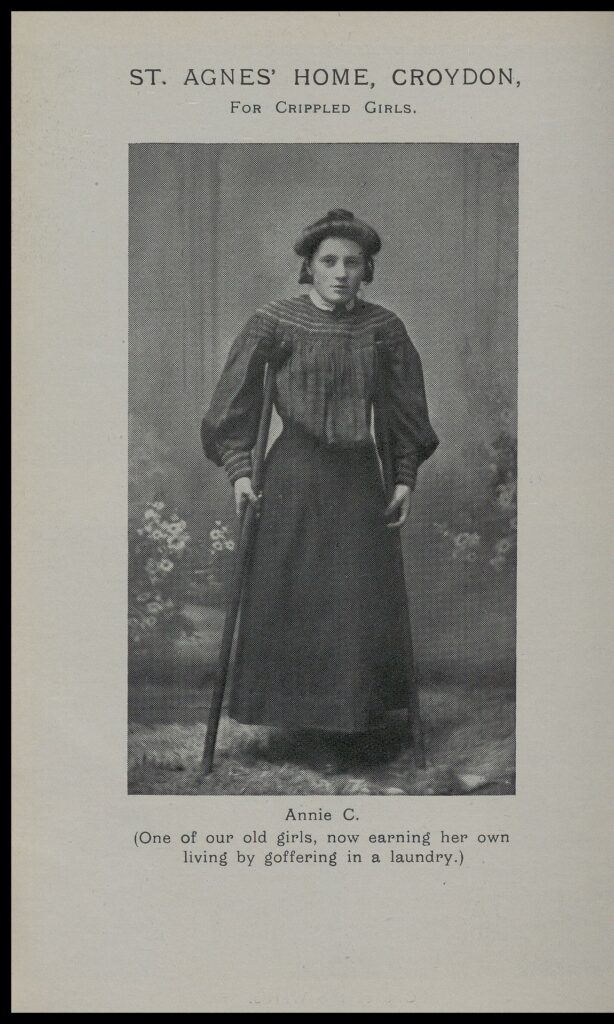

St. Agnes’ Home for Crippled Girls

The 1911 Annual Report of the Children’s Union reviewed the operations of St. Agnes’ Home for Crippled Girls in Croydon. This source is especially valuable because it enlivens the stories of individual children. Following her residency at St. Agnes’, “Ethel H. has gone to live with her brother and is able to earn money by doing plain needlework and giving lessons in basket-making”. We also learn about Dora, who has become a dormitory maid, and Helen, a domestic servant.

Although this source does not offer first-hand accounts from those children, it does afford a rich insight into their lives; it does not homogenise these girls’ experiences, but instead affords importance to their individual stories.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AFQVHR928055312/HODI?u=bham_uk&sid=bookmark-HODI&xid=41526ec8&pg=288

Conclusion

If we are to challenge language and attitudes towards disability in the present, it is important to do so in historical contexts too. Studying sources like these enables us to understand where language and ideas came from.

The girls discussed in this blog were marginalised in their own historical moment and have been afforded little attention in the historical record. This new Gale archive prompts us to contemplate their experiences and perspectives and realise the power of historical attention.

With thanks to Phil Virta, the editor overseeing History of Disabilities, for his guidance using this archive.

If you enjoyed reading about the history of disability and women’s history, check out these posts:

- Uncovering a History of Disabilities: Disabilities in Society, Seventeenth to Twentieth Century

- Tracing the Young Women’s Christian Association through Women’s Studies Archive: Female Forerunners Worldwide

- Using Literary Sources to Research Late Nineteenth-Century British Feminism

Cover image: Residents at John Groom’s so-called ‘crippleage’, an orphanage for girls who sold flowers on the streets of London around the turn of the twentieth century. McMurtrie Volume K104 McM. 1908-1915. MS Douglas C. McMurtrie Cripples Collection. New York Academy of Medicine. History of Disabilities https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/AMDOFR202227628/HODI?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-HODI&xid=f77622bc&pg=176