|By Liping Yang, Publishing Manager, Digital Archive and eReference, Gale Asia|

From May 2020 to February 2021, Chinese and Indian border troops engaged in melee, face-offs, and skirmishes along the Sino-Indian border near the disputed Pangong Lake in Ladakh and the Tibet Autonomous Region, as well as near the border between Sikkim and the Tibet Autonomous Region. This series of disputes has resulted in numerous casualties, attracting worldwide attention in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such border disputes are nothing new. Three years prior to this in June 2017, the troops of the two countries had a border standoff in Doklam, a strategic location near a trijunction border area involving China, India, and Bhutan. Actually, China and India even went to war between October–November 1962 over their disputed Himalayan border.

Many of these border disputes and clashes can be attributed to the controversial McMahon Line. What is this line? And how did it come about? We can find some illuminating historical records on this in China and the Modern World: Diplomacy and Political Secrets, 1868-1950, a collection of rare historical materials selected from the India Office Records now held at the British Library.

Early Twentieth-Century Background

In the early twentieth century, especially in the years before and after the Revolution of 1911, Chinese control over Tibet had been seriously weakened due to the difficult situation the Qing Dynasty faced after the Boxer Rebellion was suppressed and a huge indemnity bill was imposed on it by the Peking Protocol signed with eight powers. At the same time, the revolutionary uprisings that culminated in the overthrow of the imperial regime in 1911 had further exacerbated the Chinese government’s position in its western frontiers. The Tibetan regime led by the thirteenth Dalai Lama expelled the Chinese resident official – Amban – and his escorts and troops, and declared the region independent in early 1913. The newly founded Republic of China and President Yuan Shih-kai were anxious to restore the Chinese administration of Tibet, leading to a series of clashes with Tibet.

The Involvement of Western Powers

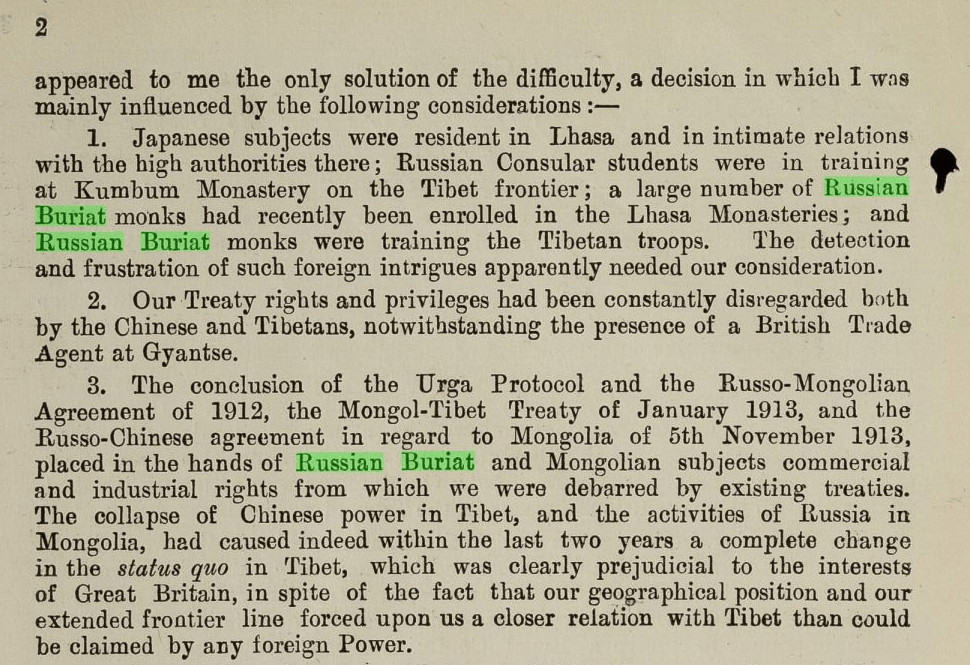

Western powers, especially Great Britain and Russia, and even Japan, showed keen interest in Tibet and Xinjiang due to their strategic location as part of the broadly defined Central Asia. To some extent, Central Asia is where the British and Russian empires met and competed against each other to expand their spheres of influence. So, in the context of this so-called “Great Game,” it was no surprise that the British colonial government in India was constantly worried about the security of its north-eastern frontiers with Tibet, which, in their eyes, might fall into the hands of Russia if they did not do anything. The Russo-Mongolia Agreement signed in November 1912 and the subsequent Mongolia-Tibet Convention concluded in January 1913, as well as reports of Russian consular students, monks, and businessmen in Tibet were all signs that Russia was trying to get the upper hand there. To counteract the increasing influence of Russia in Tibet, the British government decided to play a more proactive role in its dealings with Tibet with a view to turning it into a buffer against both Russia and China. The political chaos in Tibet and the latter’s tensions with China in early 1913 offered them a rare opportunity to act as a diplomatic mediator.

