|By Liping Yang, Senior Manager, Academic Publishing, Gale Asia|

On the morning of August 9, 1965, a visibly shaken Lee Kuan Yew, prime minister of Singapore, stood before journalists and television cameras. His voice trembled and his eyes welled with tears when he talked about the moment when the agreement “which severed Singapore from Malaysia” was signed. For him, it was “a moment of anguish.” His words marked the beginning of a new chapter for Singapore—a moment that would redefine two nations.

Sixty years on, the emotional weight of that day still echoes through the region’s political and cultural memory. But what did ordinary people know at the time? How did newspapers report the unfolding crisis, and what voices emerged in the public sphere?

Thanks to the recent release of British Library Newspapers Part VII: Southeast Asia, 1807–1974, we now have unprecedented access to the press coverage of that era. This digital archive, comprising over 1.1 million pages from 36 English-language newspapers and periodicals published across Singapore, Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand, offers a rich tapestry of perspectives on colonial legacies, postcolonial aspirations, and regional upheavals.

In this post, I revisit the events surrounding Singapore’s secession through news articles. We will witness not only the political manoeuvring and ideological clashes that led to the split, but also the human stories of disappointment, resilience, and reconciliation that followed.

Background: Federation of Malaysia and Singapore’s Joining

After the end of World War II (WWII) in Southeast Asia, Peninsular Malaya experienced first the short-lived Malay Union of 1946-48, and then the Federation of Malaya. Both political entities consisted of nine Malay states and two Straits Settlements (Penang and Malacca) while Singapore remained separate as a British colony.

Until Malaya gained independence from Britain in August 1957, the Federation had been a protected self-governing colony of the United Kingdom. In September 1963, the Federation of Malaya joined Singapore, North Borneo (Sabah), and Sarawak to establish the Federation of Malaysia.

However, shortly before the Federation’s second anniversary celebration in 1965, Singapore withdrew, causing great dismay and grief among many Malaysians. In “The Challenges Ahead” and “Malaysia’s Eventful Years”(Sunday Gazette, August 29, 1965), the authors tried to cheer up the people by stressing the capability of Prime Minister Tunku Abdul Rahman to meet the various challenges lying ahead and Malaysia and Singapore governments’ readiness to cooperate.

Moreover, the young Federation celebrated many achievements, outperforming many other countries through policies like the first five-year development plan and the establishment of the Bank of Bumiputra to shore up the rural development programme.

All these happened in the context of confrontation mounted by Indonesia, “a giant aggressive neighbour.” The prime minister and deputy prime minister had successfully won the sympathy of many African countries and the support of the UK, Australia, and New Zealand by overcoming the propaganda campaigns launched by Indonesia and had also managed to repel the incursions of their army.

Yet, to fully understand the rupture, one must examine the deeper ideological and political rifts that emerged between the ruling coalition in Kuala Lumpur and the government of Singapore—differences that would ultimately prove irreconcilable.

Divided Minds and Visions on Malaysia

The Alliance Party was a political coalition formed in Malaysia in October 1957 after the independence of Malaya. Comprising the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA), and Malayan Indian Congress (MIC), it was the ruling coalition of Malaya from 1957 to 1963, and then of Malaysia from 1963 onward.

The Alliance Party in Malaya and the People’s Action Party (PAP) led by Mr Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore showed glaring differences in their understanding of and visions for Malaysia. The Alliance Party, especially the UMNO, strongly advocated for special rights and preferential policies towards the Malay community. In comparison, the PAP and Lee Kuan Yew argued that Malaysia must be run according to its democratic constitution, aiming to establish a fair and equal country.

To deal with the aggressive central government that had generated “growing concern among us because of [its] racial and communal bent,” PAP decided to forge a united front with non-Malay parties in the Peninsula, Sarawak and Sabah. On May 9, 1965, the Malaysian Solidary Convention (MSC) came into being, consisting of the People’s Action Party from Singapore, the United Democratic Party and the People’s Progressive Party from Peninsula Malaysia, the Sarawak United People’s Party, and the Machinda Party from Sarawak.

