│By Leila Marhamati, Associate Editor, Gale Primary Sources│

Post-colonialist thinker Frantz Fanon declared the importance of language in a world globalised through empire and colonisation: “To speak… means above all to assume a culture, to support the weight of a civilization”. It is ironic to cite this quotation in translation from the original French, as Fanon’s point is that the language we speak is both a product of and perpetuates the culture we live in. As an English speaker, what do I know about his thinking? His worldview?

For societies and nations founded through colonialism, language is crucial. The language of the coloniser is often forced upon the colonised. Holding onto a language despite imperialist pressures then becomes a form of resistance and a declaration of selfhood. All of these implications of language can be explored in Gale Primary Sources’ Archives of Latin American and Caribbean History, Sixteenth to Twentieth Centuries.

King and Country

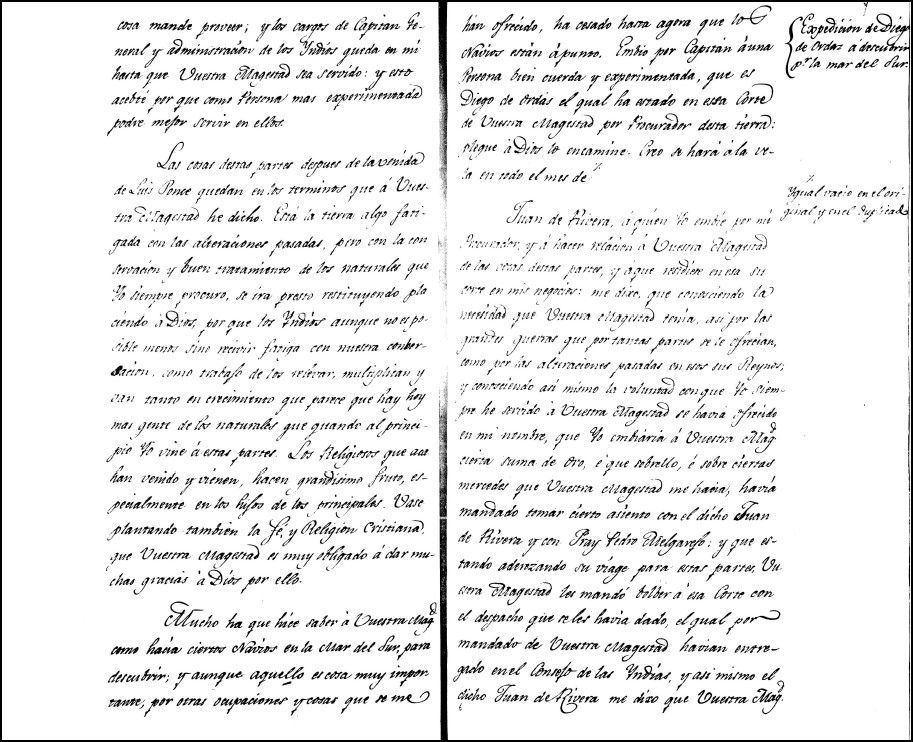

Archives of Latin American and Caribbean History is a multilingual archive, containing documents written in English, Spanish, French, Portuguese, and other languages. The collection titled “Conquistadors: The Struggle for Power in Latin America, 1492-1825” has several documents written in Spanish. The importance of digitising these manuscripts in their original language is made apparent by exploring letters written by Hernάn Cortés, the “conqueror” of Mexico.

Besides illustrating some lexicographic changes in the Spanish language, these letters provide essential insights into the worldview Cortés brought with him to Latin America. Cortés consistently addresses his writing to “Vuestra Cesarean Magestad”, assuring that every action he takes is done in the name of the emperor, Charles V. The inclusion of “Cesarean” directly links Charles V to Julius Caesar. This is different from how his title is usually written in English – Holy Roman Emperor – as the latter does not necessarily evoke the person of Caesar himself. In referring to the emperor as Caesarean, Cortés’ language evokes connotations of masculinity and personality that “Holy Roman Emperor” does not.

It almost doesn’t bear mentioning that, of course, the Roman empire and Caesar were of no historical importance to the indigenous peoples of Latin America at this point. But the imposition of Spanish rule and its language also imposed this history onto them.

Spread the Faith

These letters also reveal how Cortés draws attention away from the power he exerts in Mexico over the indigenous peoples through his language of extreme deference to higher powers. Cortés promises Charles V, “above all things in the world I have desired to make known to Your Majesty my fidelity and obedience” (these are my own translations). It becomes clear in his writing that his “fidelity” is used to justify his treatment of native peoples.

Cortés describes how, though the land was “fatigued” following European arrival (an interesting way to say that the indigenous population was decimated by warfare), his procurement of “good” treatment for the natives contributed to their numbers “multiplying”. His use of this word seems to refer to the Biblical phrase “go forth and multiply”. The European cultures of Christianity and monarchy thus seeped into the language the colonisers used that they then enforced upon the indigenous peoples. Religious language couched the devastation they clearly brought to the land and people.