Part 3 Tibet: Negotiations with China (1913). 1913. MS Political and Secret Department Records: Series 10: Departmental Papers: Political and Secret Separate (or Subject) Files (1902-1931) IOR/L/PS/10/342. British Library. China and the Modern World, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MUTOKA902051430/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=ea681466&pg=31

The Tripartite Conference at Simla

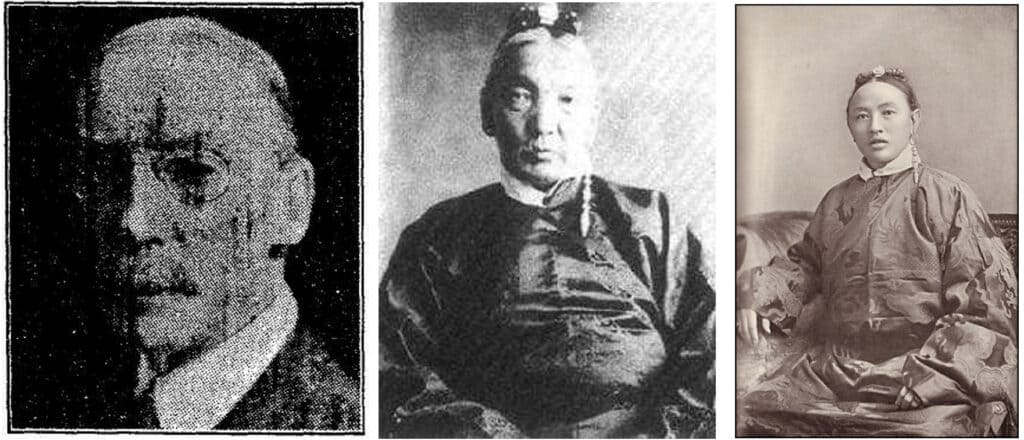

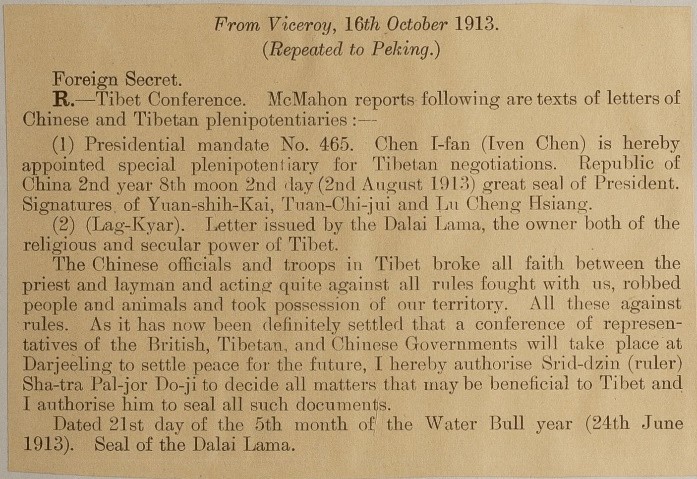

British India sent out invitations to the governments of the Republic of China and Tibet in May 1913 to participate in a tripartite conference on the question of Tibet at Simla, the summer capital of India during the colonial period. The representatives appointed by British India, the Republic of China, and Tibet for the conference were Sir Henry McMahon; Mr. Ivan Chen I-fan (陈贻范), a well-trained Chinese diplomat who had spent many years in the Chinese legation in Britain; and Lonchen Shatra, prime minister of Tibet.

Middle: Ivan Chen. Image available here.

Right: Lonchen Shatra. Image available here.

Sir Henry McMahon (1862–1949) was a British Indian army officer and diplomat who served as the foreign secretary of the British Indian Government from 1911 to 1914, and later as the High Commissioner in Egypt from 1915 to 1917. The document image below shows the credentials of the Chinese and Tibetan delegates.

The Conference was held on and off for nine months, from October 1913 to July 1914, during which the three parties went through a total of eight meetings. During this period, the conference also moved its venue from Simla to Delhi because of the cold winter weather.

