│By Meg Ison, Gale Ambassador at the University of Portsmouth│

During my undergraduate studies, I read History and French. When I began looking for research funding for a PhD, I realised that so much research in the academy at the moment is interdisciplinary. Indeed, it has become somewhat of a ‘buzzword’. I combined research methods from the Humanities and Social Sciences in my research proposal to win a place with the South Coast Doctoral Training Partnership, funded by the Economic and Social Science Research Council. I completed their MSc in Social Research methods at the University of Southampton, and now I am on the interdisciplinary pathway for my PhD. I did not fully appreciate the potential and importance of interdisciplinarity until I started studying for my PhD with a cross-departmental supervisory team. As a result, I have a strong interest and belief in the power of interdisciplinary study. In this blog post I share some of my insights about this approach to research.

Part One: The History of Interdisciplinarity and its Challenges

Anthroposophical medicine, according to this article published in The Times in 1998, was an approach developed by Austrian scientist and philosopher Rudolf Steiner in the early twentieth century. His holistic approach to health drew on the teachings of many different disciplines within the Arts, Humanities, Sciences, and Social Sciences. He intended practitioners to use his approach for the treatment of a wide range of diseases, from anxiety and depression to hay fever and asthma.

Steiner’s interdisciplinary approach to research can be considered ahead of its time. Indeed, academic disciplines tended to be very traditional at this time in history. It is only really during the past thirty years there has been a marked shift towards interdisciplinary research in Higher Education institutions in the United States and the United Kingdom, in response to the neo-liberal commodification of culture and the global crisis of the Humanities.1

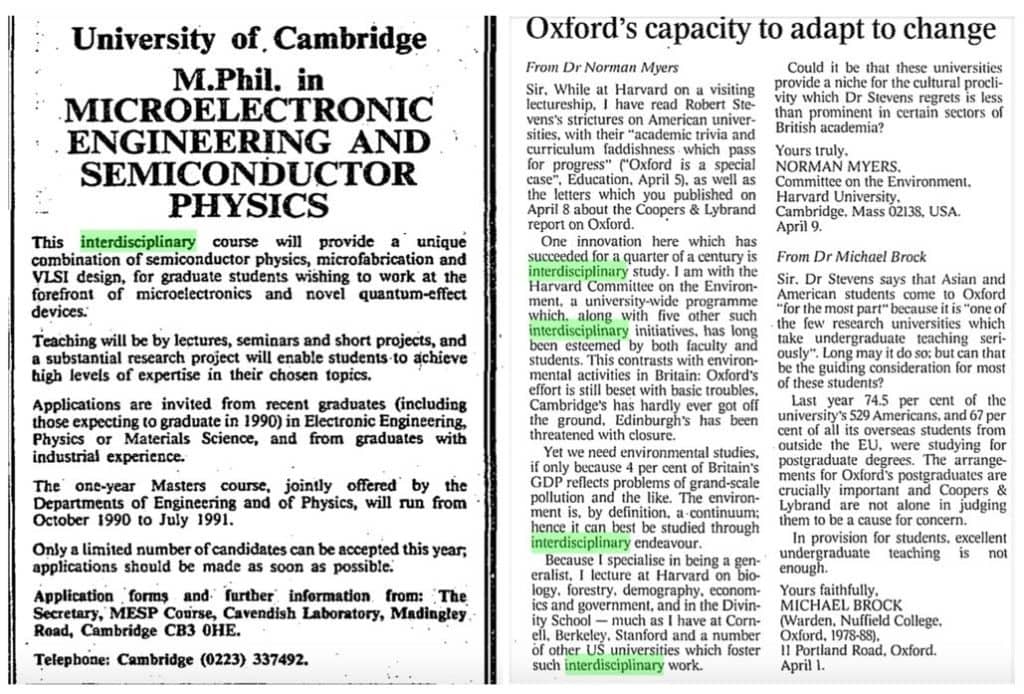

Left: “University of Cambridge.” Times, 19 Mar. 1990, p. 30. The Times Digital Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IF0500285812/GDCS?u=uniportsmouth&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=8291aa8d

Right: Myers, Norman, and Michael Brock. “Oxford capacity to adapt to change.” Times, 15 Apr. 1996, p. 19. The Times Digital Archive, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IF0501163643/GDCS?u=uniportsmouth&sid=bookmark-GDCS&xid=0081ac57

For those of you reading this blog post who are academic researchers, you may already be aware that there is a new canon of literature that justifies this ‘interdisciplinary turn’ in the Humanities and Social Sciences in its broadest sense. For example, Myra Strober, a labour economist and Emerita Professor of Education and Economics at Stanford University, argues that there are two major premises underlying the push for interdisciplinarity: that ‘the solutions to some problems requires insight from multiple disciplines’, and ‘the diversity of disciplinary knowledge, perspectives and methods is a source of creativity’. 2

Nonetheless, Strober’s former colleague, Diana Rhoten, identifies two major barriers to its success in the UK Higher Education system. The first is that ‘scholars are not necessarily willing to work across disciplinary borders’, and the second is ‘the university sector’s tendency to approach interdisciplinarity as a trend rather than a real transition’. 3 For example, Timothy Ingold, the Chair of Social Anthropology at the University of Aberdeen, recently warned ‘wannabe ethnographers’ to stop meddling with research methods outside of their disciplinary traditions and called for ‘a halt in the proliferation of ethnography and a return to anthropology’.4 Generally speaking, the social meaning of interdisciplinary research thus lacks clarity, because there are two contradictory calls in circulation: one is the turn towards interdisciplinarity as a key goal, the other is that to have firm roots in one single discipline is ‘desirable’. 5

You can read about my struggles in negotiating an interdisciplinary identity at the beginning of my PhD journey in my blog post for the South Coast Doctoral Training Partnership here.

