│By Megan Harlow, Gale Ambassador at Durham University│

Death remains one of the few universal human experiences. After all, as mortal beings, we are all bound to face it. Yet, in today’s British landscape, death and dying have become private, taboo topics—seldom discussed until society and/or the individual is confronted in the wake of loss. For many, encounters with death prove transformative, requiring a renegotiation of identity and an exploration of grief’s emotional complexities. The role of ritual in death and bereavement becomes significant.

Britain presents a unique history of death rites. From the emergence of cremation to its domination in funerary practice, and more recently, the impact of COVID-19 on the shifting nature of death-styles, the nation’s relationship with ritual continues to evolve. Drawing on Gale Primary Sources, this article provides a glimpse into how death rites adapt to affirm identity, foster memory, and bring life to the face of mortality, highlighting the ever-evolving relationship between societal change, grief, ritual, and identity in British funerary practices.

The Emergence of Cremation: A Cultural Ritual Shift

Today, approximately 80 percent of Britons choose cremation as their preferred method of corpse care.1 However, this has not always been the case.

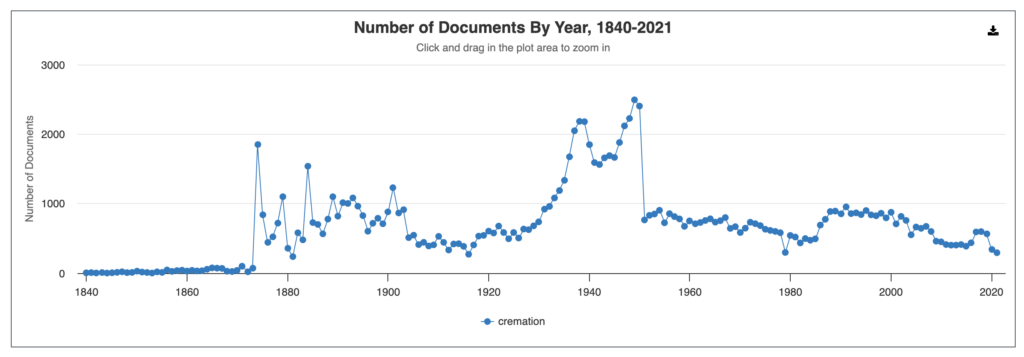

Illustrating a gradual process, a term frequency search traces its emergence to the late nineteenth century, when concerns over public welfare and overcrowded cemeteries, alongside shifting attitudes, began to challenge traditional burial practices.

The establishment of the Cremation Society of Great Britain in 1874 marked an early effort to promote new ritual practice. However, it remained highly contentious and largely did not enter the public domain until 1884.

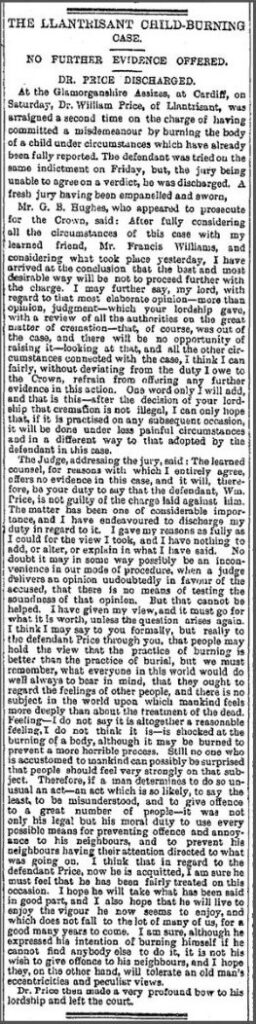

One can attribute the turning point to Dr. William Price. A radical Welsh physician, Price attempted to cremate his deceased infant son on an open-air pyre atop a hill in Llantrisant. Price’s act incited widespread indignation and ultimately led to his arrest. Primary sources detail his trial, and how his eventual acquittal established a crucial legal foundation for cremation in Britain, provided it caused no public nuisance.

This case, where personal interest in Druidic rituals, grief, and the need for remembrance converged, underscored cremation as a response to shifting cultural belief. Catalysing the efforts of the Cremation Society, Price effectively resolved a long-standing impasse with the Home Office, paving the way for Britain’s first official cremation in 1885 and the passage of the Cremation Act in 1902.

Ritual Paradox: The Death of Diana

From the death of a relatively obscure figure with a profound impact to the passing of a globally renowned figure, ritual practices have evolved in response to cultural trauma.