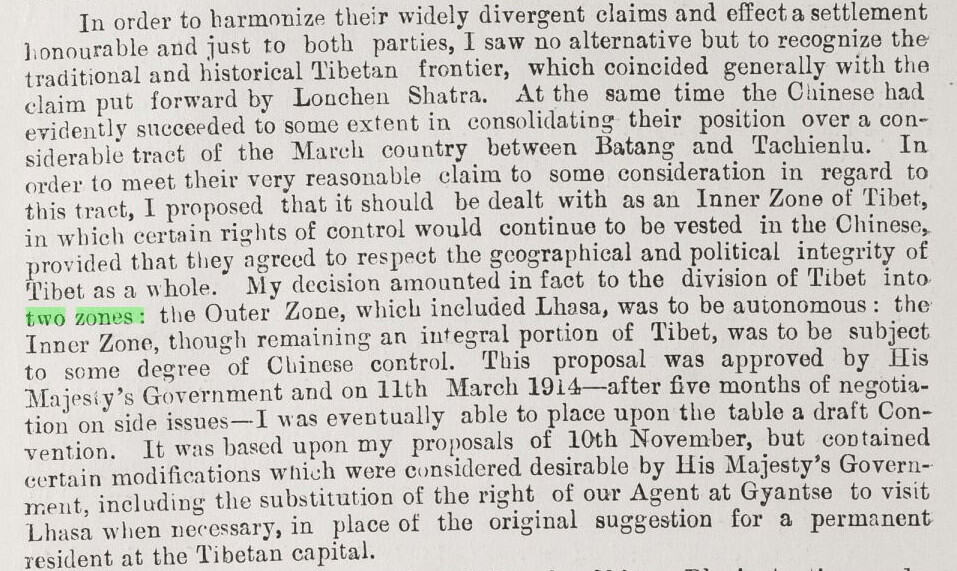

McMahon Proposes an Inner and Outer Zone

One of the key topics discussed during the Conference concerned the definition of the border of Tibet and the demarcation of the boundary between China and Tibet. Given that the submitted territorial claims of China and Tibet overlapped a lot, McMahon proposed that Tibet be divided into two zones: an Inner Zone and Outer Zone. The Outer Zone referred to Tibet proper, centered around Lhasa, which was then under the effective control of the Tibetan theocratic government, whereas the Inner Zone described a long strip of area surrounding the Outer Zone on the east and north. At the same time, it was also proposed by the British that full autonomy be granted to the Outer Zone, although a Chinese high official with a limited number of escorts would be allowed to be based in Lhasa, as a sign of Tibet under the Chinese suzerainty. For the Inner Zone, which functioned as a sort of buffer between Tibet and China, China would have rights to station her troops and administer the areas while respecting the integrity of Tibet.

Tibet: Sir H McMahon’s Report on the Tripartite Negotiations. 20 Nov 1913-20 Aug 1914. MS Political and Secret Department Records: Series 11: Departmental Papers: Political and Secret Annual Files (1912-1930) IOR/L/PS/11/80, P 2964/1914. British Library. China and the Modern World, https://ink.gale.com/apps/doc/CTEFZS618023388/CFER?u=omni&sid=bookmark-CFER&xid=d1289598&pg=19

This was far from an easy proposal as China and Tibet found it very hard to agree on the two boundary lines separating the Outer and Inner Zones, and the Inner Zone and China proper. There were a lot of discussions, including internal ones involving the viceroy of British India in Delhi, the secretary of state for India (head of the India Office) and the secretary of state for foreign affairs in London, as well as the British minister to China based in Peking, plus the discussions that happened among the Chinese delegate, the Chinese government in Peking, and the Chinese minister based in London, and those of Tibetan representative with the Lhasa government.

