│by Matthew Trenholm, Gale Ambassador at the University of Exeter│

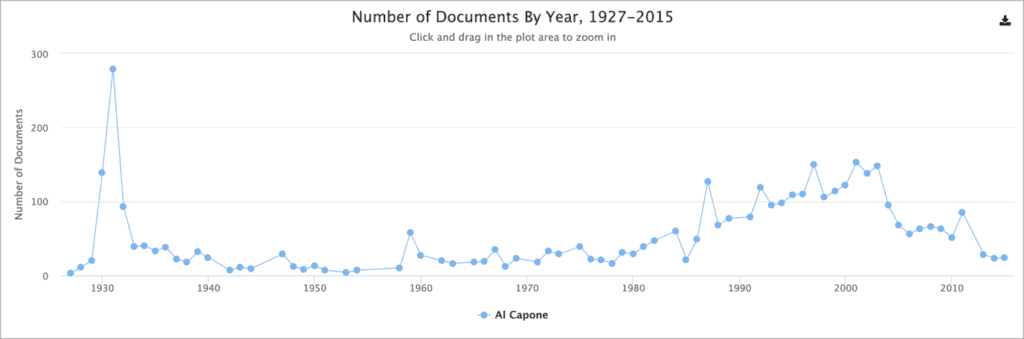

Everyone loves a villain. From Robin Hood to the Peaky Blinders, criminality has long captured the imagination of the British public, with the misdeeds of the real outlaws often swept under the rug. (For an engaging piece about the historical accuracy of the TV show Peaky Blinders, check out this blog post by my fellow Gale Ambassador, Emily Priest – it’s great!) American organised crime enjoyed a “golden era” in the 1920s after Prohibition was introduced in 1919. Bootlegging became a big industry in the US as the economy boomed and cultural norms changed. Contemporaries in Britain loved to hear stories of the criminals taking on the law, and this is reflected in the upsurge in coverage of such criminals in the British press.