Native Languages in Colonial Latin America

In the early stages of colonisation, European explorers like Domingo de Santo Tomás understood that learning the native languages of Latin America would be helpful, compiling books on native vocabulary and grammar. This interest in the language did not last, as the nearly 500 million native Spanish speakers today prove. Indigenous communities have struggled to maintain their languages in the face of racism and discrimination. But many still do exist, in some way keeping the culture and history of pre-Colombian Latin America alive.

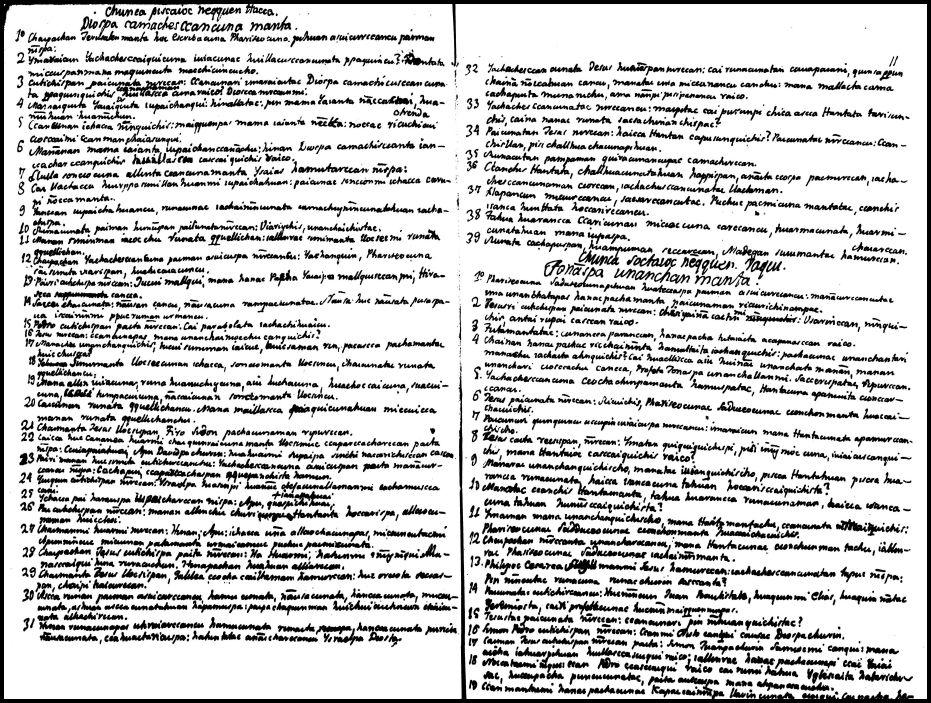

A manuscript document of the Christian gospels written in Quechua – the official language of the Incan Empire – can give us insights into how this language survived despite colonial pressures (it’s spoken by about 7 million people today). The document is undated and anonymous; we can’t know if a European missionary wrote it to encourage conversion or if a bilingual native created it to bridge cultures. However, just its mere existence is noteworthy.

Fanon said that speaking a language allows someone to adopt a certain cultural worldview. Even though this document is Christian in doctrine, the fact that it’s written in Quechua means that the reader combines his or her indigenous worldview with the text, making it in some way their own. As long as this document exists, then, so can Incan culture. It also, of course, helps the survival of the language by writing it down (Quechua did not have a written system).

So despite colonisation and discrimination, this document shows how indigenous peoples could maintain their pre-Colombian cultures. This even reflects the cultural practices in Latin America today that combine ancient traditions with colonial ones – Día de los Muertos celebrations, for example, fuse pre-Colombian rituals with the Christian tradition of All Souls’ Day.

Conclusion

The examples I’ve provided come from only one collection in this vast archive. The possibilities of exploring language and all of its social and political implications extend much farther – how can you not think about these implications while reading the letters of the Great Liberator Simón Bolívar, written in Spanish yet opposing Spanish rule? Or in considering the impact of the Cry of Dolores on the Mexican War of Independence? Or in studying twentieth century protest literature?

Language does more than allow people to communicate – it gives us a way to process our experiences and build our knowledge and views of the world. The significance of a multilingual archive in studies of history cannot be understated.

If you enjoyed reading this blog post, then check out these:

- United Farm Workers and Chicano Literature: Primary Sources as a Tool for Language and Cultural Studies

- Emancipating a Continent: Studying the Americas Through The Region’s Liberators

- Peyote Rights, Religious Freedom and Indigenous Persecution in the Women’s Missionary Advocate Papers

Blog post cover image citation:

Abbott, John Stevens Cabot. History of Hernando Cortez. Harper & brothers, 1855. Archives of Latin American and Caribbean History, Sixteenth to Twentieth Century, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CY0101109019/LACH?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-LACH&xid=bf0b8d15&pg=240.