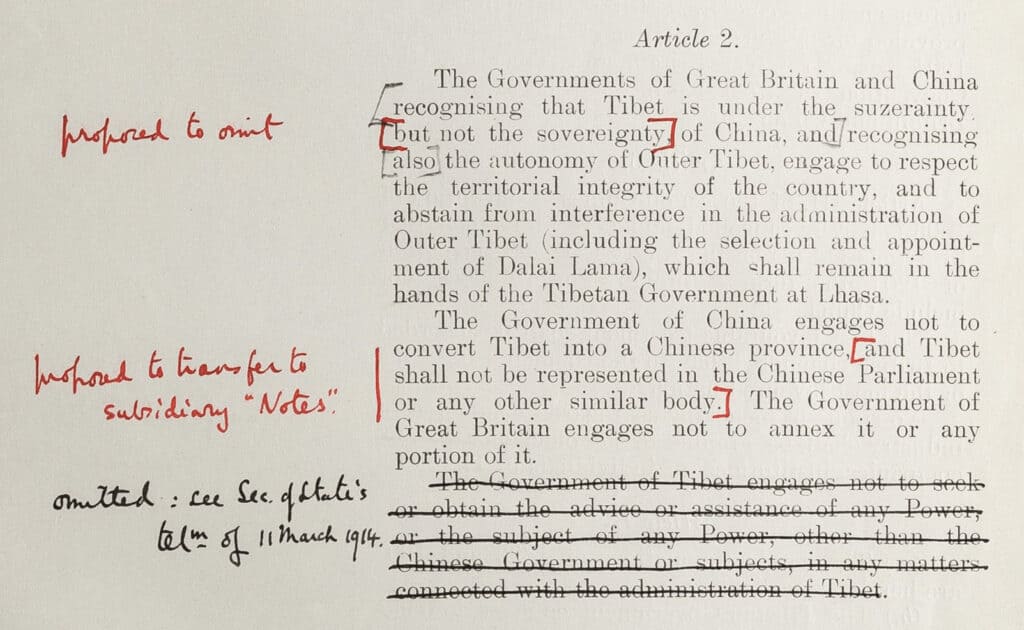

A Draft Tripartite Convention is Drawn Up

All the key topics discussed and debated at the Conference found their way into a draft tripartite convention, consisting of 11 articles. Some articles had gone through several rounds of revisions based on the feedback of China and Tibet as well as the mediating British government’s own considerations, such as her concerns about Russia’s reactions or objections based on the Anglo-Russo Convention of 1907 that barred both Britain and Russia from intervening in Tibetan affairs. Below is an example of the draft convention showing comments and suggestions for modification.

