State Papers Online Eighteenth Century, Part IV: Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and Turkey is now available. The final part in the State Papers Online Eighteenth Century programme, Part IV rounds out the State Papers collection of 1714-1782 with series from Denmark, Sweden, Poland and Saxony, Prussia, Russia, Turkey and the Barbary States, as well as volumes of Treaties, papers sent to the British Secretaries of State from foreign ministers in England, and ‘confidential’ and intercepted letters between key figures in international politics. Joining the domestic, military, naval and registers of the Privy Council of Part I to the full scope of the State Papers Foreign offered in Parts II, III and IV, the State Papers Eighteenth Century collection represents the government of Britain at home and abroad in unequalled depth.

Including primary source material spanning decades from some of the most powerful courts in Europe, there is much to be discovered. With such a wealth of material available, where to begin? In this blog post I providea starting point, exploring just some of the highs and lows of Part IV for researchers, scholars and the perennially curious to explore.

Five coups d’état

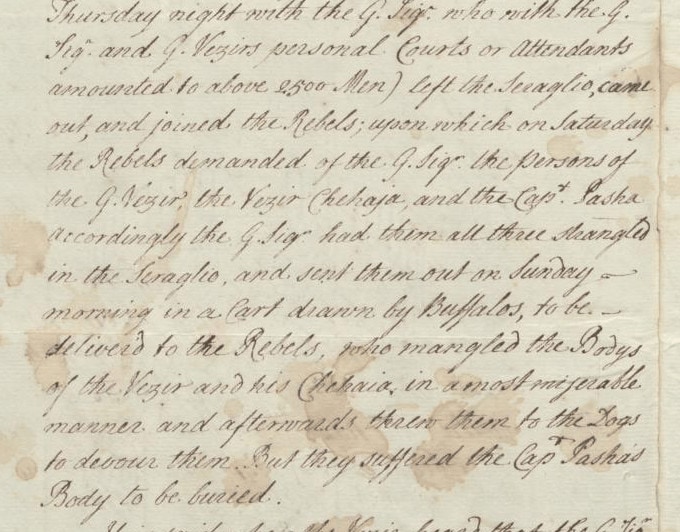

The eighteenth century was a precarious time to be in charge – between 1714 and 1782 there were coups in Poland, Russia, Sweden and the Sublime Porte (Ottoman Empire). The deposition of Ahmed III in 1730 in Constantinople was an old-fashioned, heads-at-the-city-gates style coup (see SP 97/26), while Gustav III of Sweden staged his own internal power grab while already king in 1772 (SP 95/121), wresting power back to the monarchy and ending the Swedish ‘Age of Liberty’. A previous attempt to do the same thing in 1756, masterminded by Louisa Ulrika, the wife of Adolf Frederick I, had failed (see SP 95/102).

But the honour of the highest turnover of royals in this period goes to Russia. Between 1714 and 1782 Russia had eight different monarchs: two were deposed and murdered; one died of smallpox on his wedding day, aged 14; and four reigned for less than five years. While Russia was not a popular destination for diplomats (as Edward Finch attested in 1741, writing ‘For God’s Sake, My Lord, let me get away, tho on my Return I was to be banished to the Orcades for Life, for here I cannot Live’ (SP 91/29 f.177)) they nevertheless found plenty to report. SP 91/29 covers the deposition of the fifteen-month-old Ivan VI in favour of Elizabeth, daughter of Peter the Great – impressively, not only was nobody killed during the coup, but Elizabeth never issued a death sentence during her reign. Ivan VI was imprisoned, and eventually killed by his guards in 1764. In 1762, Catherine the Great’s masterful seizure of power from her husband, Peter III, can be traced through SP 91/70.

