│By Maya Thomas, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford│

The weather is cold and grey, but the shops are ablaze with red hearts, sparkly roses and giant teddy bears holding signs reading “I love you”: Valentine’s Day is upon us yet again. Whether you love or hate this centuries-old festival, it cannot be denied that the love it celebrates certainly deserves a day of its own. After all, from Helen of Troy to Tinder, the literary-minded (read: soppy) historian might argue that love, with all its greatness and tragedy, has inspired the culture, art and even politics that have propelled our human story onward.

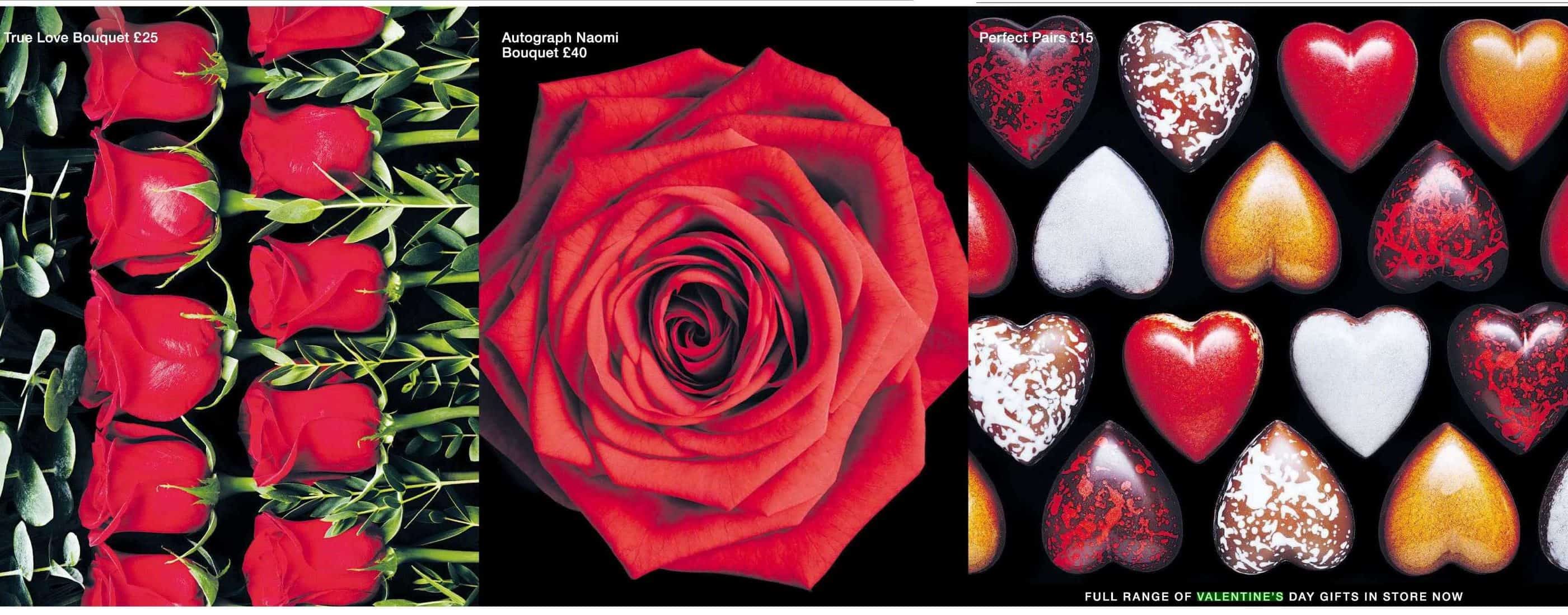

Yet anyone who’s ever wandered forlornly through the maze of hearts and roses that adorns our Western shopping centres at this time of year, and longingly gazed at some elaborate box of heart-shaped chocolates wishing they had someone to buy it for, can tell you that even a festival celebrating something as joyful as love inevitably has a darker side.

“LIDL.” Independent, 12 Feb. 2016, p. [14]. The Independent Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/97xk70

While I was initially going to ignore this more negative side and simply write an article on the history of St Valentine’s day, I recently joined the ranks of the heartbroken and so I did what every History undergrad with a flair for the dramatic might do: I decided to research the historical documentation of heartbreak instead. After all, in a strange way, I’ve always found comfort in knowing that throughout history, hundreds of generations of people like myself have experienced and dealt with the many emotional bullets fired at us by life’s machine gun (a lovely image, I know).

As I entered the term “heartbroken” into the Gale Primary Sources search box, I expected to find a wealth of poetic romantic rants, dramatic ballads about lost loves, and perhaps the occasional humorous article that I could relate to. I was surprised, however, to find that the results of my search yielded less about the romantic heartache I was experiencing and instead produced a wealth of documents on the many other types of emotional misery people have experienced in their lives. (Yes, if you hadn’t guessed from the title of this article: prepare for a pretty sad read.)

From articles on being heartbroken as a result of the political situation in Korea to grief over the loss of a loyal dog, I found that the extensive range of non-romantic heartbreak in historical documentation was very sobering. On Friday 15th October 1869, for instance, the Morning Republican published an article relating the story of a mother waiting for her soldier son to return from one of his naval campaigns. The piece describes how she, full of hope, goes to the docks holding a clean set of clothes so that her son might change out of his filthy uniform. However, as she searches the bustling crowds muttering in an increasingly desperate voice that “he has not come, he has not come”, the realisation that her son is dead slowly dawns on the reader, though not on her. The article closes with the heart-breaking description of the woman’s body, sitting frozen and glassy-eyed against some old barrels on the wharf, ending with the lines:

Having explored the history of familial heartbreak which Gale Primary Sources offered me with my first search, I still wanted to see how romantically heartbroken people like myself handled their lonesome St Valentine’s Days. Using the Term Cluster Tool to narrow down my search, I came across an eighteenth-century bundle of poems collected “to crown with mirth and good humour the happy day which is called St. Valentine”. Even in this joyful bundle, however, I stumbled across this sad poem, written by a heartbroken woman:

![Browne, G. The Complete valentine writer: or, The young men and maidens best assistant. Printed and sold by T. Sabine, No. 17, in Little New Street, Shoe-Lane, Fleet Street, where printing is expeditiously performed in all its branches on reasonable terms, [1780?]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online,](http://blog.gale.cengage.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/valentines-poem.png)

Indeed, the more pages of apparently happy sources I sifted through, the more I began to encounter similar little snippets of heartbreak scattered silently and inconspicuously between them. Perhaps it is testimony both to the positive spirit of the human mind, and the sheer joy that love brings, that the pain of heartbreak, while monstrous, does not rear its head loudly, but rather chooses to live quietly tucked away between the pages.

As I pondered melancholically over the fate of us heartbroken souls throughout the centuries, I began to think that perhaps Valentine’s Day should not simply be a celebration of romantic love for those in happy relationships. Instead, it should be a day on which we can all reflect on how significant love is as a part of the human experience. So, for those who, like me, find themselves quietly heartbroken this Valentine’s Day, let’s take comfort in knowing that it’s okay for us to feel down. After all, though at times it may seem there’s a lot to be heartbroken about, ultimately, we will only remember such times as short periods between far greater stretches of happiness.

Blog post cover image citation: “M&S.” Independent, 13 Feb. 2015, p. 14-15. The Independent Digital Archive, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/97xsx8