│By Ray Linn, Gale Ambassador at Maynooth University│

I started studying Spanish nearly 8 years ago now, but it never interested me so much as last year, in the final year of my undergrad degree, when I enrolled in a Chicano/a Literature module. I hadn’t studied literature much previously, but in that class, I learned how essential it is to living. It allows us to connect with people whose experiences are different from our own, and to see the world through lenses that were previously unknown. But reading requires context. Using primary sources allows me to contextualize what I read when it comes from cultures and histories I’m unfamiliar with, allowing my view to expand and my understanding to grow.

Chicano Literature: …y no se lo tragó la tierra

One of the first books I read in that pivotal literature course was …y no se lo tragó la tierra by Tomás Rivera, one of the first books on Chicano experience to be published in the US in Spanish back in 1971. It follows the inner monologue and experiences of a young boy from a migrant worker community. It’s not a long book, but it is very heavy, filtering traumatic encounters of violence and racism through the gaze of a frightened child. It is incredibly impactful and offers insight to its setting alongside powerful critique of the culture at the time.

A constant and heartbreaking thread throughout the book is unfair treatment of the Chicano protagonist and his family at the hands of the farm owners they work for. The whole family, children included, perform heavy labour in dangerous conditions. They are poorly paid, denied their basic needs, and housed in precarious dwellings. Though the book is fictional, this experience was common during the time it was written.

Knowing the historical significance of what we read allows us to understand it, but also the world around us, in a much deeper way. Looking for further information, I fell down a rabbit hole, and ended up learning about Chicano labour action, which is a major building block to understanding the Chicano Civil Rights movement, and Chicano history in general.

Chicano Struggle: United Farm Workers

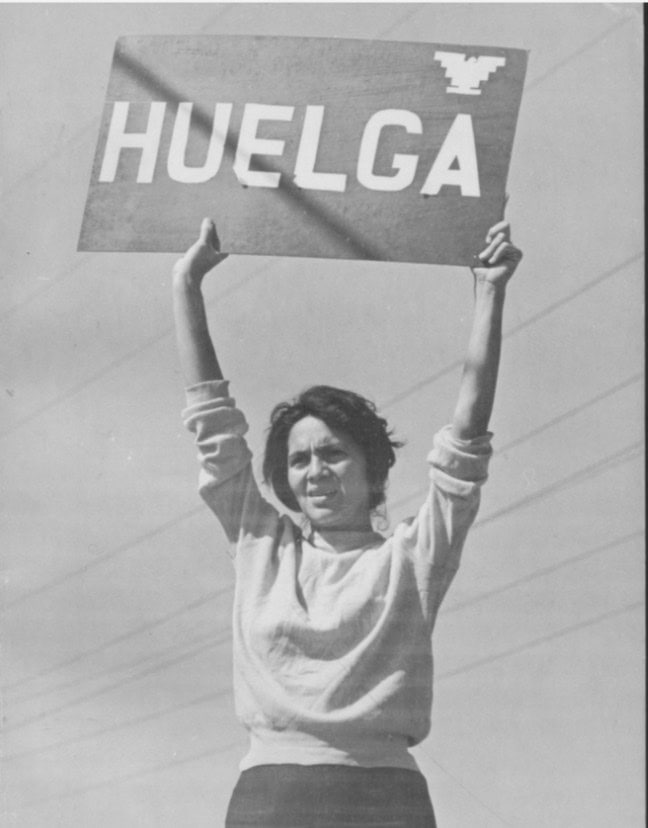

Just like in Rivera’s novel, for much of the twentieth century, migrant farm workers were subjected to deadly conditions, and because many were not white, their plight was outright ignored by the white-majority labour unions of the day. The formation of United Farm Workers (UFW), a joint effort between two workers’ rights unions, aimed to change these conditions, and was pivotal to changing lives and furthering racial equality. Their insignia was the Aztec eagle, a symbol of identity still used by Chicanos today, representative of the fact that Chicanos were standing up for themselves, not allowing exclusion to stop them.