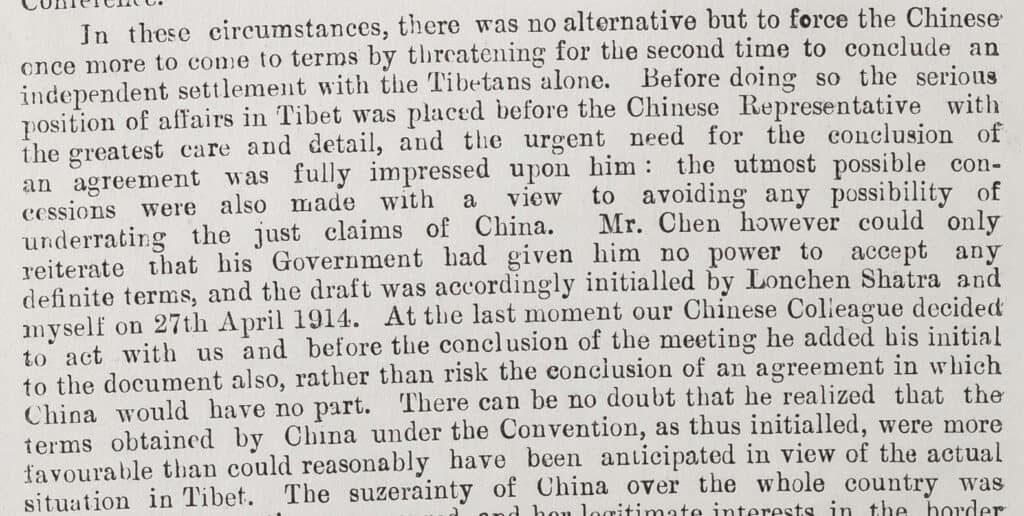

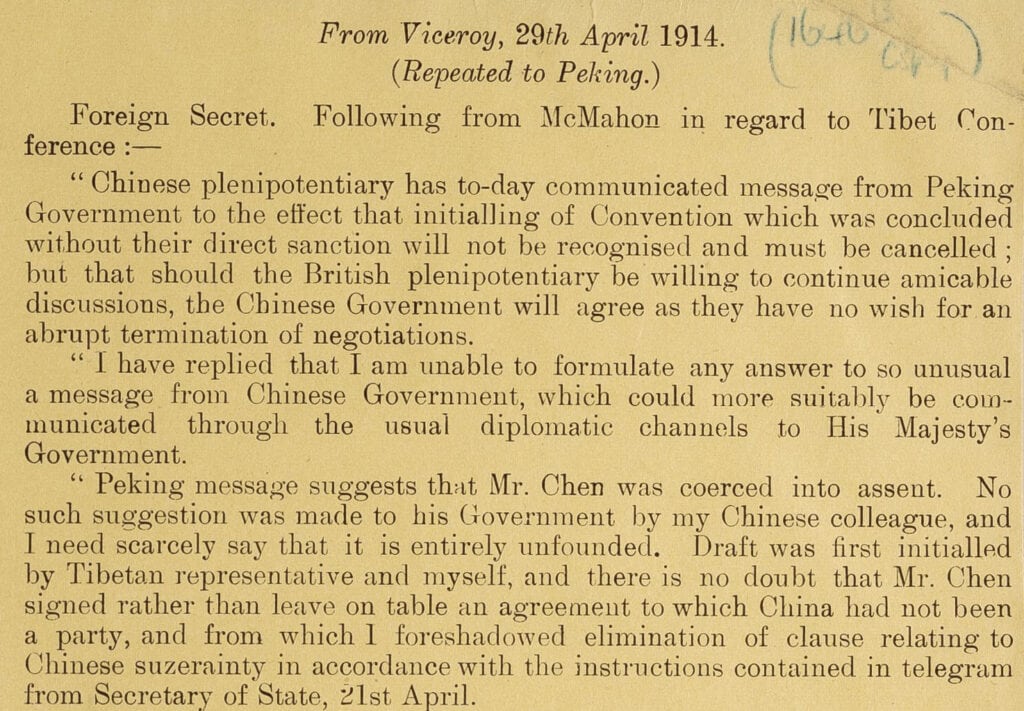

However, the three parties had not reached an agreement by the end of March 1914 because China rejected both the first draft and the revised one due to terms that demanded more concessions than it could make. So McMahon decided “to force the Chinese . . . to come to terms by threatening . . . to conclude an independent settlement with the Tibetans alone.” Under the British pressure, the Chinese representative Ivan Chen “added his initial to the document” after McMahon and Lonchen Shatra had done the same on April 27, 1914.

Two days later, however, the Chinese central government announced her stand by refusing to recognise the initialed convention “without their direct sanction” and called for its cancellation.

The conference continued till July of 1914 and ended with only Britain and Tibet concluding the nominally tripartite convention on Tibet. At the same time, Britain and Tibet also signed a declaration that the convention would be binding on both parties, and a set of new trade regulations that granted British merchants the rights to export goods, especially Indian tea, to Tibet without duty.

It is true that defining the boundaries between China and Tibet and China’s rights in Tibet were the main items on the agenda of the Simla Conference, and had attracted most of the attention and energy of the delegates. However, some other “subsidiary but important issues” had been negotiated between British India and Tibet during the conference, separately and privately, without Chinese approval. On top of the new trade regulations, the two parties agreed on a boundary along India’s north-eastern frontier.

The McMahon Line

The proposed India-Tibet boundary refers to an 830-mile-long line of demarcation stretching from east of Bhutan all the way to the Irrawaddy River to the east. As it was proposed by the British plenipotentiary, it was later named after him – the McMahon Line – and has been in use till this day. In Enclosure 3 to his final memorandum on the Tibet Conference, McMahon himself asserted that “this definition of the Indo-Tibet frontier [is] not the least important and valuable of the results which have been achieved by the work of the Conference.” What were the main considerations behind the demarcation of this boundary? And what advantages did British India expect to gain out of it?

