│By Leila Marhamati, Associate Editor, Gale Primary Sources│

Maybe “Intersectional Feminist” is taking it a bit far, but Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762) has certainly been described as a woman ahead of her time. Best known today for the correspondence she maintained while traveling with her husband through the Ottoman Empire from 1716 to 1718, Lady Mary was commonly on the fringes of and often at the forefront of major historical developments in Britain and the Western world. She provided startlingly positive views on non-Western cultures and scientific experimentation at a time when both were viewed with suspicion. And yet, she was still located within a society that embraced hierarchical institutions and systems of oppression.

Using Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), we can trace these many aspects of Lady Mary and, through them, glean insights into the eighteenth century as a whole. This post contains some documents from the forthcoming release Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Part III, available in March 2026.

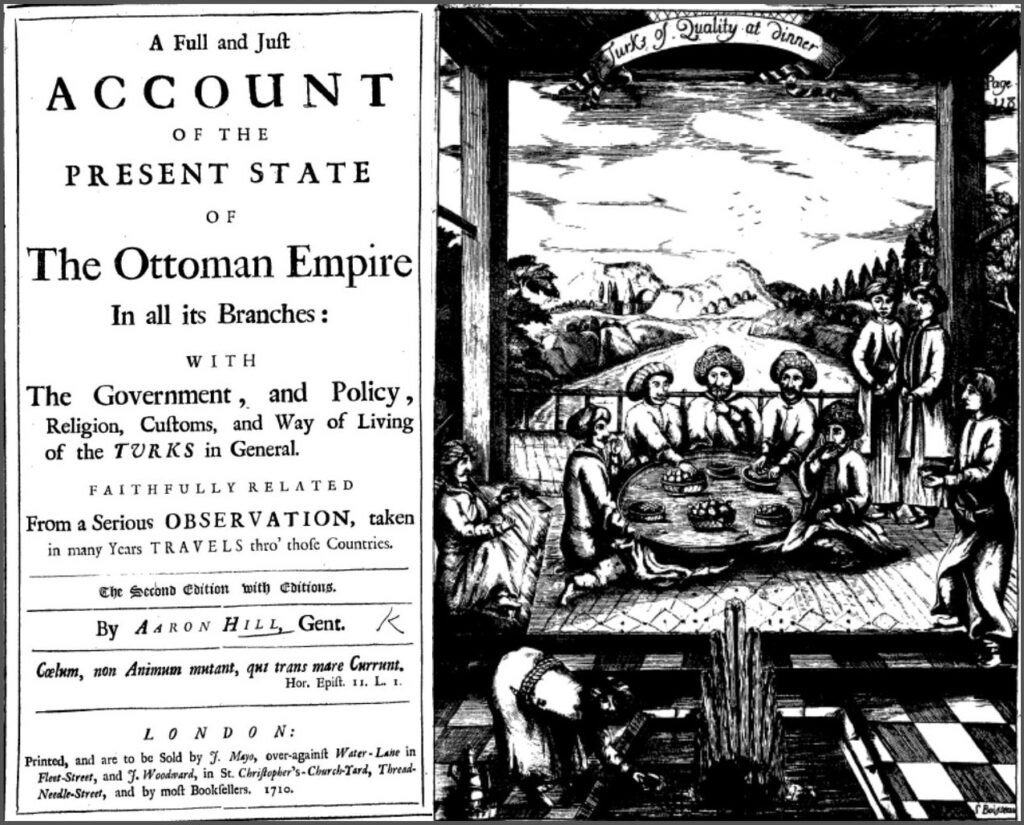

Globalisation and Orientalism

When her husband, Edward Wortley Montagu, was appointed ambassador to Constantinople in 1716, Lady Mary was granted an unusual opportunity for an English woman to travel and experience other cultures. This female perspective is perhaps what makes her correspondence – several versions of which are available in ECCO – so special.

