On Wednesday night the BBC premiered Canal+’s lavish new period drama, Versailles. Always a sucker for period dramas, I looked forward to this one especially as I had no idea of the plot beforehand so the drama was a complete surprise, and I had very fond memories of a trip to the real Versailles as a student. Home of Louis XIV, the Sun King, Versailles was the seat of French government for most of the 18th Century, and if the TV show is to be believed, was the centre of much political intrigue.

State Papers

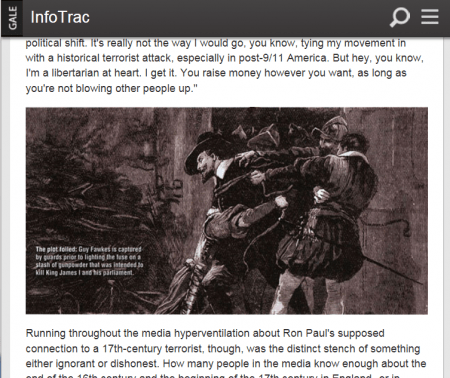

The Figure of Guy Fawkes – Past, Present and Future

Guy Fawkes has become something of an icon in the British psyche; we foster an underlying admiration for the plotter, despite his attempt to orchestrate murder. This is partly based on an innocent relish for royal intrigue and romanticised view of a time of ruffs, candles and pointed shoes. Yet there is a tension between British attitudes towards recent acts of social disorder, terrorism and violent political expression, and our euphemized view of attempted murder in seventeenth-century England. The complexity of our collective memorialisation and current attitude towards the Gunpowder Plot can be explored by charting its development in the Gale archives.

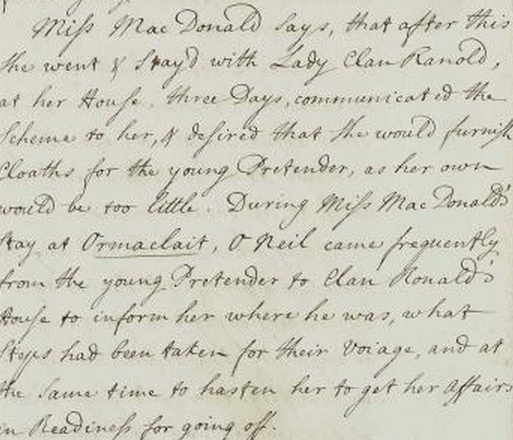

Bonnie Prince Charlie and ‘the ‘45’

In August 1745, Prince Charles Edward Stuart’s Highland army embarked on its journey across Scotland, marking the onset of the 1745 Jacobite Rising. Determined to restore the Stuart monarchy to the throne, and severe the Union of 1707 which bound Scotland to Britain, the Prince led his Jacobite followers into battles across Scotland and the North of England. Replete with themes of individual heroism, and of the struggle of the few against the tyranny of the establishment, it is little wonder that the story of ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ has come to acquire mythical status. 270 years on from what was effectively the beginning of the end of the Jacobite cause, I couldn’t resist delving into some of the original documents from our State Papers Online: Eighteenth Century resource, which gives us some clues as to why the rising – and the figure at its head – has become so romanticised.