In the UK today, we associate fireworks with the fifth of November and (as the well-known nursery rhyme goes…) gunpowder, treason and plot. For many of us, fireworks are inextricably bound up with the smell of bonfire smoke, and standing in a park or sports ground, ankle deep in mud, waiting for the audio system to work. This is often combined with the unfettered glee of riding a fairground ride that appears never to have been safety tested! And of course, we all know and love the various fireworks themselves: the rockets, Roman Candles, Catherine Wheels, Golden Rain and sparklers. Perhaps your personal favourites are those that burst in gold, and then fizz silver? Maybe those that screech and scream? Or those that launch in a splendid spray of red and blue and then ‘phut’ into nothingness? Or the slow burner… refusing to go off until someone has cautiously poked it with a stick, whilst the others watch terrified that it should explode in the face of the poker… Firework night: a time of education and entertainment for all!

Many are unaware that fireworks were around long before Guy Fawkes got himself into a seditious predicament under the Houses of Parliament. Gunpowder, one of the ‘four great inventions’ of ancient China, was a revolutionary creation in the history of warfare (and therefore, the world). Indeed, fireworks in their current dramatic but rather more peaceful form, were not automatically seen as a means of entertainment. Fireworks as weaponry appear again and again in documents from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Gale Primary Sources, though they also appear in historical sources being used for less violent purposes.

For example, fireworks were used to tear down a bridge in Antwerp in 1585:

‘Antwerp, 1 May.—So far nothing is done against the bridge, but within a week the ships &c. will be ready in Holland, and here, besides the three already written of, they are making ready ten smaller ones, laden with fireworks, and another which will go under water, full of powder, iron and stones, to wreck the bridge and drive the Malcontents off the dyke’

A few years before this incident, an account of a celebration in Constantinople describes the splendid firework displays at the Hippodrome; ‘fireworks without end’, ‘such a quantity of fireworks that the air seemed to burn on all sides,’ during the festival of the Age of the Janissaries. Among the many fireworks used are mentioned a ‘mountain’, ‘castles’, ‘some models of men on horseback, but full of fireworks’ and a display by ‘two galleys as long as a gondola which fought together with fireworks for more than an hour…[and] gave the people the greatest pleasure’[1]

With the advent of print culture, firework displays appeared frequently in the pages of newspapers and books, perhaps paralleling an increase in public entertainments and the popularity of such events. In 1730, The Daily Post Boy, a paper in the Nichols Newspaper Collection, lists a mysterious array of fireworks, including the Rainbow, the Rising Sun and the Goddess Iris, among a variety of entertainments.

While they may have become more common, the grandeur and drama of firework displays only grew. The ‘General Peace’ after the War of the Austrian Succession was celebrated in London with a grand fireworks display in October of 1748, and it was reported on in detail.

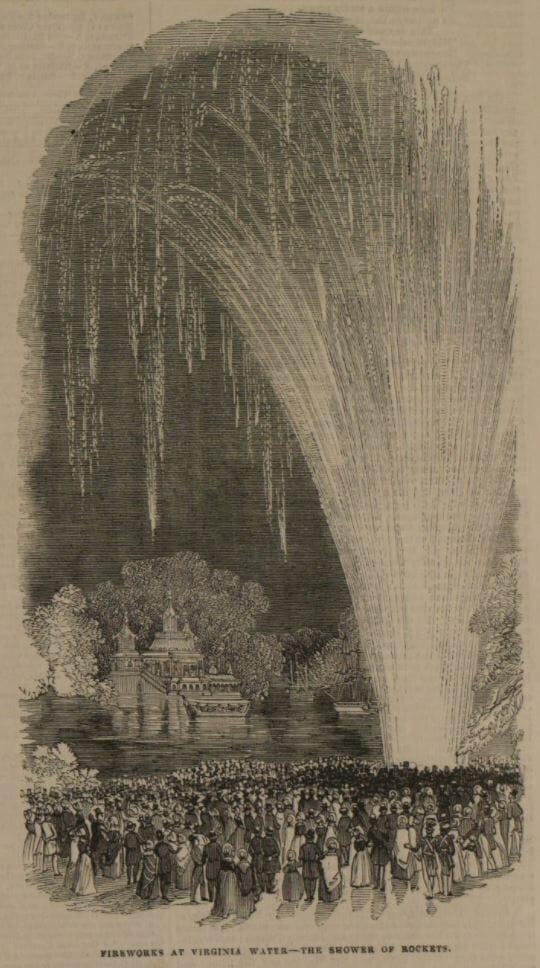

Firework displays were a frequent and popular part of Victorian entertainments as well – from Prince Albert’s birthday in 1843 in London, to Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee Celebrations in Penang in Malaysia, fireworks were a key part of the running order.

Drawings such as the above, from the Illustrated London News, are the best images we have of fireworks before photography was able to capture them in all their dazzling glory, although even with this new technology some images remained more impressive than others…..

By the end of the nineteenth century, fireworks as a domestic spectacle were being marketed, and the early advertisements in collections such as Nineteenth Century U.S. Newspapers and The Times Digital Archive can tell us much about who they were aimed at, and the occasions for which they were used. They can also shed some interesting light on attitudes to safety and childhood in the same era.

In the Daily Inter Ocean in Chicago in 1893, children were tempted with the full page spread of ‘Fireworks for Nothing!’, with its headline,

‘Why not be a really-and-truly American boy this year, and EARN YOUR OWN FIREWORKS, eh? Papa’s busy; mamma’s got baby’s summer clothes to make. Just think of the relief to them and the fun you’d have if you earned a big box of fireworks – all your very own – that they knew nothing about!’

After all, what could be better than fireworks in the hands of unsupervised children?!

[1] “Triumphs and shows of Grand Turk.” Jul. 21 1582. MS Secretaries of State: State Papers Foreign, Turkey, 1579-1779. SP 97/1 f.20. The National Archives of the UK. State Papers Online. Web. 1 Nov. 2017.

Document URL: http://go.galegroup.com/mss/i.do?&id=GALE%7CMC4321880007&v=2.1&u=webdemo&it=r&p=SPOL&sw=w&viewtype=Manuscript