In August 1745, Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s Highland army embarked on its journey across Scotland, marking the onset of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. Determined to restore the Stuart monarchy to the throne, and severe the Union of 1707 which bound Scotland to Britain, the Prince led his Jacobite followers into battles across Scotland and the North of England. Replete with themes of individual heroism, and of the struggle of the few against the tyranny of the establishment, it is little wonder that the story of ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ has come to acquire mythical status. 270 years on from what was effectively the beginning of the end of the Jacobite cause, I couldn’t resist delving into some of the original documents from our State Papers Online: Eighteenth Century resource, which gives us some clues as to why the rising – and the figure at its head – has become so romanticised.

Letter from Charles Edward Stuart to the ‘nobility, gentry and free-born subjects’, 2 November 1745. SP 54/26 f.192

Take, for example, the Prince’s printed letter of November 1745, in which the Jacobite case is passionately put forward to the ‘nobility, gentry and free-born subjects’. The resolution of the ‘Young Pretender’ (as Charles Edward was also known) to present the sanctity of the Jacobite cause is striking. In contrast to their enemies’ depiction of them as ‘Men of low Birth’, the Jacobites are ‘of the most ancient Families of this Island’. Therefore, the Prince affirmed, they had ‘good blood’, helping to justify their call to arms in the name of God. On reading the letter, it is difficult not to be swept up in the emotion of such stirring rhetoric. Published in the midst of early Jacobite successes at Edinburgh and Prestonpans, the Prince’s heroic image would surely have gained considerable momentum.

Plan for the Battle of Prestonpans, 30 October 1745. SP54/26 f.107

It is not, though, merely acts of valour which have helped to entrench the story of Bonnie Prince Charlie. When looking at another gem from the State Papers series (and a personal favourite of mine), it is easy to see why the Prince has achieved such eminence.

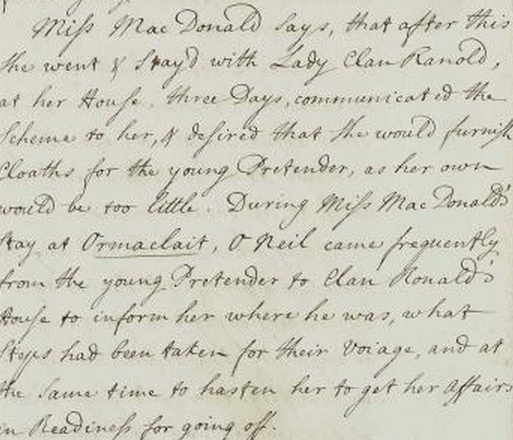

Contained within the papers of Scotland’s Secretaries of State is the statement of a Miss Flora MacDonald, who assisted Charles Edward’s escape to the island of Skye following the Jacobite defeat at Culloden. It is less the fact that the Prince fled, but the manner in which this happened which is most notable: crucial to his successful escape was the disguise he adopted. He dressed in ‘woman’s cloathes’ [sic], which had been specially sought by Miss MacDonald – her own, she explained, were ‘too little’.

Copy of the Declaration of Miss MacDonald, 12 July 1746. SP54/32 f.49e

Adorned in a woman’s cloak, with his face partly concealed by a hood, Prince Charles Edward Stuart, the mighty ‘Young Pretender’, thus effected his escape. Reading through the account, I couldn’t help but recall Toad of Toad Hall fleeing in his charming washerwoman’s attire in The Wind in the Willows.

The fantastically farcical nature of the episode stands at odds with the steely young leader depicted earlier; you can just imagine what contemporaries would have made of the effeminately-dressed Prince. The escape marked the final act of a quest characterised from the start by one man’s gung-ho individualism. It did not matter that his efforts were ultimately in vain; ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ had resolutely stood against the Hanoverian monarchy to embody the role of the underdog, cementing his status in the eyes of many as a devoted, if flawed, hero. Reconsidering these events helps to explain why the 1745 rising continues to resonate to this day.