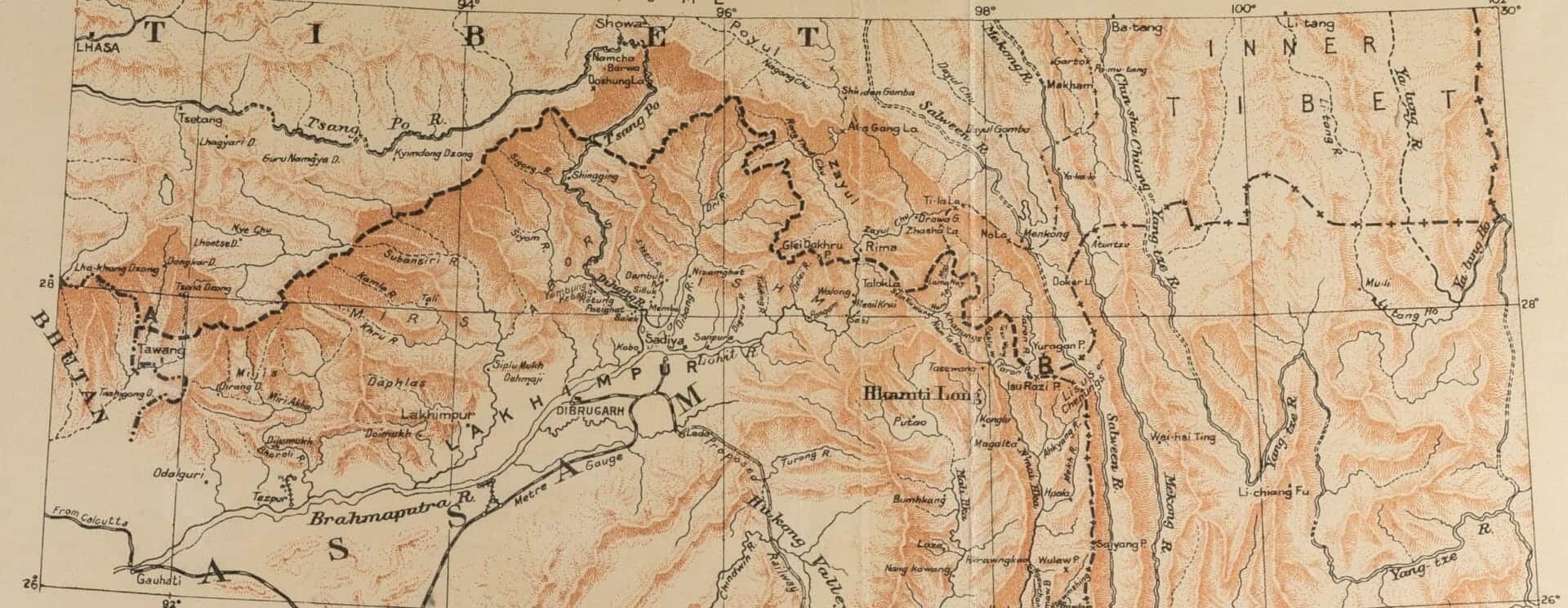

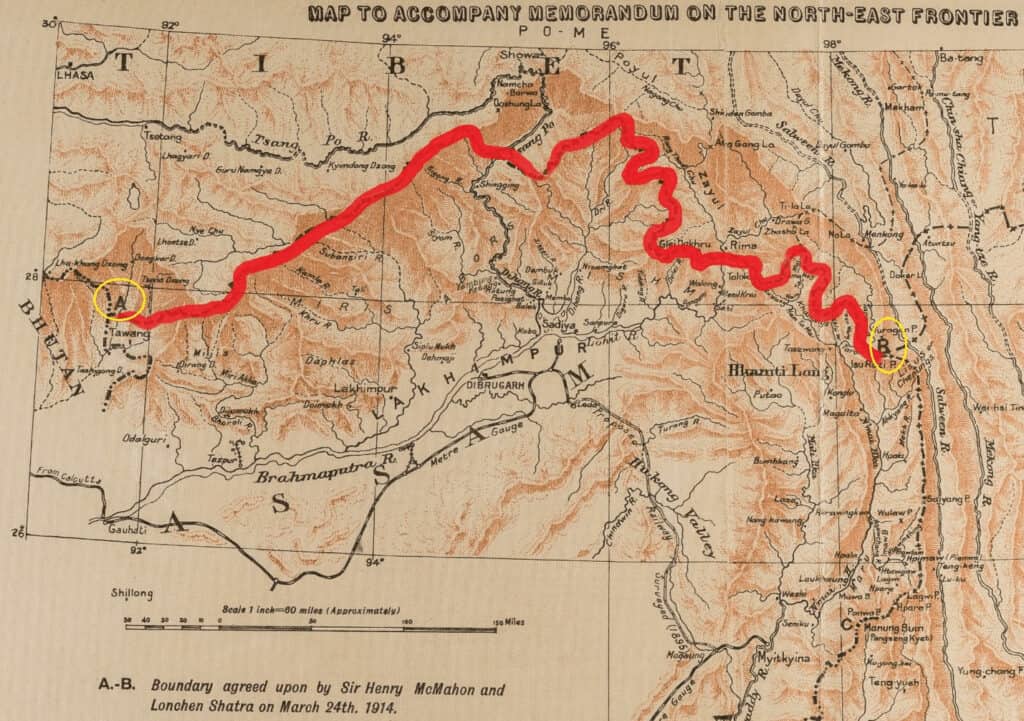

The traditional north-eastern frontier between India and Tibet consists of a mysterious and almost inaccessible belt of uplands inhabited by the Abor, Mishmi, Miri and Kampti tribes. Thanks to the British geographical and military expeditions completed during the three years prior to the Simla conference, British India had acquired a better understanding of the area. It was based on such new knowledge that McMahon proposed a clearly defined boundary line with Tibet that would incorporate the entire belt area into the Indian territory. Through several rounds of negotiations with Tibet, McMahon successfully coerced Tibet—who badly needed British support and help in its confrontation with China—into accepting the proposal. The boundary line was indicated clearly as the section from A to B in the second map attached to the Convention signed only by Britain and Tibet (see image below; red line and yellow circles added by author).

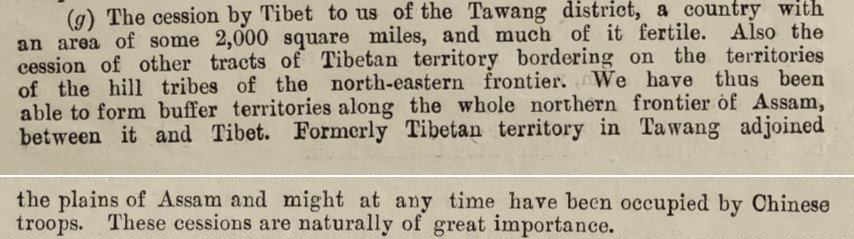

Regarding the significance of this boundary, McMahon briefly commented that it would “meet administrative needs and provide political safeguards along an extended belt of trial country between India and Tibet.” C. A. Bell, British political officer in Sikkim who was also involved in the Simla Conference as McMahon’s aide, offered a more apt summary of the benefits and gains the boundary would bring about for Britain in a confidential report dated August 6, 1915 to the Secretary to the Government of India in the Foreign and Political Department:

Apparently, the British representative forced the Tibetan government to cede a vast tract of its territory to India through the McMahon Line. The Tawang district—located near the western end of the McMahon Line and forming only a small part of the ceded territory—alone covers an area of around 2,000 square miles. These ceded lands would provide “buffer territories along the whole northern frontier of (the Indian province of) Assam, between it and Tibet,” effectively preventing the advances of Chinese troops. So, for Bell, these cessions “are naturally of great importance.”

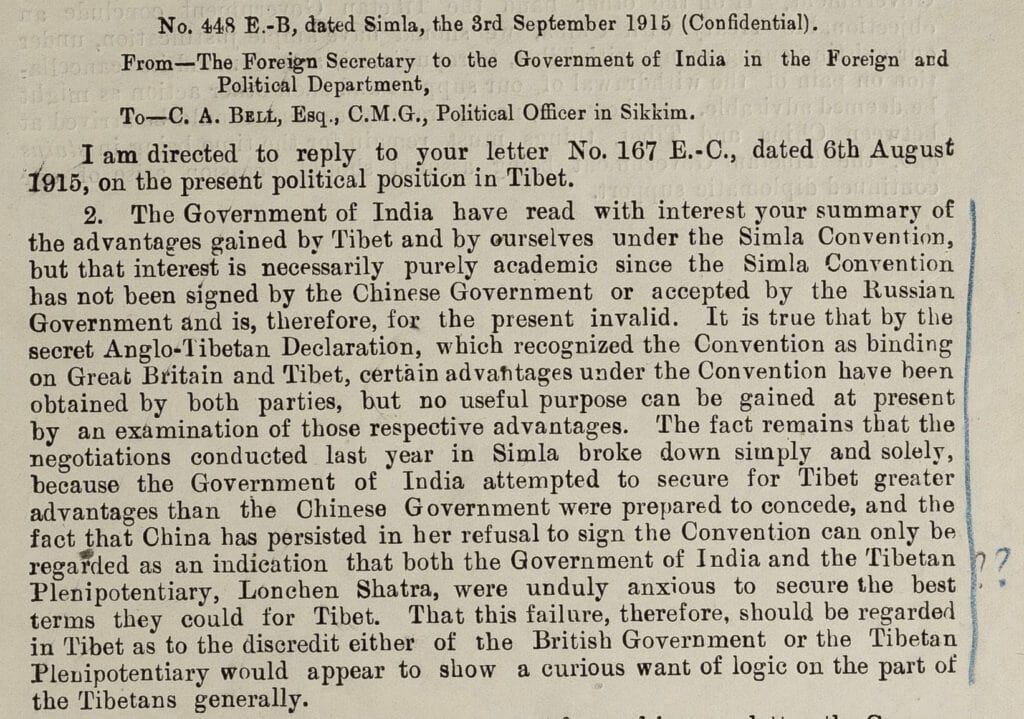

What did the British/Indian government think of these “advantages”? In his reply to Bell’s report, the Foreign Secretary to the Government of India in the Foreign and Political Department stressed that those advantages were “purely academic since the Simla Convention has not been signed by the Chinese Government or accepted by the Russian Government, and is, therefore, for the present invalid.”

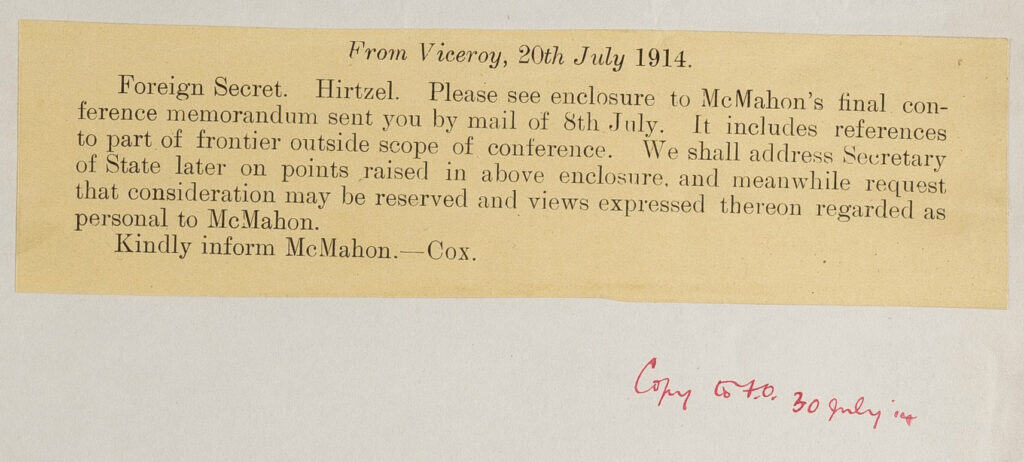

Actually, as early as July 1914, in his comment on McMahon’s final memorandum on the Simla Conference, the Viceroy or Governor-General of India pointed out that the memorandum “includes references to part of frontier outside scope of conference. We shall . . . request that consideration may be reserved and views expressed thereon regarded as personal to McMahon.”