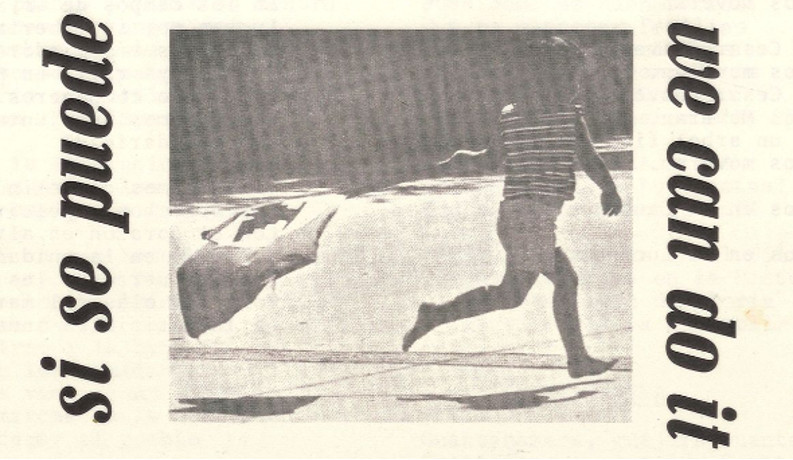

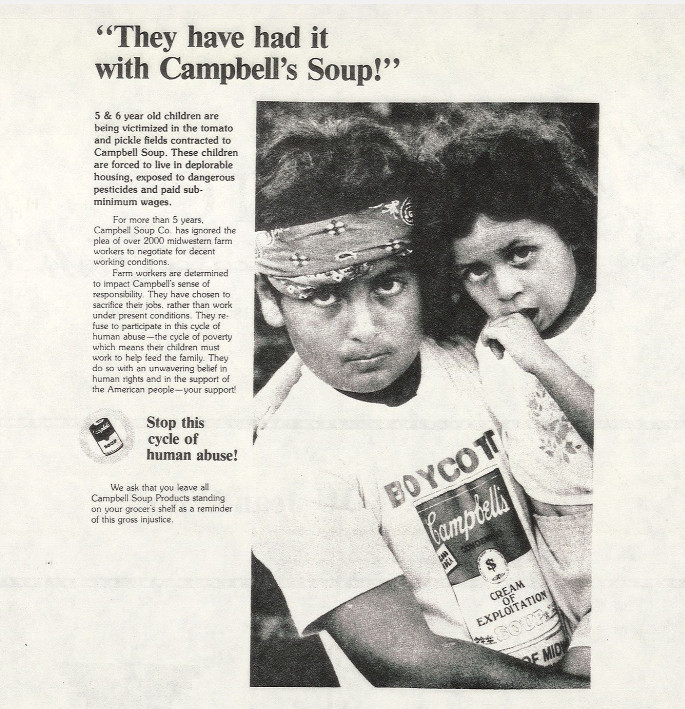

The reality of the migrant worker at the time was grim. This source from Archives Unbound is a collection of UFW documents from 1972 to 1985, including pages and pages of demands, in English and Spanish, speaking out against farm owners taking advantage of workers, including paying below the minimum wage, stealing social security from the elderly, and union-busting when workers asked for fairer treatment. Some also call out the US government for unfair treatment of strikers, and for deporting workers back to unsafe places.

UFW’s journey was not easy, and often met with resistance from farm owners and law enforcement alike. Though the entire country enjoyed Mexican labour, those in power did not want to listen to or respect the human rights of the people who made up that labour force.

In 1965, the historic Delano Grape Strike began, headed by the United Farm Workers and their leaders, Chicanos Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. Huelga, a monograph in Archives Unbound, acts as a firsthand account of the first 100 days of this almost 5-year strike over 150 pages. It brings to life the struggle by telling the ins and outs of what each day was like and run-ins with farm-owners and workers.

Huelga is a history book, but also a firsthand account of the experience of facing up against police, farm owners, and the US government. It recounts the solidarity felt by the workers, as well as the opposition and violence they faced while petitioning for human rights. In the end, UFW came out victorious in the Strike after years of consistent and continued organization and struggle.

Modern Impact: Understanding

UFW’s activism brought about better pay and conditions, but it also created a campaign of raised awareness of injustice, leaving a tangible, recorded history of a group of people whose story would otherwise go untold. The records of their strikes and demands have allowed me to gain a more intimate understanding of the history behind important pieces of literature, as well as an understanding of the Chicano Civil Rights movement itself.

Why do we study languages? Everyone starts in Spanish 101 with different motivations. Underscoring each motivation, however, there is one thing that ties them all together: the language learner seeks to understand other people.

How do we understand people without understanding their history? How do we read stories from experiences foreign to our own, without taking the time to understand how and why they are? Understanding UFW’s triumphs helps us to understand the place where some Chicano literature comes from, but also helps us to understand where we are today and how far is left to go. UFW is still active, still fighting against continued injustice. Likewise, the tradition of Chicano literature continues, standing as always in front of a background of struggle and triumph.

If you enjoyed reading about Chicano labour action, check out these posts:

- Global Communist and Socialist Movements – The Third Instalment of Political Extremism and Radicalism

- Decolonization: Politics and Independence in Former Colonial and Commonwealth Territories

- Birth Control: A History in Women’s Voices

Cover image: UFW Arizona, 1972-1985. 1972 – 1985. MS National Farm Worker Ministry: Mobilizing Support for Migrant Workers, 1939-1985. Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University. Archives Unbound. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/SC5109833425/GDSC?u=webdemo&sid=bookmark-GDSC&xid=364c68f0&pg=21