Lady Mary lambasted the stereotypes and inaccuracies disseminated by English male travellers in earlier accounts of the Middle East, writing, “’Tis a particular pleasure to me here [in the Ottoman Empire], to read the voyages to the Levant, which are generally so far from the truth…They never fail giving you an account of the women, whom, ’tis certain, they never saw”. For her part, Lady Mary approached the women she met with a great degree of respect and recognised their mutual respect for her.

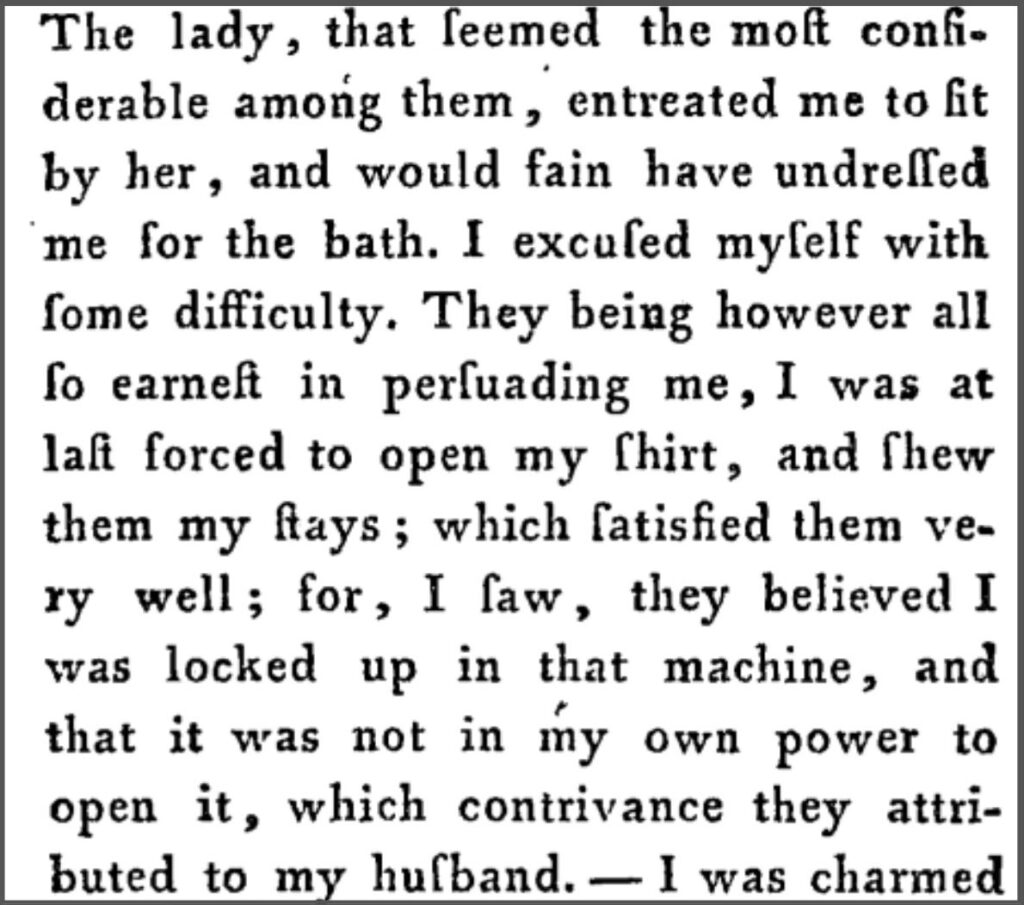

She also pointed out that, though Turkish customs were often deemed strange among the English, so were English customs among the Turkish! Describing her visit to a bathhouse, she detailed how, when the Turkish women saw the stays (corset-like garment) underneath her dress, “they believed I was locked up in that machine, that it was not in my own power to open it, which contrivance they attributed to my husband”.

In interacting with these women, Lady Mary recognised the trope, which is prevalent still today, that Islamic women were oppressed because of their faith. She thus anticipated the Orientalism that became prominent especially in the nineteenth century in Western cultures, which portrayed Muslim and Arab peoples as backward while simultaneously appropriating their art and literature.

