The Daily Telegraph newspaper is known for its ‘high tone’ and has acquired a reputation for being ‘serious, popular and pioneering’ over the years. A sign of its status can be traced back to the Second World War, where its editor’s willingness to depart from convention ensured the newspaper’s critical involvement in the War’s outcome. For the newspaper did not simply stand back and report on events, although the work of first female war correspondent Clare Hollingworth should not be downplayed, but unwittingly engaged itself in the Allied cause.

In January 1942, The Telegraph’s editor Arthur Watson invited 25 unsuspecting people to his newspaper’s Fleet Street newsroom to complete a crossword challenge. Little did these select few know that their performances would be scrutinised by government officials.

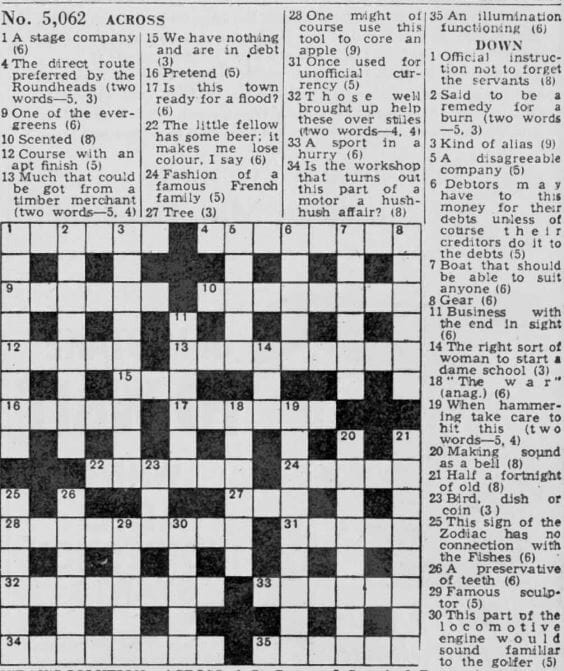

They had merely turned up in response to one man’s challenge that such puzzles could not be solved within twelve minutes. So they innocently worked their way through the cryptic teaser, which had been drawn out of a hat. Of the 25 participants, just five managed to complete the crossword within the twelve-minute deadline. The winner was an F. H. W. Hawes, who recorded an impressive (and very precise) time of seven minutes, 57.5 seconds. This select group was reduced to four though, when it emerged that one person had misspelt a word in their haste to complete the challenge. He was duly disqualified. Still, four people had defied the claim of a Mr Gavin that these crosswords could not be solved within twelve minutes; the £100 prize was donated to a ‘deserving Service fund’ as a result.

Of greater significance was the governmental interest in the four successful competitors. A few weeks after they had taken part, the War Office sent letters to these individuals regarding a ‘matter of national importance’. Their invite to meet with Colonel Nicholas of the General Staff led to their recruitment as Allied codebreakers, unlocking the complex codes of the famous ‘Enigma’ machine at Bletchley Park. Such was the fame of this story that it was recently the subject of the Academy Award-winning film The Imitation Game.

The newspaper itself was supposedly as unaware as its readers of the potential for government-level interest in its crossword. Yet it still drew considerable attention to it in the days that followed. On 12 January, the first edition published after the crossword ‘match’, it printed a picture of the competitors alongside an article (above). The next day, it printed two articles referencing the ‘Timeless Test’, enticing readers to have a go themselves at completing the task.

Whether or not it is the influence of hindsight, it is hard to believe that The Telegraph knew nothing of the War Office’s intent. The event was evidently deemed significant enough to warrant the inclusion of the above picture on 12 January – surely this would not have been necessary for an incidental competition?

The language, too, seems a little suspicious. Take the first line, for example, where it announces the crossword ‘to the world’. This seems a somewhat embellished way of introducing an innocuous daily puzzle. And then there’s the military terminology ‘coup d’oeil’ – a phrase associated with quickly assessing an opponent’s weaknesses. This is followed by clear attempts to play down its significance; further on it states that the puzzle ‘will need no other commendation this morning’. Not that morning, perhaps, but it certainly received plenty of attention over the following weeks. Was The Telegraph really completely in the dark over the War Office’s potential interest in the competition? It is a question which is likely to remain unanswered. But the air of mystery surrounding the whole episode is captivating; a historical parallel to GCHQ’s recent Christmas card brain-teaser.

Why not have a go yourself? The puzzle can be found within The Telegraph Historical Archive, 1855-2000. But be warned; no prize can be offered on this occasion, let alone governmental recruitment!

You can request an institutional trial of The Telegraph Historical Archive, 1855-2000 by emailing [email protected]