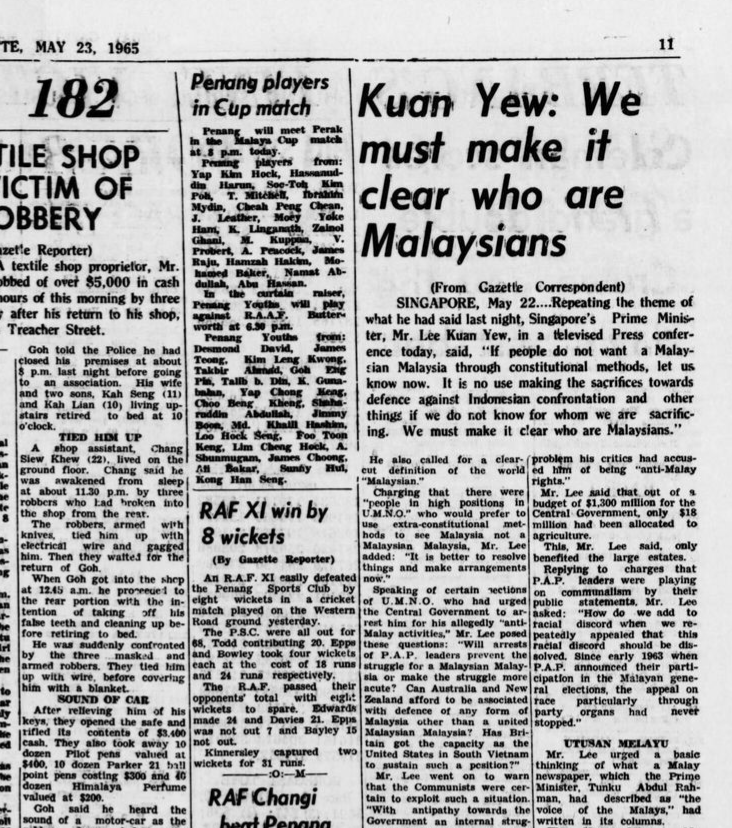

The MSC campaigned for the concept of building a “Malaysian Malaysia” versus “Malay Malaysia.” In a televised press conference of May 22, 1965, Lee Kuan Yew called for a clear definition of “Malaysians.” He pointed out that some “people in high positions in UMNO” wanted to “use extra-constitutional methods to see Malaysia not a Malaysian Malaysia” but a “Malay Malaysia.” PAP leaders “could never give way to a ‘Malay Malaysia’ or other kind of Malaysia other than a Malaysian Malaysia.” He held that the government should consider “whether we can uplift [the rural and poor] Malays and raise their earning capacity.”

In a speech Lee Kuan Yew declared that “unless there was a Malaysian Malaysia…then there would be disaster.” He challenged the Alliance “to compete for popular support on the basis of policies that they had to improve the lot of the peoples of Malaysia.” At the same time, he was disappointed that the King “did not reassure the nation that Malaysia would continue to progress in accordance with its democratic constitution towards a Malaysian Malaysia but on the contrary added doubts on the intention of the Alliance Government.”

The MSC, PAP, and Lee Kuan Yew’s advocacy for “Malaysian Malaysia” and criticisms of UMNO’s commitment to Malay supremacy had met with strong counter attacks from the Alliance Party. Tan Siew Sin, finance minister cum chair of the Malayan Chinese Association (MCA), accused Lee of “taking a strong anti-Malay line” with the intention to “attract an adequate Chinese following in the States of Malaya” and “enable an over-ambitious politician [Lee Kuan Yew] to achieve supreme power.” All these would cause “racial strife.”

Extremist sections in the UMNO urged the arrest of Lee Kuan Yew for his alleged “anti-Malay activities” and called for the partition of Malaysia. To this, Dr Lim Chong Eu, MP and secretary-general of the United Democratic Party, a member of MSC, refuted that Lee never suggested for the partition of Malaysia in a speech carried in the Straits Times. This was nothing but distortion of facts and misquotations. It was described as part of the central government’s effort to “besmirch and jeopardize the healthy growth of a strong, loyal, and effective democratic opposition.”

A Moment of Anguish: Separation Declared

Given the escalating hostility between the Alliance Party and the PAP, their leaders began pondering the possibility of separation in order to avoid bloodshed. While attending the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ Conference in London in June 1965, the Tunku decided that separating Singapore from the Federation seemed to be the only choice.

After secret discussions and negotiations, an agreement of separation was signed on August 7. The announcement of Singapore’s separation or independence from the Federation was made in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur simultaneously on the morning of August 9, 1965.

Lee Kuan Yew called a press conference in Singapore to explain the inevitability of the separation. With his eyes brimming with tears, Lee said: “This moment when we signed this Agreement which severed Singapore from Malaysia, it will be a moment of anguish… because all my life … I have believed in merger and the unity of these two territories. You know, it’s a people connected by geography, economics and ties of kinship … Would you mind if we stop for a while?”

Reactions of Organisations and States

The announcement of the separation of Singapore from Malaysia prompted a spectrum of responses—from political disillusionment to cautious optimism—among states, parties, and individuals within the Federation.

The Malaysian Solidarity Convention was very disappointed with the departure of Singapore and promised, at a public rally in Penang on August 15, 1965, to continue their efforts toward building a Malaysian Malaysia by opposing “inequality and social injustices” and bringing “pressure of public opinion to bear on the Alliance Government” in the hope that the latter would rectify their mistakes and change their policy.

