│By Ellen Grace Lesser, Gale Ambassador at the University of Exeter│

The famous wizarding twins Fred and George Weasley first introduced patents to me, explaining them to be the legal right granted to an inventor to prevent others from copying their invention. State Papers Online taught me that patents can be more than that: they are the official and legal conferring of a right or a title of any kind to anyone for a set period of time. In practice, this means that as long as a right or a title is temporarily conferred to a named entity (whether that be an individual person or a company) the right is a patent. It was interesting to discover that patents do not necessarily have to apply to inventions. While looking into the State Papers Online archive, I discovered many other kinds of patents as well as patents for inventions. From the contents of the patents to the physicality of the documents, I will share with you three of the patents I found in the archives and why each is interesting in a different way.

1. The Patent of the Dragon-Slayer

History is full of weird and wonderful stories and I discovered one such story hidden in a patent within State Papers Online.

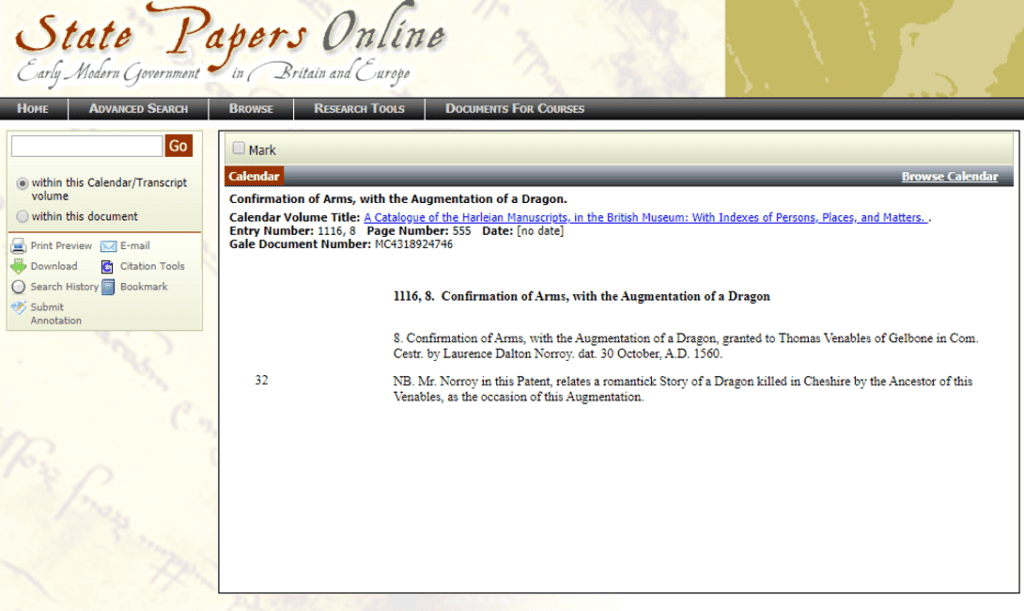

The patent below comes from a catalogue of the Harleian Manuscripts kept by the British Museum, a catalogue which was edited by Robert Nares, Stebbing Shaw, Joseph Planta, Francis Douce and T. H. Horne. The patent itself describes a fairly mundane occurrence: on October 30, 1560, Thomas Venables was granted a confirmation of arms – that is, the arms which Venables already owned were confirmed. This occasion was noted with “the Augmentation of a Dragon” – that is, the addition of a dragon to the Venables coat of arms.

So far, so average. One might not even question too much the reason for the addition of a dragon over any other heraldic symbols. However, Laurence Dalton Norroy, the individual confirming the arms, was determined to justify the Venables’ connection with dragons. In a note describing the contents of the manuscript, the editors of the catalogue wrote: “Mr. Norroy in this Patent, relates a romantick Story of a Dragon killed in Cheshire by the Ancestor of this Venables, as the occasion of this Augmentation.” This patent is not just the confirmation of arms, therefore, it also includes Norroy’s retelling of Thomas Venables’ ancestor, a supposed dragon-slayer. Whether you believe the tale or not, it has truly stood the test of time, for there remains a dragon on the Venables coat of arms to this very day.

http://go.gale.com/mss/i.do?&id=GALE%7CMC4318924746&v=2.1&u=exeter&it=r&p=SPOL&sw=w&viewtype=Calendar. Gale Document Number: MC4319824746.

