│By Amelie Bonney, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford│

Most of us see bright-feathered, warbling canaries as pets, yet these tiny birds were not always just household companions. In the nineteenth century they were used as exceptional risk predictors in mines. This was because they were particularly sensitive to carbon monoxide, a substance which led to numerous mining accidents in the aftermath of industrialisation. Thus, oddly, an increasing reliance on fossil fuels induced a new rapport with nature and animals. The canary’s role in mines became so engrained in the English language that “a canary in the coalmine” is now a well-known phrase, used to refer to early indicators of potential hazards. Gale’s Historical Newspapers allow us to better understand how the canary came to be emblematic of shifting attitudes towards risk during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in the English-speaking world.

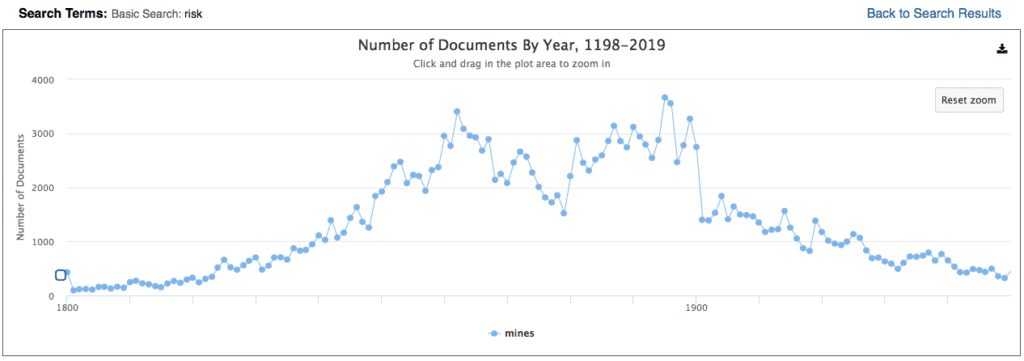

Risk management in mines became a major source of concern during the nineteenth century. The Term Frequency tool in Gale Primary Sources shows a great rise in discussion in the press about mines and risk between 1850 and 1900. While this upsurge of articles is also a direct consequence of the rising production of newspapers, it is also representative of increasing awareness of the risks tied to mining and attempts to reduce them through the use of (supposedly) safer equipment and risk-prediction technologies.

The life-saving bird

In the nineteenth century, coal mining developed into a vital industry, as steam engines and railways became increasingly widespread. Whilst new technologies allowed deeper and deeper mines, miners were exposed to increasingly dangerous working environments and often fell victim to explosions and poisonous gases. Carbon monoxide is a particularly deadly gas as it is not only odourless and colourless, it’s lighter than air and highly flammable. It can also quickly build up in the body, which made it essential to find ways to swiftly detect its presence in the air. It was soon discovered that a canary would immediately show signs of distress in the presence of carbon monoxide and die well before a human would begin to feel the effects of carbon monoxide poisoning, thus they came to play a crucial role in detecting these toxic gases and managing hazards in the mine.

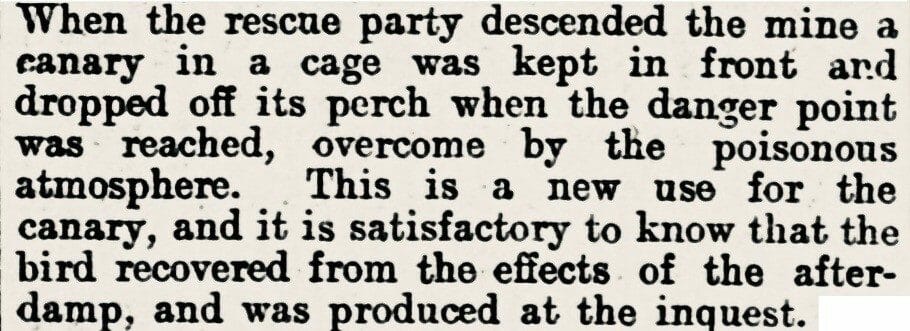

The practice began in the last decades of the nineteenth century. In 1906, canaries were used by a rescue team to enter a mine in the aftermath of an explosion (see below). The canary was described as most useful and in some instances they were produced as evidence during investigations of industrial accidents. By 1911, regulations insisted that miners should “use ‘two small caged birds’ each time they went down a mine”.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/JE3240485514/GDCS?u=webdemo&sid=GDCS&xid=87ba73d1

