│by Constance Lam, Gale Ambassador at the University of Durham│

Constructed in 2000, the Liverpool Chinese Arch remains an important landmark of Liverpool’s Chinatown. Standing at 13.5 metres high, this arch is the largest Chinese archway in Europe thus far, the impressive height reflecting the fact that Liverpool is home to the oldest Chinese community in Europe. On the twentieth year since the construction of the Chinese Arch, this blog post will look back on the rich history of Liverpool’s Chinatown.

Using Gale’s Topic Finder Tool

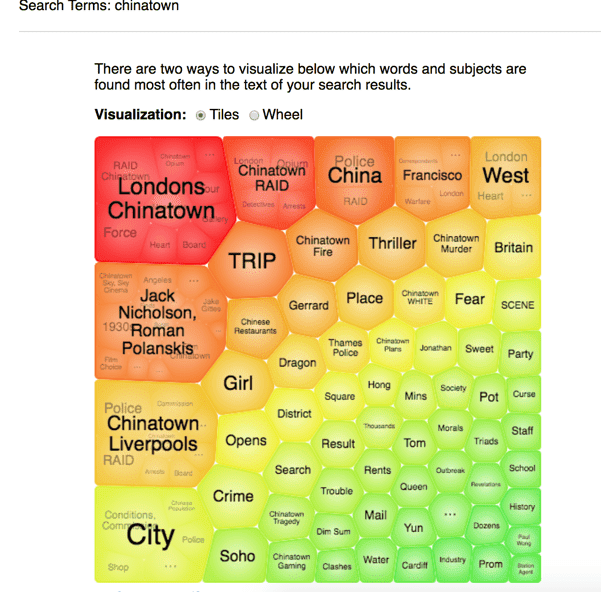

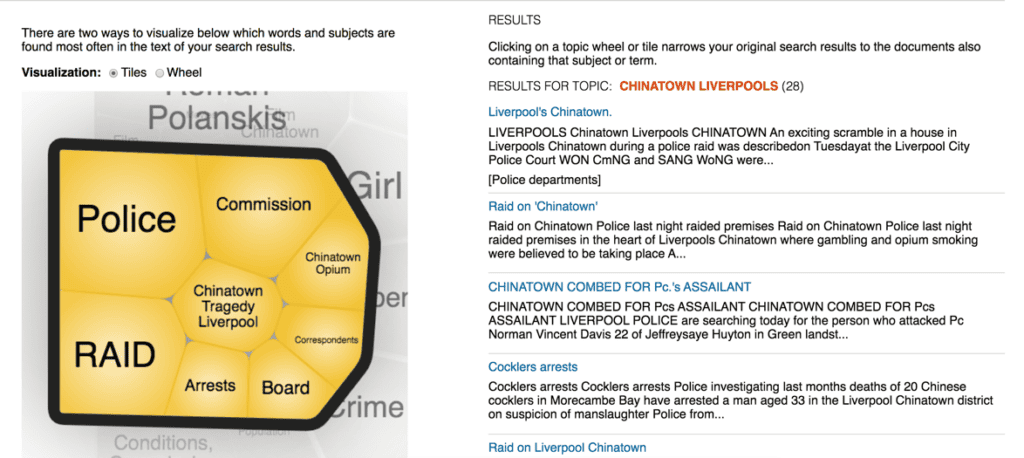

Prior to writing this post, I knew that I was interested in writing about Chinatowns in the UK, but I needed to find a more specific angle. I decided to use the Topic Finder tool to help me narrow down my topic. Immediately after I did this, a wide selection of topics became available to me!

I noticed that “Chinatown Liverpools” was a significant part of the topic wheel, and I was curious to learn more. After clicking on the tile, I was able to see 28 results about Chinatown in Liverpool. The tool was helpful as it also showed me the recurring topic areas of these search results, including “raid”, “Chinatown opium”, and “arrests”. Once I went through the sources, I decided to take a chronological approach.