Glamorous Gangsters

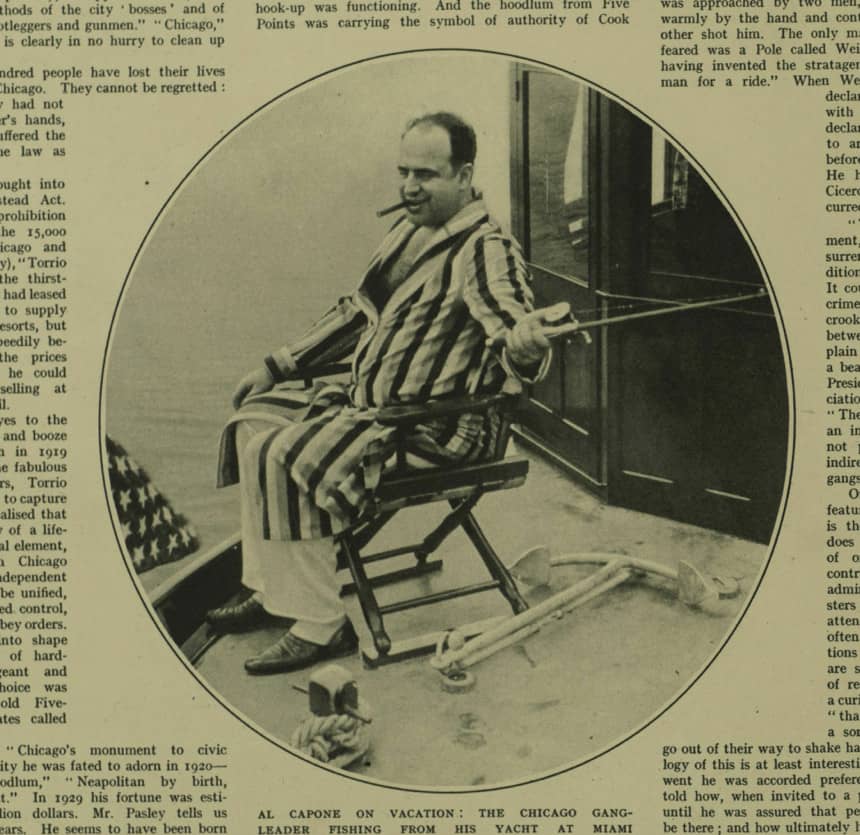

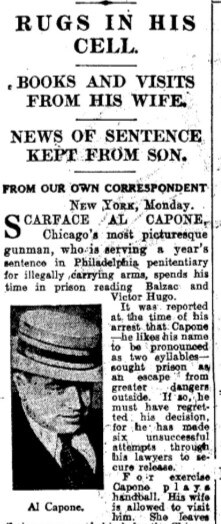

It is impossible to start anywhere but with Al Capone, the most notorious and, according to the Daily Mail’s own correspondent on 10th December 1929, the “most picturesque” of America’s gangsters. In this context, “picturesque” meant stereotypical. Indeed Al Capone, nicknamed “Scarface” has endured in the popular imagination as the archetype of a 1920s gangster for more than eighty years.

A fan of fishing and Balzac, his criminality was mostly glossed over by the Daily Mail and The Illustrated London News in favour of discussing his hobbies and the sadness he felt by being away from his son. Capone had competition though from Linky Mitchell in New York who was similarly “picturesque” and had interesting hobbies too according to his obituary: his pet pigeons were the priority.

Overwhelming corruption

Capone was an institution himself, and the UK media loved to poke fun at American gangster culture. His takeover of the Chicago crime scene after prolonged and violent battles with other criminal groups in the early 1930s was described by the Daily Mail as “a giant merger” and he appointed a “cabinet” to oversee the areas of beer, war and gambling. The hapless police were powerless to stop this development but that may have something to do with the overwhelming corruption of the period – in Linky Mitchell’s home town of New York, a former police commissioner estimated that around 100,000 speakeasies “furnish graft” (paid bribes) of around £22,000,000 each year for “police protection” (a staggering £1.2 billion in today’s money), yet were making profits of around £230,000,000.

Keeping it in the Family

It was not just Capone himself who was in the international spotlight: the sprawling crime families in Chicago attracted interest akin to that of the British royal family. Mafalda Capone’s wedding photos made it into both The Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph in the UK. The wedding itself was a tame affair – only five arrests were made! Like the arranged marriages of old aristocratic families, the match was meant to cement an alliance between Capone and his former rival, Frank Diamond.

A brutal profession

Despite the positive depiction gangsters received in much of the mainstream press, one cannot simply ignore the fact that the violence of their profession was brutal. An account from the Wood Detective Agency Records (found in Gale’s Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture 1790-1920) describes a police officer being gunned down outside a speakeasy – the establishments that sprang up to provide a place for Americans to enjoy a drink while Prohibition was in effect – and Linky Mitchell met his own violent end within one of his own establishments.

The Youth of Yesterday

Some moralists did choose to lecture their readers about the dangers of speakeasies. They claimed the enterprises were part of a culture suffering from ‘sex, pollution and human decay’. In one of many articles that can be found in Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender, Paul Yawitz took his readers on a journey through the sleazy streets of Greenwich Village in New York City. He was particularly angry about the apparent corruption of young New Yorkers, both male and female alike. These documents provide an insight into the perceptions different groups in society had of New York nightlife in the 1920s and touch on the response to marginalised communities like LGBTQ+ New Yorkers who are largely absent from the historical record.

Here to help!

Every archive available on the Gale Primary Sources platform is bursting with incredible stories that deserve to be told. Plus, as the cross-search platform brings them together in one place, it is easy to explore the full range of resources available, and harness the power of the Gale archives to create entertaining and original research. If you’re a student at the University of Exeter and you want to learn more about how to use Gale’s archives to enrich your research for essays and other assignments, then get in touch with me via Twitter ( @Matt_Trenholm) or contact the Gale Resources at the University of Exeter Facebook Page. While investigating the golden age of American organised crime, I found a fascinating world full of corruption, politics and pigeons – I’d love to know what you find in the Gale archives!

Blog post cover image citation: Mack Sennett Comedies / Paramount Pictures [Public Domain], Still from the American comedy film The Speakeasy (1919), on p.109 of the December 27, 1919 Exhibitors Herald. The film was a humorous take on Prohibition in the United States. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Speakeasy_(1919)_-_1.jpg