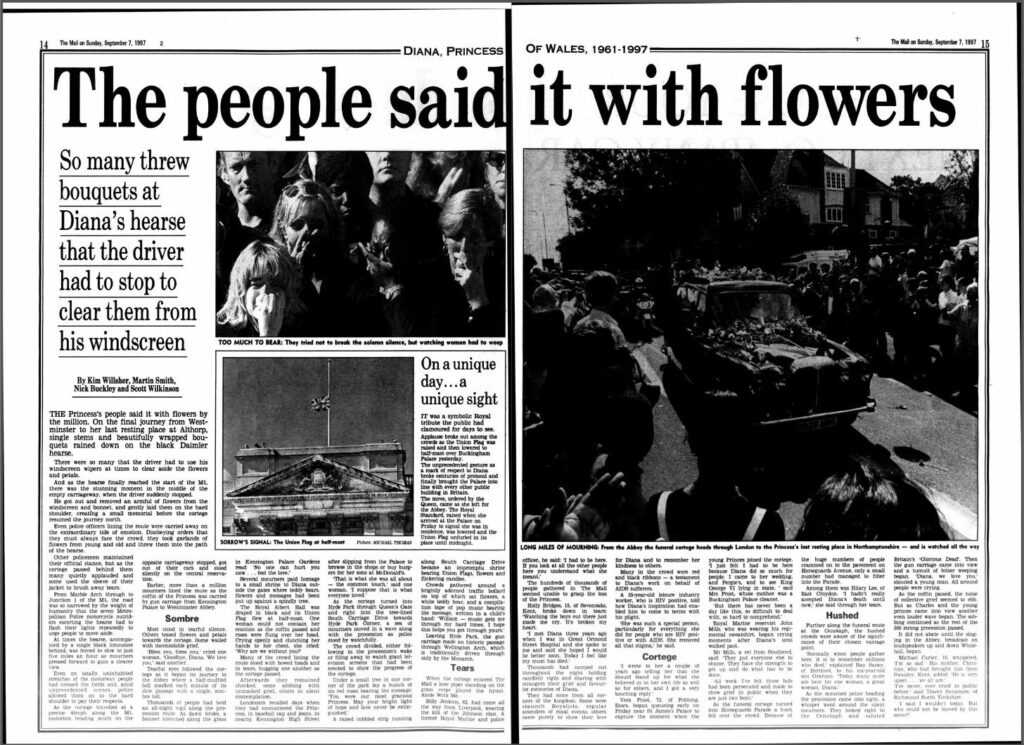

It is said that crowds offered “flowers by the million” in response to Diana, Princess of Wales’ death in 1997. A memorial for a woman many had never met but felt deeply connected to, the scale of the floral tributes and the profound experience of collective mourning transcended typical British boundaries of grief and transformed the social fabric of London, if not the world. Kensington Palace Gardens were the host of society—a striking display of dividual personhood, as mourners carried their personal grief into a shared public ritual.

Commentaries on the events are richly documented in the pages of British newspapers, with the Mail on Sunday dedicating pages to the coverage of her funeral, and journalist Paul Johnson calling the mourning “a spontaneous collective religious act by the nation”, not merely a ceremonial farewell but a cultural watershed moment. The articles demonstrate how the British people, through the sea of flowers, embodied a profound paradox—life within death—and redefined grief as a form of social engagement.

Flowers thus became ritualistic, transforming mourning, and fostering remembrance and expression worldwide—a phenomena mirrored once again within COVID-19.

COVID-19: Shifting Death Styles

This article has been written largely in the aftermath of COVID-19. One cannot ignore how the virus irrevocably transformed how societies confront death, grief, and remembrance. With rising numbers of dead, funeral homes and the bereaved faced challenges as public health restrictions reshaped every aspect of death and mourning. Primary sources from across the globe indicate the impact of the death toll on crematoria, staff, and ritual practice.

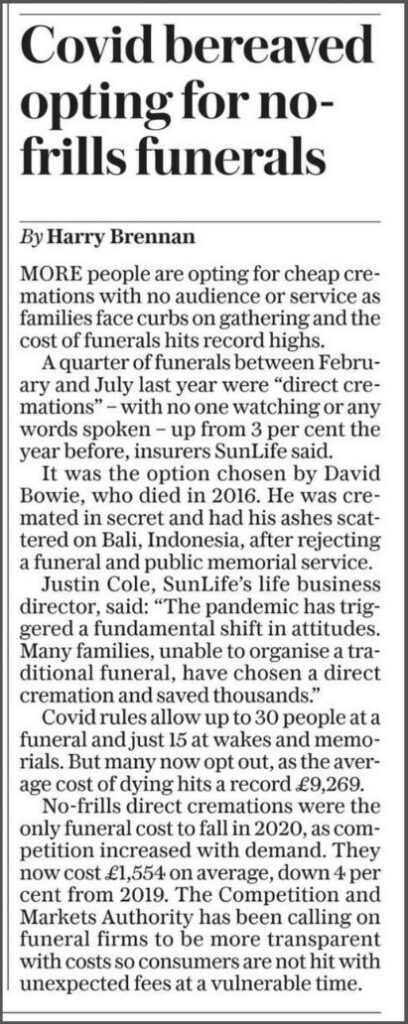

One of the immediate impacts of COVID was the rise of direct cremation—cremation without the ritualised, formal ceremony. Once a niche choice, such practice became a necessity imposed by lockdown, accounting for some 25 percent of funerals during the first UK national lockdown. However, despite some positive reception, the loss of ritual accompanying these funerals raises significant concerns about their long-term impacts, particularly in navigating mourning and sustaining meaningful bonds with the deceased.

