By Calvin Liu, Gale Ambassador at the University of Oxford

Remembrance is repetition.

As Laurence Binyon’s poem, often the highlight of memorial services, puts it: ‘They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:/ […]/ We will remember them.’ Ways of memorialising the world wars, too, seem never to grow old and are reinforced through recurrence. Remembrance is ritualised by each poppy-wearing politician, each BBC documentary, each Ian McEwan novel. The narratives have been retold so many times that they grow hazy and the details blend together – battle trenches upon Maginot Lines. It almost comes as a shock to be reminded that twenty-one years elapsed between the two world wars that we now jointly remember on one day. Twenty-one years during which the world regularly reminded itself of the last great war, before rushing into another. Gale Primary Sources provides a plethora of primary sources that poignantly illustrate how the world wars were both remembered and anticipated during the interwar period.

WWI was memorialised before it was over. Laurence Binyon’s ‘For the Fallen’, the poem I quoted from above, was first published in an issue of The Times on 21st September, 1914 – two years before the Somme, and four years before the armistice. On the same page where Binyon’s ode appeared was a column called ‘The War Day by Day’, which brought daily updates from the frontlines; on a single page of The Times, remembrance is performed immediately next to the events that it is trying to remember. Like many other WWI poems by the likes of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, Binyon’s poem begins the process of remembering during the course of the war itself.

In 1921, over seven years after Binyon penned his poem, Field-Marshall Lord Haig introduced the Poppy Appeal, with the donations going to the British Legion in order to ‘alleviate distress among ex-Service men.’ An article from The Times on the 6th October reports that the appeal was launched because Haig was ‘anxious that November 11 shall be a real Remembrance day’. Another mention in The Daily Mail on the 12th, confirms this anxiety. Captain W.G. Willcox, the organiser of the appeal, was quoted saying that the ‘Poppy Day should not be looked on as a flag day’: the poppies are meant to be a tangible way to show that people ‘have not forgotten the war and the fallen’. The same sentiment that drove Binyon to pre-emptively begin the process of memorialisation translates into an anxiety to properly document, remember and re-examine the war only three years after its conclusion.

An event I read about when researching this topic in Gale’s digital archives, and find particularly poignant, came months before the outbreak of the Second World War. In October 1938 – less than a year before the UK declared war on Germany – the Duke of Saxe-Coburg invited the British Legion to visit Germany over the upcoming Armistice Anniversary. The Times published the reply from the British Legion’s Chairman, Major Sir Francis Fetherson-Godley, who declined the offer from the Nazi official, citing that the Legion was preoccupied with organising the Poppy Day and Remembrance Services in Britain. Hitler had just annexed the Sudetenland the month before and a sense of unspoken tension pervades the Chairman’s reply. His suggestion that the Legion might send a special delegation to visit the ex-Service organisations on the Continent now reads naïvely wishful with the benefit of hindsight.

In February 1939, a column appeared in The Times that outlines the British Legion’s annual report for the previous year, under the title ‘British Legion’s Work for Peace’. Despite claiming that 1938 ‘will be remembered for all time as the year in which the Legion put forth its greatest efforts towards the attainment of world peace’, the column concludes that 1938 ended with ‘grievous disappointments.’ The very same column also notes a ‘steady increase in the nation’s response to the Poppy Day appeal,’ a sign of the public’s ‘confidence reposed in the Legion and its work.’ In a strange turn of circumstances, the same organisation that introduced the most public displays of remembrance becomes itself a harbinger for the inevitability of another great war, and the penchant for memorialising reaches its heights just before the outbreak of a similar conflict.

Remembrance is bound to be reiterative. Remembrances are tempting occasions to consolidate a uniform picture of the past, to lump decades of history into the poppy we put in our button holes for a month of the year. The act of remembering, however, also begins in medias res. There isn’t anything that inherently differentiates the events we choose to remember from the continuous fabric of the past. Perhaps next time we revisit these monumental events, we should also spare a moment for the ‘in between bits’ – they might have just as much to tell us about our history.

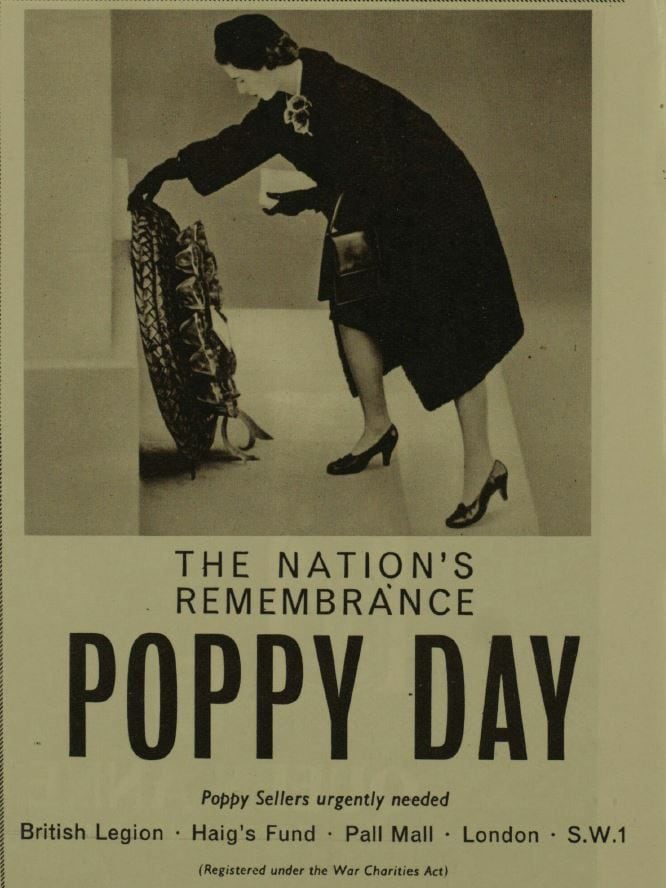

Blog post cover image citation: “Poppy Day.” 44th International Motor Exhibition Olympia (Supplement). Illustrated London News, 24 Oct. 1959, p. 524. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003, http://tinyurl.galegroup.com/tinyurl/8H7hg9. Accessed 6 Nov. 2018.