│By Alison Foster, Gale Technical Support Executive│

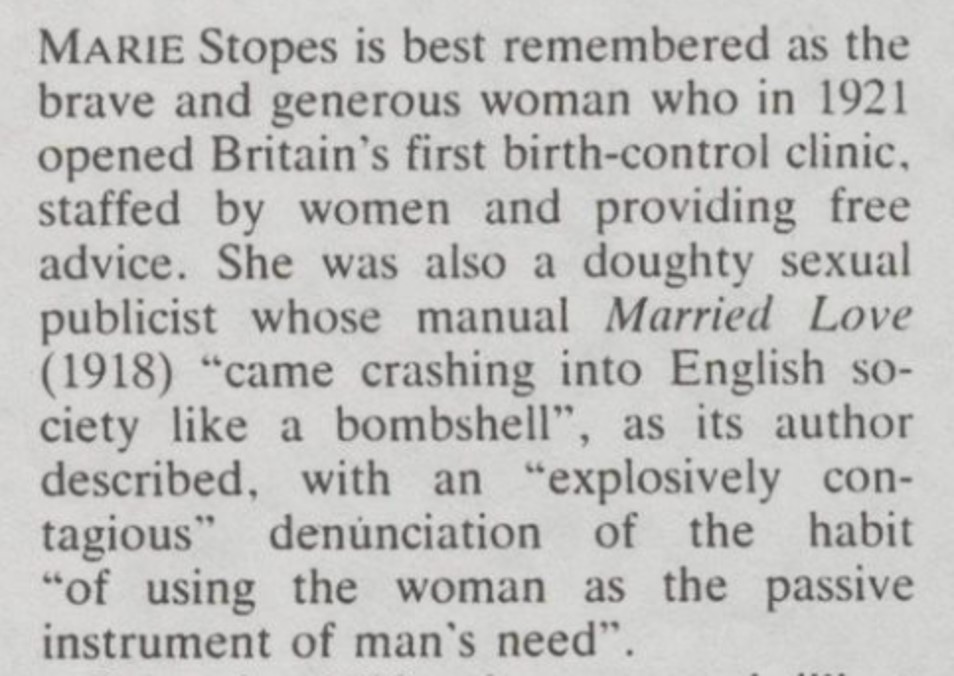

‘A magnificent monster,’ as described by Nature magazine in 1992, Marie Stopes (1880-1958) was markedly renown for successfully opening the first birth control clinic in the world, in London, in 1921. This, and subsequent clinics, gave free advice about reproductive health to married women without the sanction of the medical or health community.

Although a successful academic in her own right, it may appear that the most pivotal moment in Marie’s life was her annulment from her first husband around 1914. Marie complained that her husband was ignorant about sex and claimed that after three years their marriage was not consummated. Without consummation, this meant that they could apply for an annulment instead of a divorce, which was culturally frowned upon at the time.

At the turn of the twentieth century, there was no sex education in schools or at home, and many marriages struggled trying to navigate sexual intimacy in the midst of the relationship, as sex was strictly not permitted outside of marriage. This was compounded, of course, by individuals who did not identify as heterosexual.