As formal rituals declined, new forms emerged. The National COVID Memorial Wall, adorned with thousands of hand-painted red hearts, became a striking symbol of remembrance. Built through the community engagement, the ‘Hearts Wall’ allowed the bereaved to inscribe personal messages. Accounts from mourners describe feelings of connection, finding solace in knowing their grief was not isolated but part of a national tapestry of loss. The creation of such a memorial highlights the adaptability of ritual to sustain identity, both personal and collective, even in the crisis of unprecedented loss.

Personalising Death: Evolving Rites

Funerary rites have never been static, today’s deathscape is as diverse as life itself. While religious services are still, and will likely continue to be popular, cultural shifts have reshaped funeral norms, fostering the ever-increasing personalisation of death.

Ecological concerns, for example, have spurred the rise towards natural burials, where bodies are returned to the earth with biodegradable materials. Emerging in the 1990s, these sites plant trees as living memorials, turning the landscape itself into a place of remembrance.

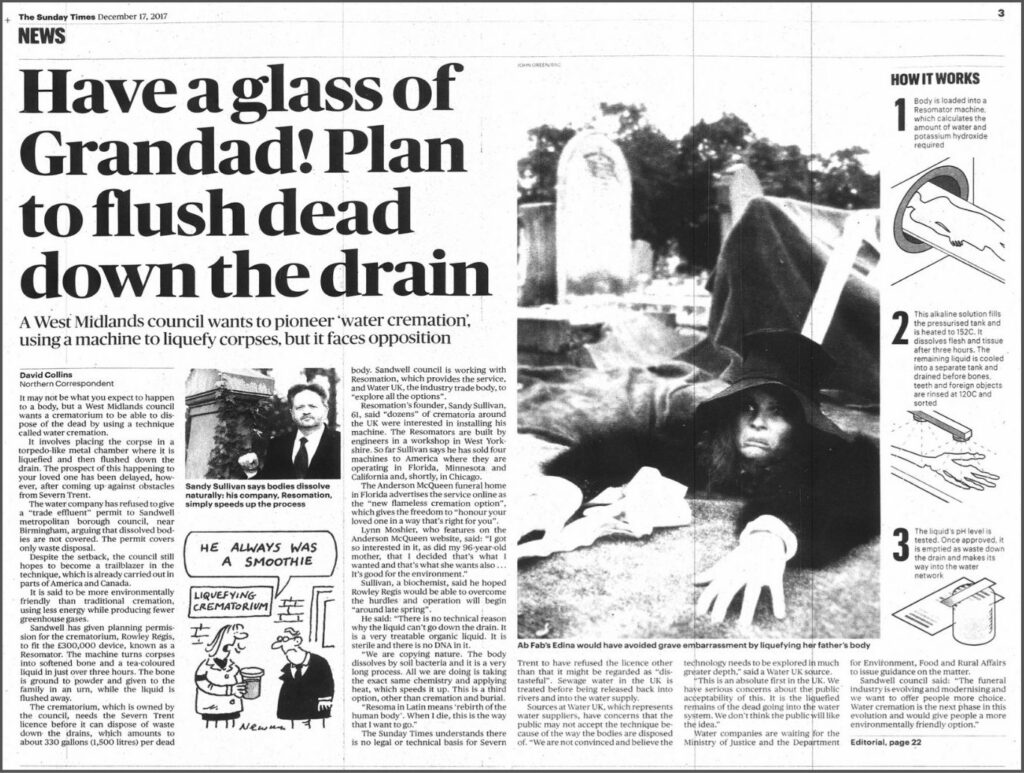

Advancement in science has introduced alkaline hydrolysis, or water cremation. A process which uses heat, pressure, and chemicals to break down the body, mourners are left with a familiar type of ‘cremains’. Touted as an environmentally friendly alternative, it has gained traction in British media for its gentler, baptismal approach to body disposal, though it has also been subject to sensational headlines.

Conclusion

As Britain embraces these ‘new’ rituals of corpse care, the language of death is constantly evolving. In examining these sources, we gain a deeper understanding of how rituals reflect identity, illuminating the rich tapestry of practices that have shaped and will continue to shape the ways in which we mourn and remember, and ultimately find enduring connection in the face of life’s inevitable end.

With special thanks to Douglas Davies, whose expertise and insights provided invaluable inspiration for the ideas explored in this article.

If you’re interested in exploring themes of death, identity, and the role of primary sources in historical study, check out these posts:

- Exploring Community and Identity in Sexuality and Gender History – Archives of Sexuality and Gender: Community and Identity in North America

- The Death of George V – As Reported First in The Times

- The Influence of British Media on its Politics: Insights from Gale Primary Sources

Cover Image: Maxwell Hamilton, Flowers for Princess Diana’s Funeral, 1997 https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Flowers_for_Princess_Diana%27s_Funeral.jpg&oldid=896339556 [accessed 29 January 2025].