Chinese Immigration into Liverpool

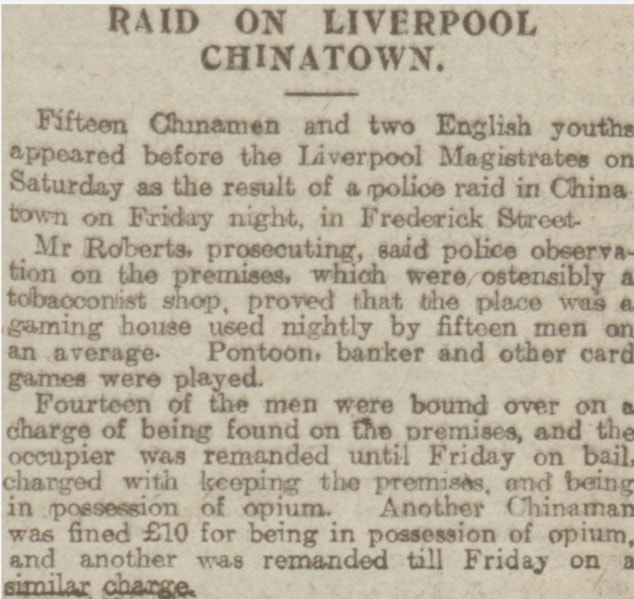

I first clicked on this article from the British Library Newspapers archive. Published in 1906, it is titled “Chinese Immigration Problem”. As the title suggests, it was about “a renewal of public indignation” surrounding the arrival of a new wave of Chinese immigrants into Liverpool. Such hostility towards Chinese immigrants was common, and there were many police raids aiming to identify undocumented immigrants. From the same archive, this 1928 article titled “Unregistered Chinese” writes: “It is stated that many Chinese enter the country and become engaged in various activities without registering in the Aliens Act and the fear is entertained that some of them may be employed in the illicit smuggling of goods into the country.” This article is likely referring to the possession of opium in Chinatown: those in possession could be remanded or liable to a £10 fine, as seen here.

Another example of a larger-scale opium raid is detailed in this article of 1928: a British widow was found possessing 22 pounds of opium worth £400. From the article, I learnt that this widow was “fined £5 for aiding and abetting” three Chinese people selling opium, resulting in their deportation. If an immigrant were to be implicated in the possession of opium, it is without a doubt that the consequences they faced would be more severe than a British national.

Social Change in Liverpool’s Chinatown

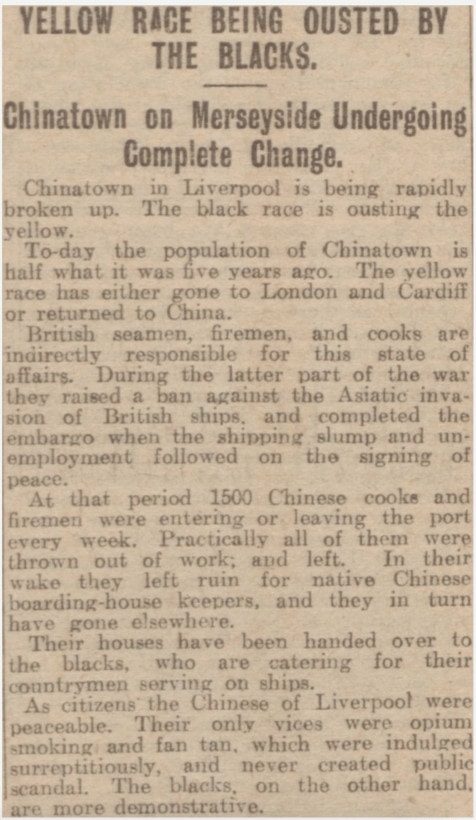

I also found various sources which show how the demographics of Liverpool’s Chinatown were impacted by different events. One was this article, also from the British Library Newspapers archive, from 1921, with the provocative and anachronistic headline “Yellow Race Being Ousted by the Blacks.” The article stated that the population of Chinatown was “half what it is five years ago” due to a rise of unemployment after the signing of peace. It then proceeds to make sweeping racial generalisations: “As citizens the Chinese of Liverpool were peaceable […] The blacks, on the other hand, are more demonstrative.” The racial bias of this source was very prominent, and I knew that I needed to examine other sources.