2. The Patent Out of Order

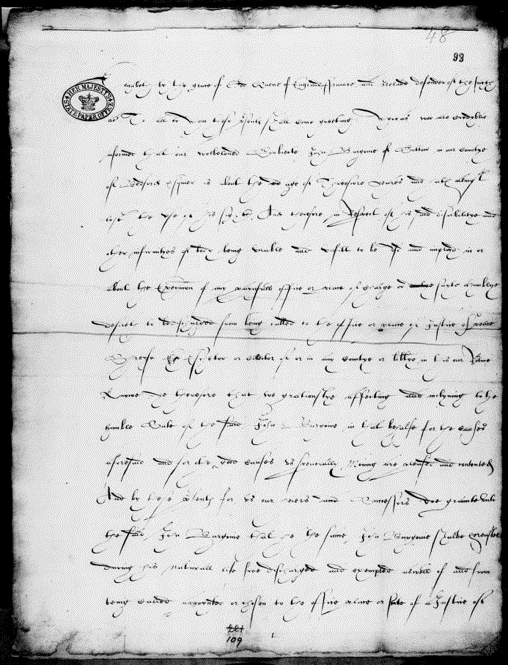

What I found interesting about the second patent I want to share was not so much its contents, but the document itself. This patent describes the exemption of one John Burgoine from several political duties, namely: “justice of the peace, sheriff, escheator, and collector”. Furthermore, it states that Burgoine was not to be fined for his not participating in these duties. It is not explicitly stated exactly why Burgoine was being exempted from these duties, but it is implied that there were two factors at play: Burgoine’s age (he was 60 at the time) and his disability (he was blind). Whatever the reason for Burgoine’s exemption, my interest in this manuscript was held mainly by the physicality of the document. Gale’s primary sources are photographed and scanned, so that the original document is visible online to the user:

What drew my attention is that the manuscript of Burgoine’s patent has been physically changed prior to scanning. This manuscript comes from a collection and you can clearly see the alteration of the page numbers at the bottom of each page.

This is a reminder that archival documents have two stories to them: the story of their original creation (in this case, the exemption of John Burgoine from political duties and any resulting fines) and the story of their existence through time (in this case, their inclusion in this collection and the physical alteration of the page numbers).

Edits, alterations and quirks in the physicality of documents can take many different forms. One can clearly see, for example, the source below from Archives of Sexuality and Gender has been folded in half, leading me to think about who did this, when, and why they were using the document in this way.

3. The Patent of the Secret Recipe

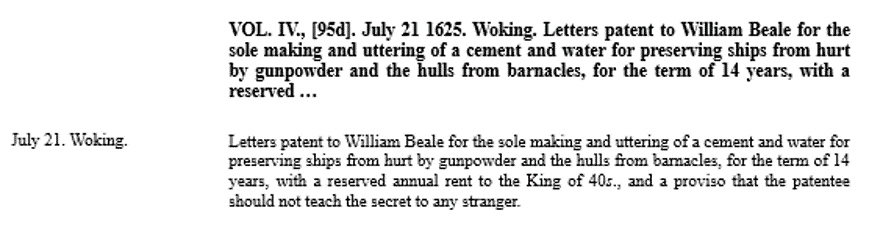

The third and final patent is the only one I will be looking at in this blog post that pertains to an invention or product – though it is by no means the only one of this kind I found in State Papers Online! The patent, from 1625 and belonging to one William Beale, pertains to a nautical invention: a kind of cement which can protect ships from both enemy cannon fire and from damage wrought by barnacles to the hull:

This granted the inventor the sole right to prevent anyone else from reproducing the invention. There is a caveat, however: the patent becomes null and void if the inventor were to share the cement recipe with anyone else. This begs the question: why? Perhaps it is because of the product’s clear military applications. It also begs the question of how well such an enforcement could really be policed. Either way, this ship-protecting cement was treated much like the recipes of famed products such as Coca-Cola, and even the dishes served in some restaurants today – as a secret recipe to be protected, only this secret was being kept by royal command!

When I began delving into State Papers Online, I wasn’t sure what I would find. After limiting my search to patents I quickly came across far too many sources to discuss them all here, but all of them were fascinating! My biggest takeaway from this investigation was that documents of the same type can be interesting in very different ways – from their content, to their physicality, to the wider implications of their very existence. Delving into State Papers Online has broadened my understanding of what a patent is and made me very glad that, if I ever go to Cheshire, Thomas Venable’s ancestor has already sorted out any draconic menaces plaguing the county.

Want to read more about the fascinating sources in State Papers Online? Check out On Her Majesty’s’ Secret Service – Elizabeth I in the age of spies, or Here Comes the Sun King: finding Louis XIV in State Papers Online.

Blog post cover image citation: Harrison, Charles. “Farmers! Protect your Crops by Using ‘Bink’s Patent Futurist Scarecrow. ‘ Specially Designed by an Eminent Cubist. No Bird Has Ever Been Known to Go within Three Fields of It.” Punch, July 17, 1918, 33. Punch Historical Archive, 1841-1992 https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/ES700123883/GDCS?u=exeter&sid=GDCS&xid=02a17149