Stopes Emerges in Her Second Career, and Second Marriage

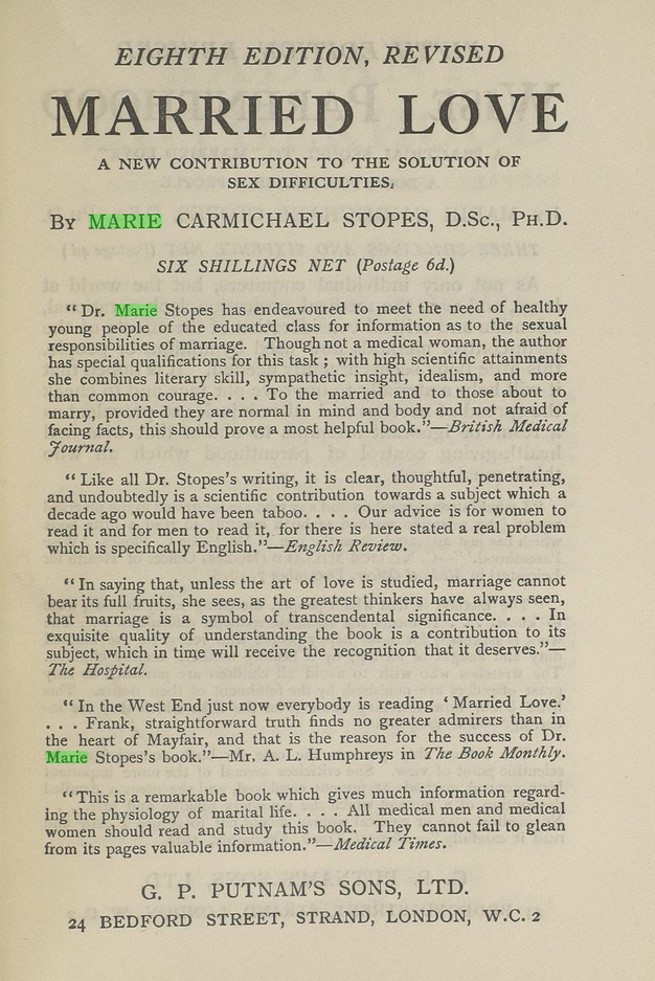

At the time English women were described as suffering from “the passive instrument of man’s need”, “excessive childbearing”, and high child mortality rates, Marie Stopes, unmarried and childless, leapt into public visibility as an author. Shortly after her marriage annulment, this was likely the impetus for Stopes to compose her first book in 1917, entitled Married Love: A New Contribution to The Solution Of Sex Difficulties.

She struggled to get it published, so a benefactor, Humphrey Roe, financed its publication in March, 1918. Two months later, Humphrey and Marie were married. When the book was finally published, it was quickly recognised to be a ‘sex manual’ and was banned in the USA. It launched into its sixth printing within a fortnight. Although disparaged in the UK, Stopes’ book went on to achieve nineteen editions and sales of almost 750,000 copies by 1931.

Reformers had been challenging Victorian ideas about sexuality and birth control since the 1870s, but few had as great of an impact as Stopes. Her first book was explicit about female anatomy, orgasm, and the function of sex.

Wise Parenthood

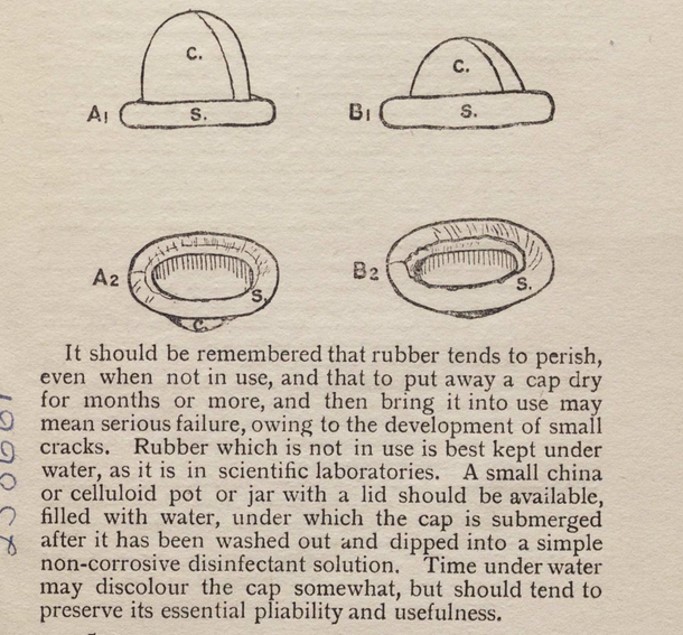

Stopes quickly followed up the success of Married Love by publishing her second book, Wise Parenthood: A Book for Married People, later that same year. This book was less about parenting children and more about how women can enjoy sex and avoid pregnancy. She went into even more depth specifically about birth control in this book, as described by this illustration of the rubber cervical cap below:

Wise Parenthood was printed into ten editions and a major triumph. The full texts of both books are available through Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender. With the success of these two works, Stopes began to receive a flood of letters “from those who wanted advice, those who supported her and those who were against her” and such letters were said to “highlight the frequent cruelty of the medical profession in dealing with women’s problems”.

![Advert for Radiant Motherhood in The control of parenthood: by J. Arthur Thomson [and others] Ed. by James Marchant](https://review.gale.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Picture10.jpg)

As an author, Marie Stopes went on to publish another thirteen books about sex, passion, venereal disease, and contraception. In 1920, she wrote Radiant Motherhood: A Book for Those Who are Creating the Future, despite the fact that she was not a mother herself.

Planned Reproduction

The clinic that Stopes opened in 1921 was in a poor neighbourhood and likely didn’t serve her upper-middle class friends. Eugenicists in Marie Stopes’ era were in favour of adjusting the human gene pool by excluding people that were considered as inferior. These were not only Nazi ideas. They were extremely popular ideas globally, and especially in England, the USA, and Australia. Forced sterilisation was practiced in the USA into the 1970s.

There appears to be a significant connection between ‘family planning’ and ‘planned reproduction,’ or population control. Stopes was a member of the Social Purity Movement and Eugenics Society. Language has changed much over a short period of time, and blatant racism and its affiliated terms go largely unmentioned in most writing of the period, which makes it difficult to research historically. Stopes’ rubber diaphragm was named ‘the racial cap,’ and in 1934 she wrote a book about it: Racial Occlusive Cap: Instructions How to Use the Racial Cap.