Rebuilding Liverpool’s Chinatown after WWII

Moving on chronologically, I came across this source from The Times Digital Archive reporting that a Chinese architecture student aimed to rebuild Chinatown following the damage of World War II, which had dispersed the Chinese population to various areas of the city. Significantly, the student’s professor believed that such a scheme “should be emulated by London, Cardiff, and New York” – also cities with large Chinese populations.

A thriving and growing community

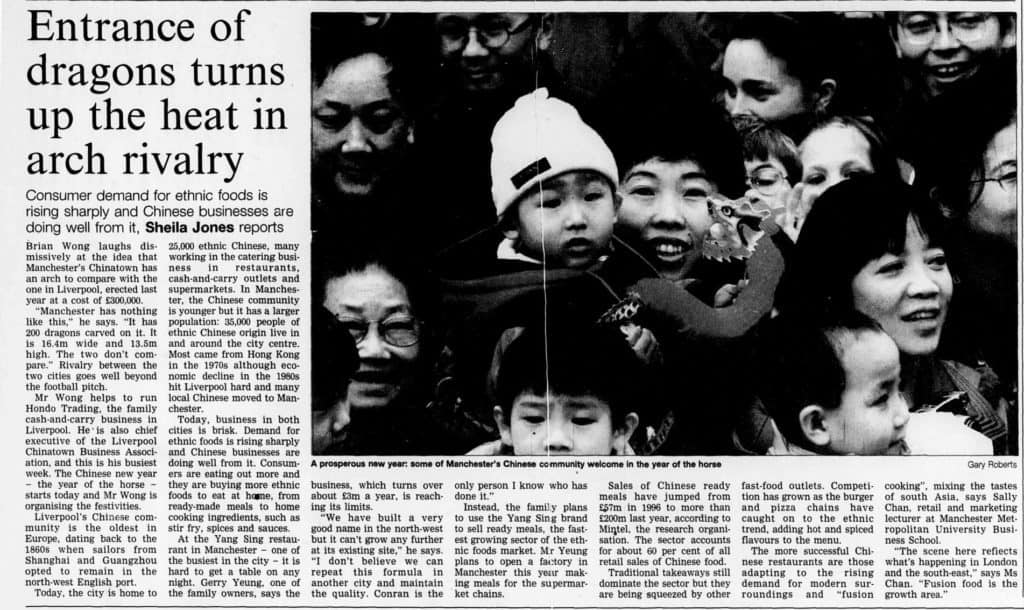

However, World War II was not the only challenge Liverpool’s Chinatown has faced. This 1992 article from The Independent Historical Archive informs us about the collapse of Charterhouse, a property firm owning a commercial quarter comprising Bold Street and Duke Street, both of which are part of Liverpool’s Chinatown. The article includes the conclusion of the planning report by the council: “Institutionally, Liverpool is still not entirely comfortable with Chinatown.” However, an article published a decade later in 2002 paints a very different picture: “Demand for ethnic foods is rising sharply and Chinese businesses are doing well from it.” Today, the Chinatown in Liverpool appears to be a thriving and growing community.

If you’re interested in learning more about the history of Liverpool’s Chinatown, please check out any of Gale’s archives mentioned in the blog post, and this website also contains a lot of useful information.

Interested in learning more about the social history of Liverpool? Check out: Liverpool: a City Overshadowed by the Beatles?, Trouble in Toxteth: Representations of the 1981 Riots in Liverpool in the National Press or Exploring perceptions of Liverpool’s International Slavery Museum using Gale Primary Sources. Or how about representations of Chinese immigration? Check out: The Chinese diaspora during China’s transformation from Empire to Republic: experiences in five different regions.

Blog post cover image citation: Liverpool’s Chinese Arch, Bob Edwards via Flickr, taken on November 11, 2015.