In other words, many high-ranking officials within the Indian and British governments remained cool-headed and wary about the validity of McMahon’s ambitious proposal for demarcating the boundary with Tibet.

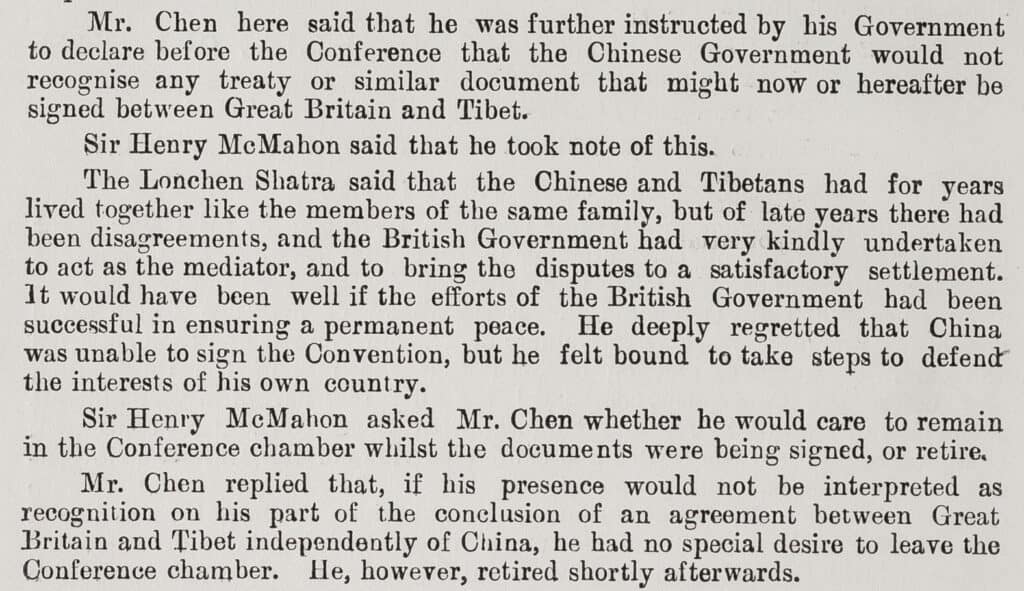

At the same time, it needs to be noted that the Chinese government declared on July 3, 1914, during the eighth meeting of the Simla Conference through Ivan Chen, that it would not “recognise any treaty or similar document that might now or hereafter be signed between Great Britain and Tibet.”

After the Simla Conference, the Chinese government tried a few times to reopen the negotiations on Tibet, but the British declined the request for various reasons, such as the ongoing First World War. As such, the tripartite convention drafted for the Simla Conference was never formally concluded due to China’s rejection of the terms and so all the related proposals on the boundaries between China and Tibet, and between British India and Tibet, never received the official government recognition of either China or Britain.

The Situation Since Indian Independence

This contentious boundary was inherited by the post-independence Republic of India government, evolving into a colonial legacy that has continuously shaped its relations with the People’s Republic of China since the late 1940s. India renamed the disputed area along the McMahon Line the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA). Adopting a “Forward Policy” under the sway of Indian nationalism and anti-Chinese sentiments, the Nehru administration set up many military outposts in the disputed area in the early 1960s, which led to heightened tensions with China and eventually the outbreak of the Sino-Indian War in 1962.

The war has further aggravated the bilateral relations. India renamed NEFA Arunachal Pradesh in 1972, while China refers to the areas as South Tibet. Border disputes have since erupted periodically despite the two governments’ attempts to solve the boundary issues that are largely traceable to the notorious McMahon Line.

If you found reading about the Tripartite Conference at Simla, the McMahon Line and the origins of Sino-Indian border disputes in this blog post interesting, you might like:

- Rediscovering China and the World in the Nineteenth Century

- Indentured Indian Workers and Anti-Colonial Resistance in the British Empire

- Sun Yat-sen and the Kwangtung–Kwangsi Conflicts in the 1920s

- Dr. Sun Yat-sen, the man who led China from Empire to Republic

- Researching Infectious Diseases in Colonial India