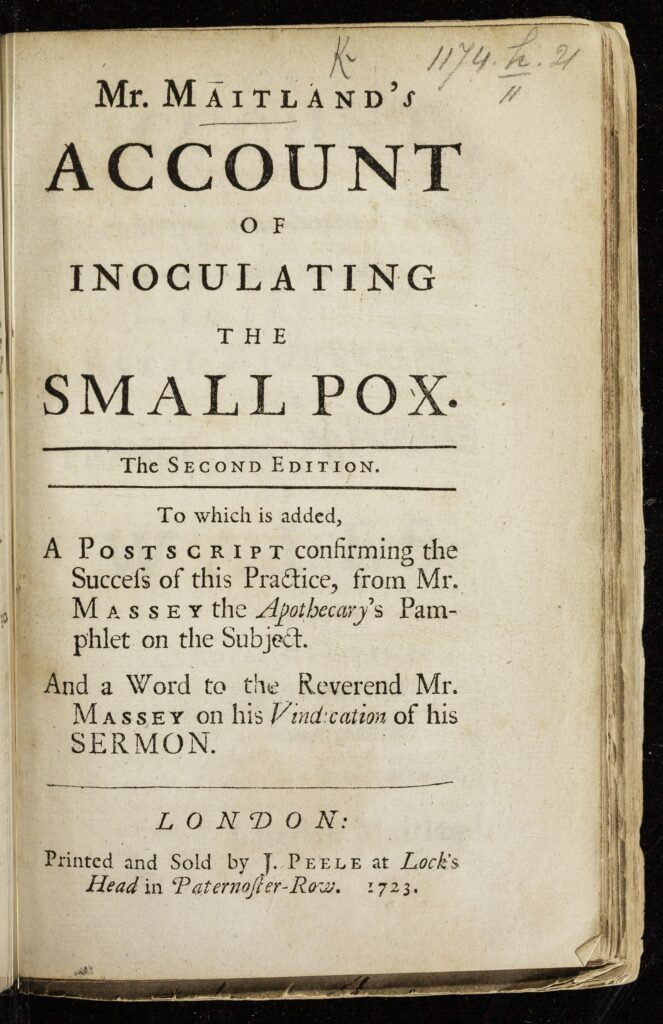

Vaccination

Lady Mary revealed her deep trust both in Turkish people as well as scientific experimentation in her descriptions of smallpox inoculation in the Ottoman Empire. In a letter dated 1717, she wrote,

“The small-pox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless, by the invention of ingrafting [inoculation]….I should not fail to write to some of our [English] doctors very particularly about it, if I knew any one of them that I thought had virtue enough to destroy such a considerable branch of their revenue for the good of mankind”.

Here, Lady Mary not only implies that Turkish medicine had superseded that of England in this way but also recognises a tendency within her home country towards profit over healthcare.

Political Theory

Along with science and travel, Lady Mary was also at the forefront of eighteenth-century political debates. In true Enlightenment fashion, Lady Mary expressed her thoughts on the influence of religion in politics. She explicitly praised Deism – the theory that God is discernible through empirical study rather than through divine revelations or religious authorities – which had influenced the likes of Voltaire and John Locke. Writing about the Effendis, or the learned men, of the Ottoman Empire, she commended them for displaying “no more Faith in the Inspiration of Mahomet, than in the Infallibility of the Pope. They make a frank Profession of Deism among themselves…and never speak of their Law but as of a politick Institution”.

She also ruminated on the theories of human nature and political institutions that characterized Enlightenment political theory, specifically social contract theory. Popularised by thinkers such as Locke, Thomas Hobbes, and Jean Jacques Rousseau, social contract theory attempted to find explanations for the formation of political society from a pre-civilised “state of nature”. For example, thinking on the conflict between the Holy Roman and Ottoman empires in the previous century, Lady Mary considered that Thomas Hobbes might have been correct in writing that “that state of nature is a state of war”.

She clearly did not champion a Leviathan monarch, though. Several of her letters warn of the dangers of autocratic and militaristic rule.