Pregnancy and Motherhood

Stopes wrote Radiant Motherhood when she had one pregnancy lost at birth in the year prior. The final chapters of that book are mostly on the subject of Eugenics. She fell pregnant only four months into her second marriage when she had cautioned married couples to delay conceiving after marriage ‘to secure the lasting happiness of the married lovers’ in her book, Married Love, only two years earlier.

In 1919, presumably while pregnant, Stopes published a free pamphlet: A Letter to Working Mothers on How to Have Healthy Children and Avoid Weakening Pregnancies. About four years later, she finally bore one son when she was 43 (a very late age to begin childbearing at the time). His name was Harry.

If you have any doubts about Stopes’ intentions, and her commitment to the cause, her only son Harry became a successful humanist and philosopher. Stopes refused to attend his wedding. He married a short-sighted woman, a genetic defect, and so Stopes thought her grandchildren might inherit the condition. As a result, she bequeathed him thirteen volumes of the Greater Oxford English Dictionary and a cottage. She left all her clinics and greater inheritance to the Eugenics Society.

Popularity and The Second Sexual Revolution

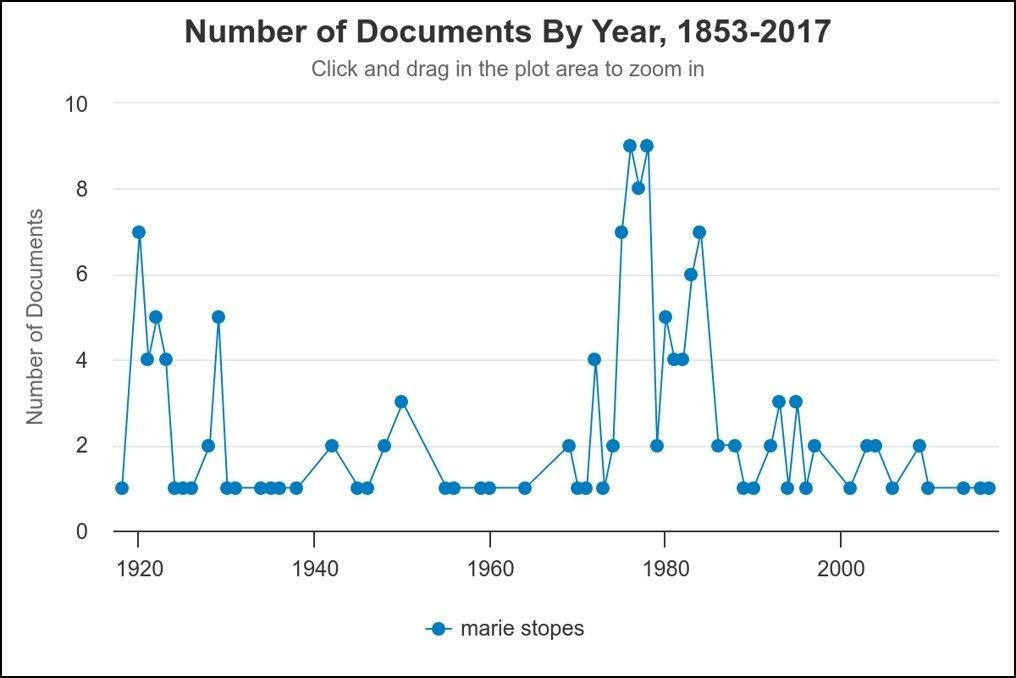

A small glimpse into the cultural context and her personal life gives a greater framework to Marie Stopes’ work. A term frequency search for Marie Stopes in Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender shows that although her name found celebrity with her early publications, she rose to greater prominence in the 1970s and 80s as she was cited throughout this second sexual revolution and the path towards women’s liberation.

You can find Marie Stopes’ books, her biography in articles, clinic correspondence, field officer schedule of commitments, papers, family planning leaflets, annual reports, and newsletters of her organisations/clinics in Gale’s Archives of Sexuality and Gender. For further study: search the archives for population control at the turn of the twentieth century or read more about Stopes in Women’s Studies Archives.

If you enjoyed reading about Marie Stopes and family planning, check out these blog posts:

- Early Modern Medicine: Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health

- How Gale’s Archives Supported My Thesis on the Politics of Contraception in South Africa, 1970s-80s

- Birth Control: A History in Women’s Voices

Blog post cover image citation: Marie Stopes International Australia. “Marie Stopes at her laboratory in the Victoria University of Manchester, studying ‘what appear to be coal ball slides’”. Wikimedia Commons. 1904. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Marie_Stopes_in_her_laboratory,_1904_-_Restoration.jpg.