Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙aka. 孫中山 or 孫文; 1866–1925) was a Chinese revolutionary and leader of a series of armed uprisings that led to the downfall of China’s last imperial dynasty (the Qing) in 1911 and the founding of the Republic of China in 1912. November 12 this year marked his 150th birthday.

Searching for his name (“Sun Yat-sen” or “Sun Wen”) in Gale’s China from Empire to Republic: Missionary, Sinology and Literary Periodicals – a unique collection of 17 English-language periodicals published in and about China – offers the researcher a significant quantity of material about this individual. Over two-thirds of the 300-plus search results are from The China Critic and Tienhsia Monthly – periodicals run by Chinese intellectuals. His activities and ideas also attracted the attention of Westerner- or missionary-established periodicals such as The Chinese Recorder, West China Missionary News, and The China Yearbook.

Sun’s name is often associated with the epochal revolution of 1911. China Mission Year Book (1912) provided a detailed account of the background and progress of the revolutionary movement that overthrew the Manchu Qing dynasty. The Year Book also carried the full translation of Sun’s oath and proclamation as the first provisional president of the newly formed Republic of China:

The revolution was not complete, however, as northern China was still under the control of General Yuan Shikai, who was supported by the imperial government. To achieve a united China, Sun offered Yuan the presidency on the condition that the Manchu emperor abdicated and Yuan supported the Republican government. On April 1, 1912, Sun relinquished his presidential title and duties, but what happened thereafter ran contrary to Sun’s hope because Yuan wanted to restore the imperial system by declaring himself emperor. To counter this, Sun and his Nationalist Party (Kuomintang) colleagues launched the Second Revolution to force Yuan to step down.

With Yuan’s death in June 1916, China plunged into a decade of social and political chaos, with revolutionaries and warlords fighting one another for the control of all, or part, of China. Never giving up his dream of building a united Chinese republic, Sun reformed his party and pushed for a nationalist-communist alliance. He went to Beijing in December 1924 to discuss a possible accord with Marshall Duan Qirui and Zhang Zuolin, two powerful warlords controlling northern China, but died of cancer on 12 March, 1925 in Beijing.

Sun left behind a very famous will, and a modified quotation from it – 革命尚未成功,同志仍须努力 / ‘As the Revolution has not yet come to a complete success, my compatriots must continue to strive’ – has become a household phrase in mainland China and Taiwan. The English translation was published in full in the Educational Review in January, 1927.

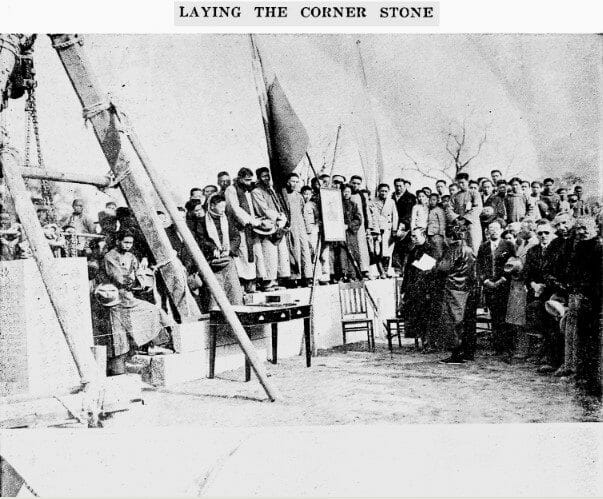

His will was so influential and inspiring that it was even read out to all the attendees, both Chinese and foreign, at a ceremony marking the laying of the corner stone of a new building on the campus of the Catholic University of Peking in December, 1930 by Mr. Chang Chi, President of the Board of Trustees.

Sun’s passing away spawned a series of memorial and scholarly writings that lasted till the 1930s. For instance, China Critic published two eulogies on Sun, as well as a fairly detailed biography:

In comparison, The Chinese Recorder seemed to be more interested in summarising Sun’s intellectual legacy and published several lengthy essays researching Sun’s teachings (1926; 10 pages) and principles (1927; 5 pages). One such essay is unique in that the author compared Sun’s three principles of the people (三民主義) with the teachings of Jesus, probably due to the fact that Sun was a baptised Christian.

Today, ninety-one years after Sun passed away, he is still widely revered and honoured in Chinese communities across the world in the form of memorial halls, parks, statues, and portraits.

Happy Birthday Dr. Sun Yat-sen!