Industrialisation

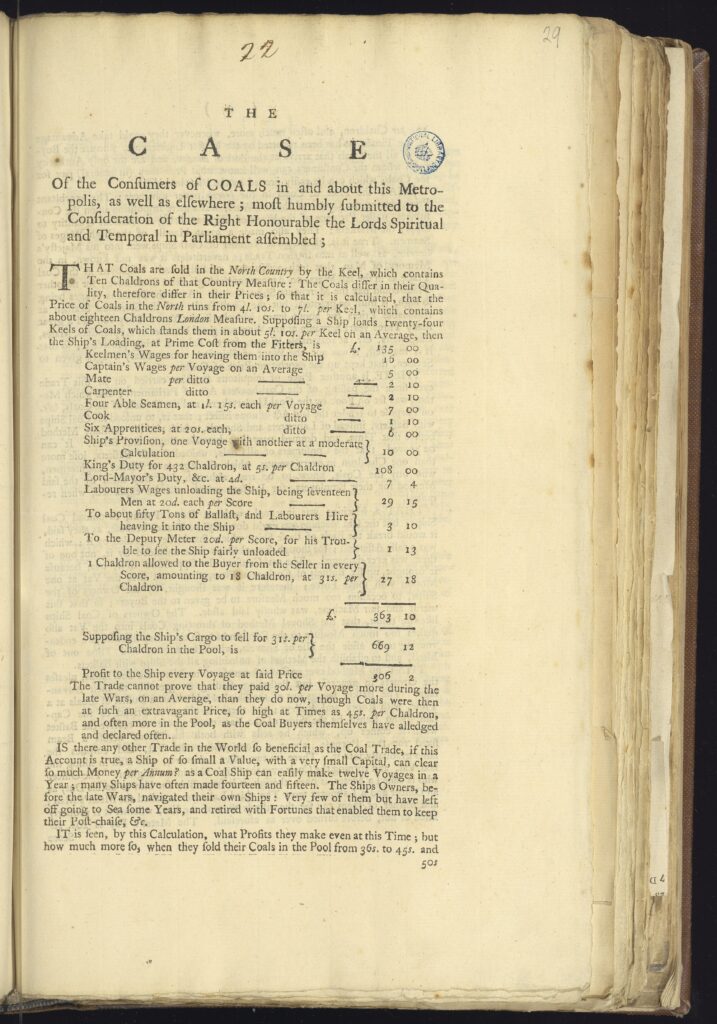

Although she was surprisingly open-minded, it is important to recognise that Lady Mary also reflected some of the less palatable phenomena of the eighteenth century. Lady Mary’s status clearly arose from the English class system in which one was born into wealth and power. But her wealth was also influenced by emerging trends in industrialisation. Her husband, for example, along with other coal-owning families, formed the Grand Allies and monopolised the English coal trade.

Conclusion

So, was Lady Mary Wortley Montagu really “ahead of her time”? I would argue that she was of her time. It is important to realize that, even while many supported the enslavement of Africans and colonialism in the Caribbean, there were those who were willing to challenge the stereotypes associated with non-Western cultures. And, while today we joke about the uncleanliness of people in the eighteenth century and their questionable medical practices (like leeches!), we would not have vaccines today if not for figures like Lady Mary.

ECCO provides more than 180,000 titles covering science and technology, literature, politics, travel, etc. with more to come. It is this range of materials that allows for well-rounded and perhaps surprising discoveries about this century and the people who lived within it.

If you enjoyed reading about Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, check out these posts:

- https://review.gale.com/2025/01/21/seventeenth-and-eighteenth-century-burney-newspapers/

- https://review.gale.com/2024/08/06/who-was-the-chevalier-de-saint-georges/

- https://review.gale.com/2024/01/23/exploring-the-inspiration-for-romanticism/

Blog post cover image citation:

Jean-Étienne Liotard. Lady Montagu in Turkish Dress. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Liotard_Lady_Montagu.jpg