Part Two: Why Interdisciplinary Research is Relevant

A holistic approach to learning

Given these difficulties and challenges, you may be left wondering what the potential and importance of interdisciplinarity is in academia! Well, there are so many advantages, and here I am going to share my three favourites with you. From my experience, I have discovered that many terms and concepts I use in my research are interdisciplinary in their own right (i.e. many different disciplines use them and give different meanings to the terms/concepts). Taking an interdisciplinary approach helps me to add depth and breadth to my analysis, by adopting a holistic approach to learning. This is because I have learnt that if I just read works in my home discipline (History) I would be shutting off whole areas of knowledge. Interdisciplinarity has taught me that ‘knowledge’ does not belong to anyone, and this has made me far more curious and adventurous in my work!

Key terms such as ‘gender’ are taken more seriously

The second reason is that interdisciplinarity has made it much more popular in the last thirty years for certain very relevant, interdisciplinary terms, such as ‘gender’ and ‘(multi-)culture,’ to be taken more seriously in academia. The importance of this liberalism cannot be overstated.

Using different literatures, methods and source types stretches researchers

The third reason is that interdisciplinarity, in my opinion, makes you a stronger researcher. Working across different disciplines often means stepping outside of your comfort zone into unfamiliar territory. This can be daunting, but it can also be so rewarding. By working within the field of Anthropology as well as History in my research, I have developed strong critical thinking and problem-solving skills. This experience has been gained by using different literatures, methods and types of sources to develop and answer my research questions, which one discipline alone could not entirely encompass. I feel much more confident now than when I wrote my first blog post on interdisciplinarity three years ago! Interdisciplinarity thus allows your research – and you – to reach its, and your, full potential, and is really important for the creation of useful, well-rounded, relevant academic knowledge.

Part Three: The Relevance of Gale Primary Sources

To end this blog post, I would like to share an anecdote with you that for me encapsulates the spirit of interdisciplinary curiosity, and highlights the role that Gale Primary Sources can play in supporting this interdisciplinary turn in academia. During an event I ran at the University of Portsmouth (before the Covid-19 pandemic) designed to inform students about Gale Primary Sources available at the library, an undergraduate medical student approached me. She asked me how she could use historical archives to write her assignment on legalised drug use (penicillin) in the community, and together we found that Gale Primary Sources had a lot to offer in this research area!

Over a century on from Steiner, another curious medic was able to put together a fascinating science paper by drawing on methods (primary source historical document analysis) that are traditionally associated with the Humanities, especially History and English Literature.

A huge benefit that Gale offers for this type of research is that its database doesn’t have the same rigid structure for the organisation and categorisation of knowledge as the academic disciplines in Higher Education institutions. For example, rather than searching by discipline for specific information, the search functions sort information by source type, date, theme, name and place, amongst other things, which allows for far greater creativity and fluidity in research. This blog post has aimed to show that the potential and importance of interdisciplinary research is enormous, and has highlighted how Gale Primary Sources is a great resource to use if you would like to try this approach out in your own research. For an example of how to use Gale Primary Sources for interdisciplinary research, check out this blog post by a fellow Gale Ambassador on The Gale Review on Environmental History and ethnobotanical research!

If you enjoyed reading about interdisciplinarity and the value of digital archives, you might like:

- Why Use Primary Sources?

- Moving from Undergraduate to Postgraduate Study: Using Digital Archives More Proficiently

- How Gale Digital Scholar Lab Could Support Alternative Research Methods

- Free Speech in a “Post-Truth” Era – the Value of Digital Archives

- How To Handle Primary Source Archives – University Lecturer’s Top Tips

- How Gale Primary Sources Helped Me with My Dissertation – and Can Help You Too!

Blog post cover image citation: A design created combining an image of books by Kimberly Farmer (@kimberlyfarmer), available on Unsplash.com with an image of connecting wires by Alina Grubnyak (@alinnnaaaa), also available on Unsplash.com.

- Bérubé, M. & Nelson, C. (1995). Higher Education Under Fire. Politics, Economics, and the Crisis of the Humanities. New York: Routledge.

- Strober, M. (2010). Interdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of Thought. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p.18

- Rhoten, D (2004): ‘Interdisciplinary Research: Trend or Transition?’, Items and Issues 5, p.6

- Ingold, T. (2014). ‘That’s enough about ethnography!’, Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 4(1). p.393

- Lemercier, C. & Zalac, C. (2019). Quantitative Methods in the Humanities. An Introduction. Virginia: The University of Virginia Press.