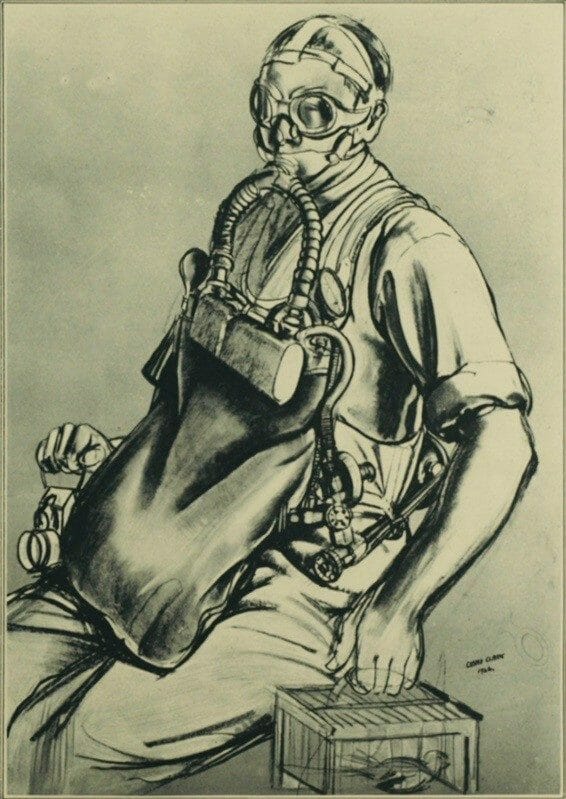

As the canary became an increasingly popular aid for risk prediction, it even started to be described as a “scientific adjunct to coal mining”. By 1926, the canary had become a typical attribute of the rescue teams that went into mines in the aftermath of accidents, as can be seen on drawings that were created during a nine-day nationwide general strike of coalminers in the UK in 1926.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/HN3100271756/GDCS?u=oxford&sid=GDCS&xid=fd1a92c9

However, in the same year, Dugald Macintyre argued that it was deplorable to use the birds for this task, and considered it a failure of science that no tool had yet been invented to spare the animals from being taken into the mine pits. Macintyre did acknowledge, however, that canaries proved essential to save lives during the Scotswood Colliery disaster in Northumberland in 1925, and insisted that the birds were “uniformly well cared for”.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/JF3228390891/GDCS?u=oxford&sid=GDCS&xid=1c47fd47

Interestingly, this article, found in Gale’s British Library Newspapers, explained that contrary to what is commonly believed, canaries were not the preferred birds for this mission, and instead claimed that wild redpolls were more reliable because they were “more active, and more sensitive to the effects of gas than cage-bred birds”.

While these tales of canaries in mines might seem to belong to a distant past, canaries were actually used in mines as late as 1996 when British legislation officially ordered miners to replace canaries with electronic carbon monoxide sensors. Miners themselves however regretted the loss of their canaries, as reported in this article in the Daily Mail Historical Archive:

Daily Mail Historical Archive

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/EE1860550990/GDCS?u=oxford&sid=GDCS&xid=1f1e2b3a

While new equipment was considered safer by authorities, miners themselves pointed to the reliability of the canaries, arguing that “batteries can fail – canaries don’t”.