Four Weddings

When they lived long enough to marry, European royalty engaged in dynastic marriages that were essential elements of international diplomacy. The Hanoverian Georgians particularly intermarried with the northern, Protestant dynasties that created valuable alliances for Hanover as well as Great Britain. George II married Caroline of Ansbach in 1705, whilst his sister Sophia Dorothea married the future Frederick William I of Prussia in 1706 and had fourteen children, including the future Frederick the Great. George II married his own children to various northern European rulers and nobles; within State Papers Eighteenth Century Part IV can be found details of the negotiations and ceremony surrounding the marriage of Princess Louisa of Great Britain to the future Frederick V of Denmark (SP 75/85), whilst the marriage of Anne, Princess Royal, to William IV, Prince of Orange, in 1734 is favourably received by the Russian court (see SP 91/14). The later wedding of George III’s sister, Caroline Matilda of Great Britain, and Christian VII of Denmark in 1766 ended in scandal and divorce in April 1772 (SP 75/125-162). Elsewhere, the marriage of Ulrika Eleanora of Sweden to the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel in March 1715 is described in SP 95/21, the beginning of Ulrika Eleanora relinquishing her royal power into the hands of her husband, in whose favour she would eventually abdicate in 1720.

Three Great Monarchs

Three of history’s ‘Greats’ appear in this segment of the State Papers – Peter I of Russia (r.1682-1725); Catherine II of Russia (r. 1762-1796); and Frederick II of Prussia (r. 1740-1786). Though not the longest reigning European monarchs of the eighteenth century (Louis XV reigned for 58 years, and George III was on the throne 60 years), the longevity of these three doubtless helped in their gaining the moniker ‘Great’. Contemporary perceptions of them as individuals and as rulers can be found in the reports of British ambassadors and envoys around Europe throughout their long reigns, covering the national politics, foreign policy and military machinations of these powerful figures. But things were not always easy…

Two Disgraced heirs

Frederick the Great appears in diplomatic correspondence long before he ascended to the Prussian throne; SP 90/29 from 1730 finds him caught up in a scandal that led to his disgrace and brief exile. The 18-year-old prince did not get on well with his father, and in 1730 attempted to flee Prussia for England with a group of friends, including Hans Hermann von Katte, a soldier in the Prussian army. The scheme was, however, betrayed to Frederick William I, and the conspirators were all arrested. They were accused of treason, and Frederick was made to witness the execution of von Katte. Frederick was himself pardoned, but stripped of his military rank and exiled from Berlin for two years. He was not, however, removed from the line of succession.

Less merciful was Peter the Great to his heir, Alexei Petrovich, in 1718. Alexei had already offered to renounce his claim in favour of his infant son (who would eventually rule as Peter II) when he fled Russia for Vienna and the protection of the emperor Charles VI. Humiliated, Peter the Great demanded his return; Alexei agreed on the condition that he was not to be punished. In fact, upon his return to Moscow an inquisition was set in motion that saw most of his friends arrested, Alexei renouncing the succession, his mother (banished to a monastery since 1698) tried for adultery, and many who had previously sympathised with or supported Alexei tortured and killed. Alexei himself was tortured and ultimately found guilty of treason. Sentenced to death, he died before the sentence was carried out. The aftermath of this episode is reported on in the State Papers’ correspondence long after Alexei’s death.

One Pirate

The grand sweep of history, the workings of government, and the personal lives of the rich and powerful are all here, but the State Papers also allow glimpses into the everyday details of life at the courts, and the characters and status of the people surrounding them. Russian ex-Boyars (the rank having been dissolved by Peter the Great), Prussian generals, and Swedish politicians all appear in these pages. And then there is the occasional more colourful character – a spy, the lover of a ruler, a charismatic power behind the throne. None, however, are more memorably terrifying or Game of Thrones-ready than the terrifying ‘Red Checks’. In Edward Finch’s own words from 1741:

‘The famous Krasno Tzockin, whose name in English signifies Red Checks, & whose Genius resembles that of the no less famous Black Beard the Pirate is lately come here. He has a Command among the Don Cossacks…& has the Rank of Brigadeer in the Russ Army. He is turned of Seventy, but has a great deal of desperate brutal Courage. He has knocked off several Score of his Prisoners’ Heads, sometimes in cold Blood, sometimes in drunken Fits, but always, as he says, to keep his Hand in: & has been wounded all over his Body; upon which occasions He only makes use of Human Fat by outward Applications, & inwardly also in a Glass of Brandy…He already declares, that the shortest way to destroy Game is by killing the Young ones, & his method is wherever he comes to put Women & Children to the Sword.’

Red Checks for the Iron Throne, anyone?