By Lyndsey England, Gale Ambassador at Durham University

In 1769, writing his ‘Description of Three Hundred Animals’, a document included in Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online, Thomas Boreman presented the rhinoceros as follows:

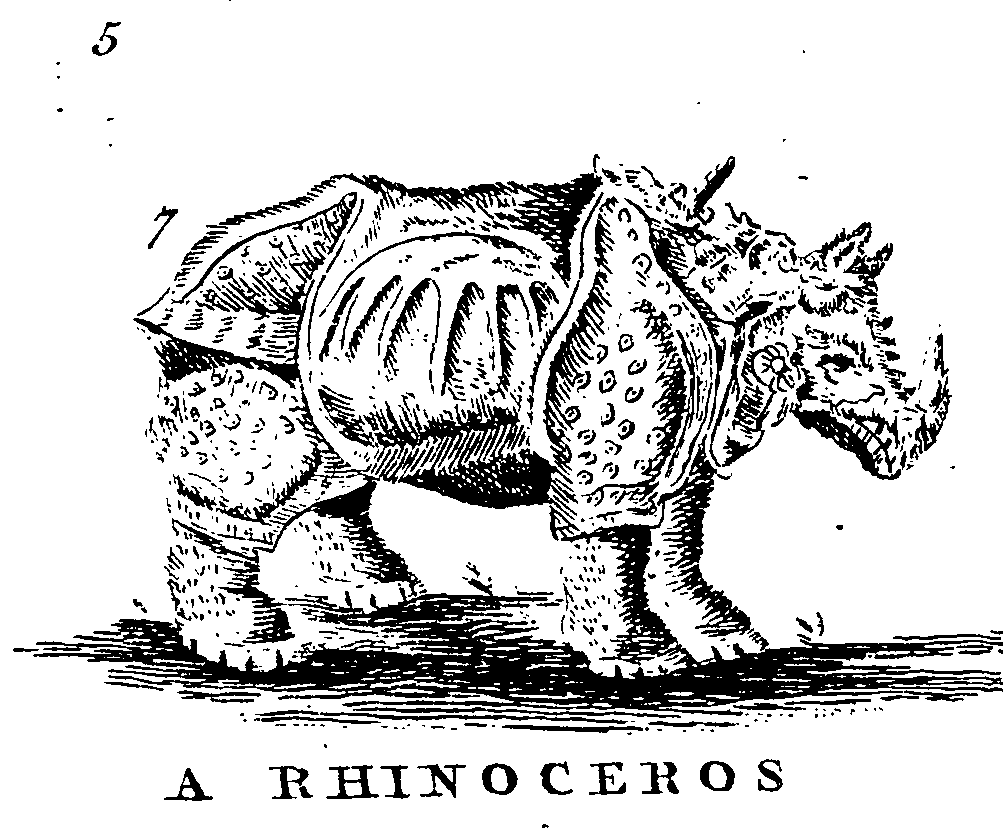

“He has two girdles upon his body, like the wings of a dragon, from his back down to his belly … his skin is so hard, that no dart is able to pierce it, and covered over with scales, like the shell of a tortoise.”

Accompanying this fantastical description is a sketch of the armoured creature beside another well-famed although mythological beast, the unicorn:

![Thomas Boreman. A description of three hundred animals, viz. beasts, birds, fishes, serpents, and insects. With a particular account of the manner of their catching of whales in Greenland. Extracted from the best authors, and adapted to the Use of all Capacities. Illustrated with copper plates, whereon is curiously engraven every Beast, Bird, Fish, Serpent, and Insect, described in the whole Book. 10th ed., printed for H. Woodfall, J. Rivington, R. Baldwin, Hawes, Clarke and Collins, S. Crowder, T. Caslon, and Robinson and Roberts, MDCCLXIX. [1769]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online,](http://blog.gale.cengage.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/Rhino-2-593x1024.png)

Considering other early accounts of the rhinoceros, this sad reality is difficult to fathom. In his ‘Natural History of Beasts’, Stephen Jones drew attention to the rhinoceros’ brute strength:

‘The tiger will more willingly attack any other enemy’ than the rhinoceros, he wrote. ‘It is defended on every side’ with skin that ‘cannot be pierced by the claws of the lion or the tiger’. Despite this, an animal as physically weak as man has thwarted the impenetrable ‘thick thorny hide’ that had otherwise protected this creature for centuries, transforming it from a ‘formidable creature’ into a critically endangered one.

The ‘weapon’ that Jones outlines as the rhino’s chief means of defence has been transformed into its greatest weakness – its horn.

Magic Virtue

Popular discourse on the rhinoceros has frequently revolved around the animal’s magical properties.

Moving away from the eighteenth-century collections, its close affiliation with the unicorn has been outlined even in more modern times, and it is this fantastical presentation of the animal which has contributed largely to its decline. In transforming the rhino into an object of magic and wonder, the world has conspired against it.

As the Times outlined in 1934, ‘the rhinoceros is not the unicorn, but he has been confused with him’ and therefore has been made to pay the price of our childhood fables.

Of course, these perceptions are not limited to the Western world. Most notably, in the Far East, the mythology surrounding the rhinoceros is extensive. In the 1800s, in a periodical entitled The China Review: Or, Notes And Queries On The Far East (now included in Gale’s Archives Unbound collection 19th Century English-Language Journals from the Far East), one of the magical uses of rhino horn is described as follows:

‘A Dark Side to the Tale’

With this persuasive storytelling casting a long shadow over the rhinoceros’ future, it is no surprise that numbers are dwindling. Coupling this with the emergence of a modern folklore that stipulates powdered rhino horn can cure cancer, rhino poaching has increased dramatically.

Despite governments implementing severe laws regarding the trade of rhino horn, protecting the species remains difficult. As The Economist noted in 2011, ‘such heavy-handed law enforcement undermines support for conservation among locals’.

“On the horn of a dilemma.” Economist, 7 May 2011, p. 58. The Economist Historical Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/96h2g3

It seems as though, even at its most vulnerable, the rhinoceros cannot shake its persona as an intimidating beast – something captured visually in the cartoon above. Unless the fragility of the rhinoceros is truly absorbed into global consciousness soon, these creatures will, in time, be entirely lost to the fables that have given them their fame.