Canaries and warfare

With the use of poisonous gas in warfare in the twentieth century, the canary became a highly valued asset on the battlefield. Due to their use in coalpits, several experiments showed that canaries could detect specific poisonous gases. Considered as a “cheap and sensitive warning device in warfare”, they were first used during the First World War, so much so that they appeared in war memoirs such as this one included in Gale’s British Library Newspapers.

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/JA3238334599/GDCS?u=oxford&sid=GDCS&xid=8da81ff8

In the context of the First World War, the escape of a canary could seriously undermine long-term efforts against the enemy. If a mining canary was discovered by opposing forces, it indicated the presence of a nearby mining operation and would mean “the undoing of the work of weeks”. As a result, it became crucial to immediately shoot any bird that escaped.

Canaries were used to detect poisonous gases well into the twentieth and even twenty-first centuries. They were used during the Gulf War, where they were “code-named Elvis – Early Liquid Vapour Indicator System,” and were used to detect a toxic gas following a terrorist attack in Japan in 1995:

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IO0701590037/GDCS?u=oxford&sid=GDCS&xid=c213349d

Similarly, after 9/11 sparked fears amongst New Yorkers about a chemical terrorist attack, The Times reported that “canary breeders could barely keep up with demand”. As recently as 2003 during the Iraq War, the Financial Times reported that canaries were in high demand in Baghdad, where they were considered as “the only chemical weapons detector available” for the local population. Even if canaries are no longer used in mines, their sensitivity to poisonous gases remains valued in a number of different contexts today.

The canary in the coalmine: a symbol of risk

Over the past decades, the canary in the coal mine has become emblematic of risks and failures in the political, economic and cultural domain. In 2010, the International Herald Tribune viewed the music industry as “the canary in the digital coal mine”, explaining that it served as a warning to what would happen to other art forms with the normalisation of internet connections. The phrase is also repeatedly used in political contexts; Scotland, for example, is referred to as “the canary in the United Kingdom’s coal mine” in the context of debates on the Celtic fringe. The analogy was also used in debates on gender and liberty in Iran in 2010:

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/IF0504153572/GDCS?u=oxford&sid=GDCS&xid=95c3457b

Most often however, the image of the canary in the coal mine has become associated to human sensitivity to toxic elements and is used to arouse awareness of environmental problems. It can be encountered in accounts of environmental illness, where afflicted individuals feel like the little birds that were once so sensitive to the particular environment of the coal mines. Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender provides insights into some of these accounts, such as that of Havey Betty.

vol. 8, no. 12, 1995, p. 4, Archives of Sexuality and Gender

https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/WDRVFI654047899/AHSI?u=webdemo&sid=AHSI&xid=bc865662

In some cases, the fear of chemically altered environments and pollution can become extreme. In 1992, Caroline Richmond described individuals calling themselves “human canaries” who believe that they are “so sensitive to modern chemicals that they will die unless they live in isolated bubbles”.

While new tools have long replaced the canary in mines, risk management remains a constant source for concern in the industrial world and the image of the “canary in the coalmine” has come to be tied to a range of political, cultural, economic and environmental concerns. Even though risks have become an integral part of industrialised societies, the proliferation of toxic substances affecting living organisms and the environment in general means that some people now view themselves as canaries in a global coal mine.

If you wish to learn more about animals in industrial environments and the history of risk management, or if you are an Oxford student or researcher wanting to learn more about ways in which you can use Gale Primary Sources for your own research, feel free to contact me via Twitter (@BonneyAmelie).

Interested in reading more about historical scientific practices or the discourses and symbolism that can emerge around animals? Check out Explaining Volcanic Eruptions from the Late Eighteenth Century to the Modern Day and The Myth of the Rhinoceros.

Blog post cover image citation: Reiblein, Emily. “Canary in a Coal Mine.” Marine Log, vol. 122, no. 9, Sept. 2017, p. 7. Gale OneFile: Business, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A512184846/GPS?u=webdemo&sid=GPS&xid=086f9b8b