The separation had plunged the Borneo states—Sabah and Sarawak—into an unexpected political quandary. The main political parties there felt unhappy because they had never been informed beforehand of Singapore’s intention to withdraw. Some of them suggested a reexamination of the conditions of the two states’ entry into the federation, demanding more autonomy, or even going for an eventual secession.

How to keep Sarawak and Sabah within the Federation became a top priority for the central government. Prime Minister Rahman made a “tell the people” mission to the two states to assure them that they would not be asked to leave. At the same time, Finance Minister Tan Siew Sin promised in Parliament on November 11, 1965 to provide $300 million for their development.

While the Borneo States were displeased, Penang, especially its business community, felt rather optimistic. With Singapore out, the city looked set to become the largest free trade port in the Federation and therefore be able to play a crucial role for country-wide commerce.

Mutual Restrictions and Accusations

In the immediate aftermath of the separation, the two sides found themselves locked in a period of mutual suspicion and trade restrictions, as both sides struggled to redefine their new relationship. These had “almost ground the two-way trade to a halt,” causing a great stir among the commercial and industrial bodies on both sides of the causeway. The worsening relations also resulted from frequent exchange of hot words around the following issues:

Lee’s criticism of Malaysia’s political system

In a speech given on October 17, 1965, Lee Kuan Yew criticised Malaysia, referring to the latter as “a medieval feudal society” which is “bogged down by corruption.” This had drawn a strong protest from the Malaysian government. Both the Malaysian prime minister and deputy prime minister castigated Lee for his “wanton and uncalled for interference in the domestic affairs of Malaysia.”

Singapore’s barter trade with Indonesia

Malaysia and Singapore had one common adversary—Indonesia—due to the latter’s opposition to the Federation of Malaysia. Singapore sought to improve its relationship with Indonesia for the sake of survival. It restored the barter trade with Indonesia at a small island south of Singapore.

This infuriated Tunku Abdul Rahman who slammed Singapore for its failure to consult Malaysia first due to its potential impact on Malaysia’s national security: “It is a wrong thing for the Singapore Prime Minister to enter into any deal with Indonesia … The benefits which Singapore expects to derive from this deal is out of all proportions to the threat and to the survival of Malaysia and Singapore.”

Work permits and schools fees

Following the separation, Singapore faced a sudden and large influx of people from Malaysia, creating a pressure on the local job market. To protect Singapore citizens’ interests, the government decided to issue new identity cards, work permits, and raise the school fees for non-citizens. These were elaborated in President Yusof bin Ishak’s statement on Dec 8, 1965 at the first Parliamentary Session since Singapore’s Independence and Lee Kuan Yew’s speech given at a joint Chinese new year-Hari Raya celebration on January 30, 1966.

In response, Tunku Abdul Rahman criticised Singapore’s new policy of requiring non-citizens to apply for work permits, saying this would place Malaysian residents in Singapore “in a position… of almost being indentured labour” and making them “victims of the whims and fancies of their employers.”

For the Singapore leaders, the people of Singapore were their own masters and these attacks from across the causeway were unwelcome. Singapore Education Minister Enche Rahim Ishak appealed that “after independence was thrust upon us, all we want is to be left alone and look after our own interests.” Lee Kuan Yew also responded, saying that those people thought that “Singapore was a small island and could easily be coerced and controlled.” He declared that “Let history decide which side was right [or] wrong.”

Efforts To Repair and Restore the Relationship

As the dust began to settle, both governments recognised the need to explore avenues for reconciliation. According to Tunku Abdullah, leader of the Malaysian delegation to the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association Conference, the separation of Singapore “will make the heart grow fonder” because “we are basically one people and both sides are already saying we will unite.” The two governments also showed a “change of heart”, and agreed in December 1965 to “heal the breach” and “work on economic co-operation”.

As a gesture of goodwill, the Malaysian government also urged the members of Singapore UMNO to show “undivided loyalty to the local Singapore government and contribute to the welfare of the country” instead of opposing any communities there. Even the hawkish finance minister Tan Siew Sin said that the two sides were trying their best to “reach agreement on a common currency arrangement” and be friends again.

These remedial measures undertaken by both sides helped ease the tensions caused by the separation and laid the foundation for a complex yet enduring bilateral relationship—encompassing trade, investment, and tourism—that continues to hold relevance today.

Happy birthday, Singapore!

If you enjoyed reading about the separation of Singapore, you may like to read the following posts:

- The History of West Malaysia and Singapore as Refracted Through British Colonial Office Files

- Decolonisation in the British Empire in Asia: The Malayan Emergency and Singapore

- Tracing the History of Malaysia, Singapore, and Hong Kong through British Official and Non-Official Documents

Blog post cover image citation: A selection of images from British Library Newspapers Part VII: Southeast Asia, 1807–1974